![]() If you value this content, please engage in reciprocity by living, sharing and giving.

If you value this content, please engage in reciprocity by living, sharing and giving.

All posts by Valerie Ringland

Big news!

Vlog by Lukas

![]() If you value this content, please engage in reciprocity by living, sharing and giving.

If you value this content, please engage in reciprocity by living, sharing and giving.

On Gossip

I tend to err on the side of sharing things that feel like warnings about concerning behaviours or values conflicts. I also share things I find especially hard to witness and want help with when I feel that others might be able to hold the story with compassion or offer me insight. I see many people who are averse to gossip both titillated with taboo interest in it as well as acting nervous. Interestingly, people who lean into caring gossip sharing I find tend to be less judgemental than those who shy away. It’s as if those who avoid it are scared of being judged so they want to protect themselves and others from that, even at the expense of improving protection. (I say caring gossip sharing because intention matters, and it feels different than spreading rumours or not letting someone live down one poor decision.) (Image from here)

I tend to err on the side of sharing things that feel like warnings about concerning behaviours or values conflicts. I also share things I find especially hard to witness and want help with when I feel that others might be able to hold the story with compassion or offer me insight. I see many people who are averse to gossip both titillated with taboo interest in it as well as acting nervous. Interestingly, people who lean into caring gossip sharing I find tend to be less judgemental than those who shy away. It’s as if those who avoid it are scared of being judged so they want to protect themselves and others from that, even at the expense of improving protection. (I say caring gossip sharing because intention matters, and it feels different than spreading rumours or not letting someone live down one poor decision.) (Image from here)Sacred Communication Dialogue

![]() If you value this content, please engage in reciprocity by living, sharing and giving.

If you value this content, please engage in reciprocity by living, sharing and giving.

Vlog 1 – Winter Solstice

![]() If you value this content, please engage in reciprocity by living, sharing and giving.

If you value this content, please engage in reciprocity by living, sharing and giving.

Book Announcement

Valerie’s book-baby is about to be published/born, on July 24 (Australia & New Zealand) & August 24 (US, Europe, Canada, Singapore, & other English-speaking countries).

The front & back cover from the official Rockpool & Simon & Schuster pages:

Available in many bookstores, hopefully your favourite one! A big thank you for pre-ordering & spreading the word to others who may be interested.

Honouring lack

Is it worth decolonizing my Filipino spirituality and mentality?

Blog by Ellis Bien Ilas

“The Filipinos of today are the happiest people I know. Why revisit the past and why does it matter now?” She told me with an unsure smile. I only just met her for the first time five minutes ago and somehow, our conversation took an unexpected dip into the stories rarely told territory.

When two strangers realise they’re both Pinoys because curiosity has prompted either of them to ask “Are you Filipino?”, there’s typically a surge of excitement when it’s a match. Usually, I reply by either talking about how long since I’ve been back in the Philippines or how much fun I had in my most recent trip. In this case, I had just returned from a trip to my homeland after a 5 year drought.

I casually recounted that while my trip was short and sweet, I was also on a mission to discover some local books on Filipino History. A quest that took me at least 9 book stores until a kind soul directed me to a shelf filled of said books on the second last day of my trip. It was a welcome relief after being repeatedly directed to the Filipino cookbooks section in my prior search.

Back to our unplanned discourse, I couldn’t possibly not share a tidbit or two about how aghast I was at what I’ve learned so far. Especially how our distant relatives have been wrecklessly jostled about from the Spanish to the Americans in deeply degrading (and staged) circumstances.

“…why does it matter now?” she recoiled back.

The sound of my name being called broke my reverie as I mulled her question. I was in an animal shelter and fortunately, it was my time in the queue to be attended to.

Being a Filipino-Australian who has been living in Australia since I was eight years old, I have also felt a gnawing inkling that now would be a great time in my life to rediscover my Filipino roots.

How does one start though? Scholarly articles and the very limited Filipino history ebooks on Amazon points to the fact that the colonial legacy of the Philippine’s past has left deep scars in the Filipino psyche, including “internalised oppression, self-hatred and colonial mentality” (David & Okazaki, 2006).

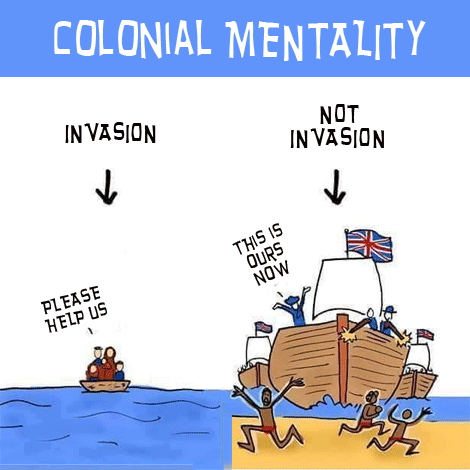

Hang on. Colonial Mentality? What does that actually mean?

Colonial Mentality

According to Nadal et al. (2016), colonial mentality refers to the internalisation of colonial values, beliefs and practices that devalue Filipino culture, language and identity. This can manifest as embarassment or feelings of inferiority over Filipino tradition and practices.

According to Nadal et al. (2016), colonial mentality refers to the internalisation of colonial values, beliefs and practices that devalue Filipino culture, language and identity. This can manifest as embarassment or feelings of inferiority over Filipino tradition and practices.

I recall when I first moved here in Sydney, Australia on several occassions, how several of my Filipino peers more often than not, proclaimed they were Fillipino-Spanish (even if that was 1/32th in bloodline). (Image from here)

“It just makes me sound more interesting you know. I’m not just another flip (Inner West Sydney slang for Filipino back in that time) who’s also a fob (fresh off the boat)”, I vividly recall an acquaintance disclosing.

David and Okazaki (2006, p.335) defines colonial mentality as “the conscious or unconscious acceptance of the belief that traits, values and practices associated with the coloniser are inherently superior to those associated with the colonised”.

To dive a little deeper, the authors developed the Colonial Mentality Scale to measure colonial mentality, which includes the following dimensions:

1. Belief in the superiority of Western physical features (e.g., light skin, straight hair)

2. Belief in the superiority of Western cultural values (e.g., individualism, direct communication)

3. Belief in the superiority of Western education and credentials

4. Belief in the superiority of Western technology and innovation

5. Belief in the superiority of Western religion and morality

The authors found that colonial mentality was significantly associated with lower self-esteem, higher acculturative stress, and lower levels of Filipino cultural values and practices among Filipino Americans.

So basically, colonial mentality has negative consequences for our mental health and well-being.

Decolonizing the Filipino Spirituality

Mention the word spirit or espiritu to a Filipino and you’ll either be discussing about perceived ghost sightings/apparitions (which stems from one of the Philippines’ pre-colonial belief systems referred to as animism — the belief that objects, places or creatures all possess a distinct spiritual essence) or, you’d be discussing the divine power of the Holy Spirit (through the lens of the Romantic Catholic faith).

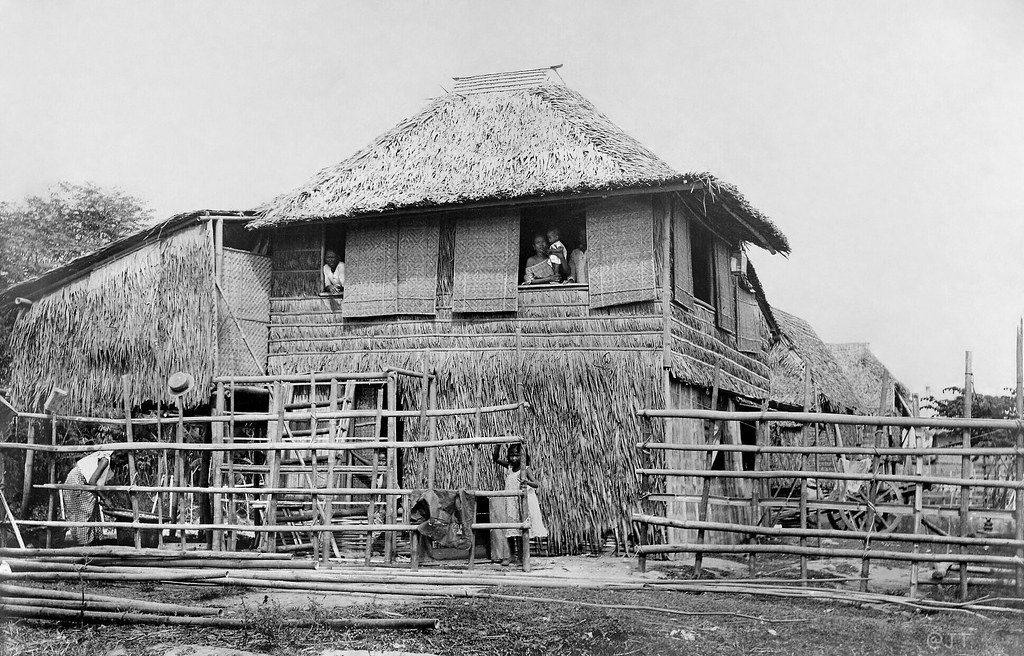

Constantino (1975) argued that Spanish colonialism and Catholicism had a profound impact on the Philippines, including the suppression of indigenous spirituality and cultural practices (which were largely based on animism), leading to the creation of a colonial and clerical elite. It also strongly impacted Filipino values and beliefs, how Filipino society is organised and the perpetuation of patriarchal and authoritarian structures of power, gender inequality and resistance to social and political change. (Image of pre-colonial Philippines house from here)

Constantino (1975) argued that Spanish colonialism and Catholicism had a profound impact on the Philippines, including the suppression of indigenous spirituality and cultural practices (which were largely based on animism), leading to the creation of a colonial and clerical elite. It also strongly impacted Filipino values and beliefs, how Filipino society is organised and the perpetuation of patriarchal and authoritarian structures of power, gender inequality and resistance to social and political change. (Image of pre-colonial Philippines house from here)

Let’s look at the typical Filipino family unit. Respecting and obeying Filipino parents and elders are deeply ingrained value and practice that is often associated with the way Catholicism has spread in the Philippines. These values and practices are based on the belief that Filipino parents and elders have the ultimate authority and control over their children and younger family members, and that their decisions and actions should not be questioned or challenged.

However, this value and practice can also perpetuate toxic and abusive dynamics in the Filipino family unit, particularly in relation to the reinforcement of authoritarian structures of power. For example, Filipino parents and elders may use their authority and control to enforce strict and oppressive rules and expectations, such as the control of their children’s education, career, and relationships; the restriction of their freedom and autonomy and the perpetuation of gender stereotypes and roles.

These dynamics can lead to unknowingly abusing that power, such as the emotional, physical, and sexual abuse of children and younger family members; the neglect and marginalization of their needs and rights, and the undermining of their agency and participation.

In light of the above, I’m not saying that Catholicism was all doom and gloom. I acknowledge that it also helped develop the Philippines through education and healthcare, as well as a sense of community and solidarity (which appears to still hold strongly today). However, it has caused issues still pervasive today. Problems that manifest in everyday life and I would imagine, most Filipino family units. Problems that I’ve seen myself and maybe, you have too. It’s possible that you have also considered, in the grand scheme of things, how did we get here and what can I do about it?

So… is it worth decolonizing my Filipino spirituality and mentality?

Considering the complex, multifaceted and evolving nature of the process of decolonisation, I don’t think I can reach a point and say, yeah, I’ve become decolonized now. Far from it.

But I am interested in improving my mental health and well-being, and this aspect of decolinization is a part of that process.

Despite this being in the making in the past few years, I’ve really only just taken my first few steps. My goal is to share this ever-evolving journey with others who may have had this spark lit within them. I’m curious to hear from you.

References

Constantino, R., & Constantino, L. R. (1975). The Philippines: A past revisited (Vol. 1). Quezon City: Renato Constantino.

David, E. J. R., & Okazaki, S. (2006). Colonial mentality: a review and recommendation for Filipino American psychology. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 12(1), 1.

Nadal, K. L. (2020). Filipino American psychology: A handbook of theory, research, and clinical practice. John Wiley & Sons.

![]() If you value this content, please engage in reciprocity by living, sharing and giving.

If you value this content, please engage in reciprocity by living, sharing and giving.

Navigating Existential Judgment

Blog by Valerie

Lately some protracted conflicts have come to the surface in my life at a macro level in the world, and at a micro level in my daily life. I have been praying quite a lot since the war in Ukraine broke out, where my Jewish-Sumerian ancestors spent many generations living, and more recently about the war in the Middle East. It seems to me like there is existential war and rejection going on based in judgment, where one or more parties to a conflict feel they are fighting to exist in the minds and hearts of the other.

I find existential judgement incredibly dangerous and damaging and see it as the root of genocide. It feels to me like a hand rejecting its own finger. If we believe in a Creator with wisdom our human minds cannot comprehend, how can we put ourselves in the position of judging what the Creator brought into being? And to say another is allowed to exist elsewhere (NIMBY) is still judgmental, for if we force another to leave their home and live on different lands, we change their and our identities by disconnecting people from their earthly homes and playing the roles of victims and offenders.

On a micro level I’m seeing this thinking play out in some righteous social justice warrior crusades around me. I find the concept of ‘rights’ to be violent, though it has obvious practical value to create baseline standards for society. If we didn’t existentially judge certain struggles and behaviours as deeming people unworthy of housing or health care or food, then rights would simply represent social baselines we collectively agreed upon as minimum standards of care for all of us humans living here. But if a single mother can’t afford housing, or a man with mental illness isn’t at retirement age but can’t hold down a job, we don’t collectively agree how (or sometimes even if) to support their survival. Rights then get used in a forceful way to push a majority social group’s minimum standard of support onto the collective, and thus they often need to be en-forced. And when we are judged and caught up in the rights battles we feel, rightly so, like we are fighting for our survival. (See survival strategies blog)

I agree with Jungian scientist Fred Gustafson that the Western mind is “having a massive collective nervous breakdown” and is going to “war to determine whose anthropocentric [world]view is most valid [while] the earth and all its inhabitants [] suffer.”[1] I have not found sufficient solace for survival in the Western world alone.

For me it has been vital to live in two worlds: (1) a social reality that is based on a Western worldview, and (2) an earth-based reality based on an Indigenous worldview. When I’m caught up in a survival struggle in the Western world that’s terrifyingly real, and I’m feeling rejected and judged and shamed and angry, I can spiritually connect with the knowing from the Land and my ancestors that I’m not only allowed to exist but that I am wanted. This powerful medicine is all I have found that alleviates my existential wounds. Without it I feel like I would not still be here on this Earth, as my roots would have rotted and not been able to hold up the rest of my inner tree of life. (Image from here)

For me it has been vital to live in two worlds: (1) a social reality that is based on a Western worldview, and (2) an earth-based reality based on an Indigenous worldview. When I’m caught up in a survival struggle in the Western world that’s terrifyingly real, and I’m feeling rejected and judged and shamed and angry, I can spiritually connect with the knowing from the Land and my ancestors that I’m not only allowed to exist but that I am wanted. This powerful medicine is all I have found that alleviates my existential wounds. Without it I feel like I would not still be here on this Earth, as my roots would have rotted and not been able to hold up the rest of my inner tree of life. (Image from here)

If you’re also feeling some pain and heaviness about existential judgement and its impact, here are a few things that help me keep my spirits strong:

- Grieving is a way I like to express angry energy to avoid getting overwhelmed by righteousness and gain clarity which fights, if any, feel right for me to engage in, and what that means practically. You may prefer to yell and scream or throw things or punch a bag instead, so however you express anger to avoid it overwhelming you is helpful.

- Connecting with the land and ancestors where I am offers me powerful healing. I may give offerings as simple as feeding a bird or picking up rubbish, or as profound as a placenta burial or smoking/smudging ceremony. I may also cultivate a sit spot on the land, walk barefoot, and tend a tree altar. There are so many more ways to connect with the land where you live, these are but a few. The reverence we bring to the action we choose matters more, I think, than exactly what we do.

- Letting go of black-and-white, objective, judgmental thinking is something I am very fierce with myself about. Humility is an important value to me, so I ensure that even when I feel certain or highly confident about something that I carry a little bit of doubt. For example, I feel highly confident that child sex abuse (link) is a damaging act that is wrong to do. Yet my intense journey of seeking to heal that wound has brought me so much wisdom and peace. Spiritual gifts often thrive in grey, paradoxical spaces.

Altering my consciousness is another survival tool I use daily, primarily through embodied meditations and drum journeys. I do it to heal trauma, connect with ancestors and other spiritual guidance, and seek tools for every day survival such as deeper spaces of compassion or peace. However you are able to sink deeper than your everyday ‘known’ and familiar thought loops can bring you some healing. I do find, however, that embodied practices (such as using sound or dance or breath techniques) are more powerful than mind-based practices (such as meditating through your third eye or simply watching your thoughts).

Altering my consciousness is another survival tool I use daily, primarily through embodied meditations and drum journeys. I do it to heal trauma, connect with ancestors and other spiritual guidance, and seek tools for every day survival such as deeper spaces of compassion or peace. However you are able to sink deeper than your everyday ‘known’ and familiar thought loops can bring you some healing. I do find, however, that embodied practices (such as using sound or dance or breath techniques) are more powerful than mind-based practices (such as meditating through your third eye or simply watching your thoughts).

Thank you for reading this, and may your life be enriched (and even saved) by living in both worlds, as mine is.

[1] Gustafson, F. (1997). Dancing between two worlds: Jung and the Native American soul. Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press.

![]() If you value this content, please engage in reciprocity by living, sharing and giving.

If you value this content, please engage in reciprocity by living, sharing and giving.

Tattoos & Tradition

Blog by Valerie

This blog idea came to me a while ago when I read an article about the revival of Deq, a traditional tattooing technique in Kurdish and some other Arabic and Northern African cultures. I had always been told you can’t be buried in a Jewish cemetery with a tattoo, and something about this tradition resonated as more ancient and true to my Sumerian roots. The article explained that Deq is a form of worship, with tattooing the skin believed to also engrave a person’s soul. It is a women’s tradition that uses breast milk and another substance (such as soot) to create the ink. (Image from Wikipedia)

Deq differs greatly from modern conceptions of tattooing. While today individuals often get tattoos for decoration or to memorialise events, people, or beliefs, deq is traditionally done to request abundance, protection, blessings, or fertility from God.

Spiritual protection is a common reason for tattooing in Indigenous science. According to Western scientist Lars Krutak of the Smithsonian, traditional cultural tattooing is done for the following reasons:

- Adornment

- Identity

- Social status

- Therapeutic/Health

- Spiritual protection/Animal mimicry

(Krutak, L. (2015). The cultural heritage of tattooing: a brief history. In Tattooed skin and health (Vol. 48, pp. 1-5). Karger Publishers.) Most of these we can relate to today, though you may be wondering what therapeutic or health tattoos are. Among our ancient ancestors are tattooed ceramic figures that are over 6000 years old found in modern day Ukraine and Romania, and a 5000 year old mummy found preserved in ice in the Italian Alps who appears to have therapeutic tattoos in places on his body that look similar to a practice in traditional Asian cultural medicines. Such tattoos tend to be at joints and in the lower back. Tattooed mummies have also been found from Egypt to Siberia to Peru, and tattooed earthenwares of human or spirit figures have been found across the world from ancient Mississippi to Japan to the Philippines.

modern day Ukraine and Romania, and a 5000 year old mummy found preserved in ice in the Italian Alps who appears to have therapeutic tattoos in places on his body that look similar to a practice in traditional Asian cultural medicines. Such tattoos tend to be at joints and in the lower back. Tattooed mummies have also been found from Egypt to Siberia to Peru, and tattooed earthenwares of human or spirit figures have been found across the world from ancient Mississippi to Japan to the Philippines.

The word ‘tattoo’ was brought into English from James Cook’s 1770s journey to New Zealand and Tahiti, and supposedly inspired Western sailors to start a tradition of tattooing themselves to remember where they had traveled and people they missed at home. (Image of a Ta`avaha (headdress) with tattoos, Marquesas Islands, 1800s, via Te Papa from here) Though modern Polynesian tattoos differ by island and culture, generally tattoos are seen as a form of spiritual protection, cultural status symbols displaying rites of passage, and signifiers of ancestral lineage. Where tattoos are on the body, and what symbols and motifs are used, are also important as they link people to their Creation story:

The word ‘tattoo’ was brought into English from James Cook’s 1770s journey to New Zealand and Tahiti, and supposedly inspired Western sailors to start a tradition of tattooing themselves to remember where they had traveled and people they missed at home. (Image of a Ta`avaha (headdress) with tattoos, Marquesas Islands, 1800s, via Te Papa from here) Though modern Polynesian tattoos differ by island and culture, generally tattoos are seen as a form of spiritual protection, cultural status symbols displaying rites of passage, and signifiers of ancestral lineage. Where tattoos are on the body, and what symbols and motifs are used, are also important as they link people to their Creation story:

In Polynesian Mythology, the human body is linked to the two parents of humanity, Rangi (Heaven) and Papa (Earth). It was man’s quest to reunify these forces and one way was through tattooing. The body’s upper portion is often linked to Rangi, while the lower part is attached to Papa.

But tattoos have a long reputation as being lower class in Western culture due to their link with slavery and criminality, which can be traced back at least to ancient Greece and Rome, and likely to ancient Mesopotamia before then. As recently as in the 1800s in parts of Europe tattoos were being outlawed and seen as unChristian. And while the major world religions are not associated with traditional tattooing, there are exceptions, such as a Buddhist monastery in Thailand that “anchors” people into scripture with tattoos. (Image from here of Angelina Jolie). And while I can’t speak for how locals feel about Angelina’s tattoos (she was given Cambodian citizenship and adopted a child there, so she has come cultural connections), I feel uncomfortable about the amount of cultural appropriation that goes along with tattooing in

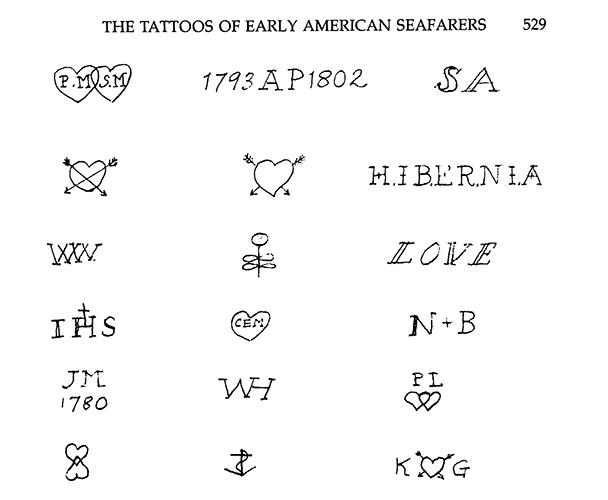

And while I can’t speak for how locals feel about Angelina’s tattoos (she was given Cambodian citizenship and adopted a child there, so she has come cultural connections), I feel uncomfortable about the amount of cultural appropriation that goes along with tattooing in  Western culture. I remember a trend some years ago of getting Chinese characters tattooed without many people even knowing or speaking the language. (I used to wonder how people weren’t scared they were lied to about what their tattoo said!) And many modern designs in Western culture have originated from those early sailors’ tattoos in the 1700s and 1800s. However, many have not, and where some celebrities like Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson express Samoan heritage through tattoos, others like Mike Tyson who is not of Maori descent has a ta moko design on his face (See this article on a history of tattooing in the U.S. by Sara Etherton). (Image from Visual log of tattoos seen on sailors in a survey done in 1809. (Ira Dye, “The Tattoos of Early American Seafarers, 1796-1818,” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 133, no. 4 [1989]: 520-554. accessed here).

Western culture. I remember a trend some years ago of getting Chinese characters tattooed without many people even knowing or speaking the language. (I used to wonder how people weren’t scared they were lied to about what their tattoo said!) And many modern designs in Western culture have originated from those early sailors’ tattoos in the 1700s and 1800s. However, many have not, and where some celebrities like Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson express Samoan heritage through tattoos, others like Mike Tyson who is not of Maori descent has a ta moko design on his face (See this article on a history of tattooing in the U.S. by Sara Etherton). (Image from Visual log of tattoos seen on sailors in a survey done in 1809. (Ira Dye, “The Tattoos of Early American Seafarers, 1796-1818,” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 133, no. 4 [1989]: 520-554. accessed here).

I have two tattoos. The first commemorates a flower I have a cultural connection with as well as a number, a colour, and some simples values; the second commemorates an insect I have a cultural and personal connection with. I got them both with close friends at the time during important moments in my life to mark endings/beginnings. Their placement is interesting – one on my right hip, and one on my left foot. I trust the intuition of those choices. I don’t notice them much anymore, they just feel like part of the fabric of me, and I’m thankful that though I got them when I was young, I still appreciate their presence on my body, and I have no need to be buried in a Jewish cemetery anyway.

Exercise: Reflect on any tattoos you have (or have considered getting). How do you feel about them – their aesthetic, meaning, and history? Is there anywhere you would or would not get a tattoo? Do you resonate with the idea that they connect you with your Creator or that they imprint onto your soul?

![]() If you value this content, please engage in reciprocity by living, sharing and giving.

If you value this content, please engage in reciprocity by living, sharing and giving.