![]() If you value this content, please engage in reciprocity by living, sharing and giving.

If you value this content, please engage in reciprocity by living, sharing and giving.

Category Archives: Indigenous Science

Upcoming Events – Austin & Waco

Come & join us in Texas!

Austin, Texas, USA – 7pm Wednesday October 9 @ BookWoman

Austin, Texas, USA – 2pm Saturday October 12 @ EyeoftheHeart

Texas, USA – 2pm Sunday October 13 @ ProvidenciaWaco

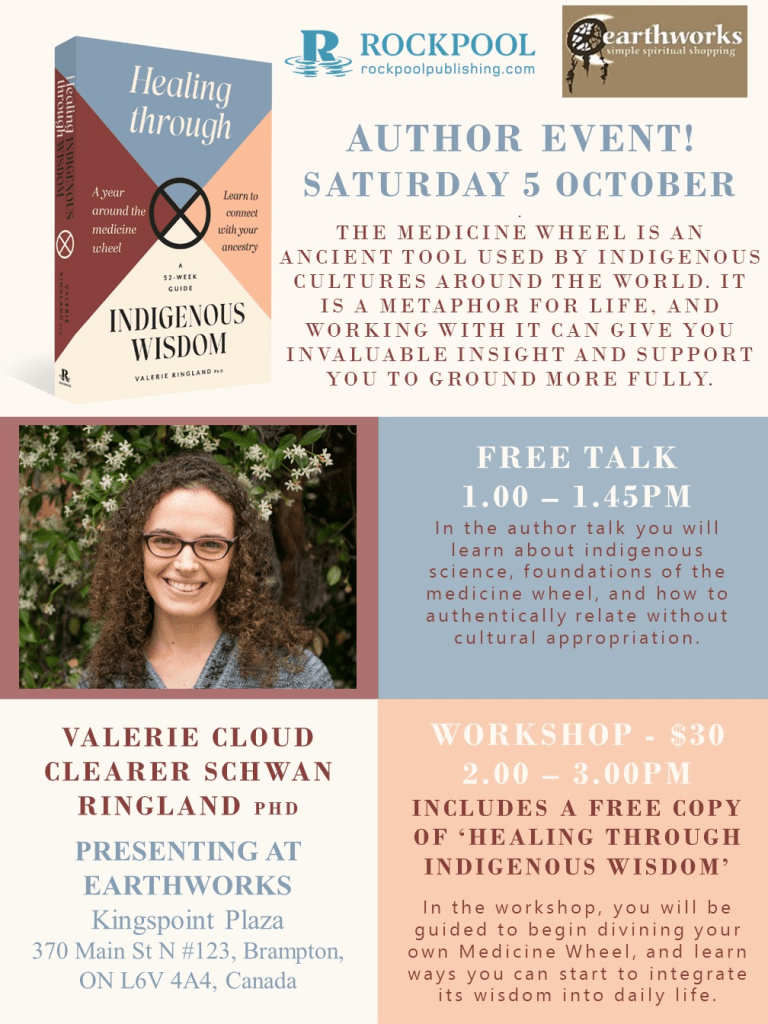

Upcoming Events – Toronto

Please join & pass it on! Find more events listed here in Austin & Sydney!

Toronto, CA – 1pm Saturday October 5 @ earthworks

Toronto, Canada – 2pm Sunday October 6 @ The Rock Store

Indigenous Ancestral Healing Workshop

Vlog 3: Dharraani Peace Centre is Born

![]() If you value this content, please engage in reciprocity by living, sharing and giving.

If you value this content, please engage in reciprocity by living, sharing and giving.

Living Systems Dialogue

![]() If you value this content, please engage in reciprocity by living, sharing and giving.

If you value this content, please engage in reciprocity by living, sharing and giving.

Big news!

Vlog by Lukas

![]() If you value this content, please engage in reciprocity by living, sharing and giving.

If you value this content, please engage in reciprocity by living, sharing and giving.

Book Announcement

Valerie’s book-baby is about to be published/born, on July 24 (Australia & New Zealand) & August 24 (US, Europe, Canada, Singapore, & other English-speaking countries).

The front & back cover from the official Rockpool & Simon & Schuster pages:

Available in many bookstores, hopefully your favourite one! A big thank you for pre-ordering & spreading the word to others who may be interested.

Honouring lack

Navigating Existential Judgment

Blog by Valerie

Lately some protracted conflicts have come to the surface in my life at a macro level in the world, and at a micro level in my daily life. I have been praying quite a lot since the war in Ukraine broke out, where my Jewish-Sumerian ancestors spent many generations living, and more recently about the war in the Middle East. It seems to me like there is existential war and rejection going on based in judgment, where one or more parties to a conflict feel they are fighting to exist in the minds and hearts of the other.

I find existential judgement incredibly dangerous and damaging and see it as the root of genocide. It feels to me like a hand rejecting its own finger. If we believe in a Creator with wisdom our human minds cannot comprehend, how can we put ourselves in the position of judging what the Creator brought into being? And to say another is allowed to exist elsewhere (NIMBY) is still judgmental, for if we force another to leave their home and live on different lands, we change their and our identities by disconnecting people from their earthly homes and playing the roles of victims and offenders.

On a micro level I’m seeing this thinking play out in some righteous social justice warrior crusades around me. I find the concept of ‘rights’ to be violent, though it has obvious practical value to create baseline standards for society. If we didn’t existentially judge certain struggles and behaviours as deeming people unworthy of housing or health care or food, then rights would simply represent social baselines we collectively agreed upon as minimum standards of care for all of us humans living here. But if a single mother can’t afford housing, or a man with mental illness isn’t at retirement age but can’t hold down a job, we don’t collectively agree how (or sometimes even if) to support their survival. Rights then get used in a forceful way to push a majority social group’s minimum standard of support onto the collective, and thus they often need to be en-forced. And when we are judged and caught up in the rights battles we feel, rightly so, like we are fighting for our survival. (See survival strategies blog)

I agree with Jungian scientist Fred Gustafson that the Western mind is “having a massive collective nervous breakdown” and is going to “war to determine whose anthropocentric [world]view is most valid [while] the earth and all its inhabitants [] suffer.”[1] I have not found sufficient solace for survival in the Western world alone.

For me it has been vital to live in two worlds: (1) a social reality that is based on a Western worldview, and (2) an earth-based reality based on an Indigenous worldview. When I’m caught up in a survival struggle in the Western world that’s terrifyingly real, and I’m feeling rejected and judged and shamed and angry, I can spiritually connect with the knowing from the Land and my ancestors that I’m not only allowed to exist but that I am wanted. This powerful medicine is all I have found that alleviates my existential wounds. Without it I feel like I would not still be here on this Earth, as my roots would have rotted and not been able to hold up the rest of my inner tree of life. (Image from here)

For me it has been vital to live in two worlds: (1) a social reality that is based on a Western worldview, and (2) an earth-based reality based on an Indigenous worldview. When I’m caught up in a survival struggle in the Western world that’s terrifyingly real, and I’m feeling rejected and judged and shamed and angry, I can spiritually connect with the knowing from the Land and my ancestors that I’m not only allowed to exist but that I am wanted. This powerful medicine is all I have found that alleviates my existential wounds. Without it I feel like I would not still be here on this Earth, as my roots would have rotted and not been able to hold up the rest of my inner tree of life. (Image from here)

If you’re also feeling some pain and heaviness about existential judgement and its impact, here are a few things that help me keep my spirits strong:

- Grieving is a way I like to express angry energy to avoid getting overwhelmed by righteousness and gain clarity which fights, if any, feel right for me to engage in, and what that means practically. You may prefer to yell and scream or throw things or punch a bag instead, so however you express anger to avoid it overwhelming you is helpful.

- Connecting with the land and ancestors where I am offers me powerful healing. I may give offerings as simple as feeding a bird or picking up rubbish, or as profound as a placenta burial or smoking/smudging ceremony. I may also cultivate a sit spot on the land, walk barefoot, and tend a tree altar. There are so many more ways to connect with the land where you live, these are but a few. The reverence we bring to the action we choose matters more, I think, than exactly what we do.

- Letting go of black-and-white, objective, judgmental thinking is something I am very fierce with myself about. Humility is an important value to me, so I ensure that even when I feel certain or highly confident about something that I carry a little bit of doubt. For example, I feel highly confident that child sex abuse (link) is a damaging act that is wrong to do. Yet my intense journey of seeking to heal that wound has brought me so much wisdom and peace. Spiritual gifts often thrive in grey, paradoxical spaces.

Altering my consciousness is another survival tool I use daily, primarily through embodied meditations and drum journeys. I do it to heal trauma, connect with ancestors and other spiritual guidance, and seek tools for every day survival such as deeper spaces of compassion or peace. However you are able to sink deeper than your everyday ‘known’ and familiar thought loops can bring you some healing. I do find, however, that embodied practices (such as using sound or dance or breath techniques) are more powerful than mind-based practices (such as meditating through your third eye or simply watching your thoughts).

Altering my consciousness is another survival tool I use daily, primarily through embodied meditations and drum journeys. I do it to heal trauma, connect with ancestors and other spiritual guidance, and seek tools for every day survival such as deeper spaces of compassion or peace. However you are able to sink deeper than your everyday ‘known’ and familiar thought loops can bring you some healing. I do find, however, that embodied practices (such as using sound or dance or breath techniques) are more powerful than mind-based practices (such as meditating through your third eye or simply watching your thoughts).

Thank you for reading this, and may your life be enriched (and even saved) by living in both worlds, as mine is.

[1] Gustafson, F. (1997). Dancing between two worlds: Jung and the Native American soul. Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press.

![]() If you value this content, please engage in reciprocity by living, sharing and giving.

If you value this content, please engage in reciprocity by living, sharing and giving.

Tattoos & Tradition

Blog by Valerie

This blog idea came to me a while ago when I read an article about the revival of Deq, a traditional tattooing technique in Kurdish and some other Arabic and Northern African cultures. I had always been told you can’t be buried in a Jewish cemetery with a tattoo, and something about this tradition resonated as more ancient and true to my Sumerian roots. The article explained that Deq is a form of worship, with tattooing the skin believed to also engrave a person’s soul. It is a women’s tradition that uses breast milk and another substance (such as soot) to create the ink. (Image from Wikipedia)

Deq differs greatly from modern conceptions of tattooing. While today individuals often get tattoos for decoration or to memorialise events, people, or beliefs, deq is traditionally done to request abundance, protection, blessings, or fertility from God.

Spiritual protection is a common reason for tattooing in Indigenous science. According to Western scientist Lars Krutak of the Smithsonian, traditional cultural tattooing is done for the following reasons:

- Adornment

- Identity

- Social status

- Therapeutic/Health

- Spiritual protection/Animal mimicry

(Krutak, L. (2015). The cultural heritage of tattooing: a brief history. In Tattooed skin and health (Vol. 48, pp. 1-5). Karger Publishers.) Most of these we can relate to today, though you may be wondering what therapeutic or health tattoos are. Among our ancient ancestors are tattooed ceramic figures that are over 6000 years old found in modern day Ukraine and Romania, and a 5000 year old mummy found preserved in ice in the Italian Alps who appears to have therapeutic tattoos in places on his body that look similar to a practice in traditional Asian cultural medicines. Such tattoos tend to be at joints and in the lower back. Tattooed mummies have also been found from Egypt to Siberia to Peru, and tattooed earthenwares of human or spirit figures have been found across the world from ancient Mississippi to Japan to the Philippines.

modern day Ukraine and Romania, and a 5000 year old mummy found preserved in ice in the Italian Alps who appears to have therapeutic tattoos in places on his body that look similar to a practice in traditional Asian cultural medicines. Such tattoos tend to be at joints and in the lower back. Tattooed mummies have also been found from Egypt to Siberia to Peru, and tattooed earthenwares of human or spirit figures have been found across the world from ancient Mississippi to Japan to the Philippines.

The word ‘tattoo’ was brought into English from James Cook’s 1770s journey to New Zealand and Tahiti, and supposedly inspired Western sailors to start a tradition of tattooing themselves to remember where they had traveled and people they missed at home. (Image of a Ta`avaha (headdress) with tattoos, Marquesas Islands, 1800s, via Te Papa from here) Though modern Polynesian tattoos differ by island and culture, generally tattoos are seen as a form of spiritual protection, cultural status symbols displaying rites of passage, and signifiers of ancestral lineage. Where tattoos are on the body, and what symbols and motifs are used, are also important as they link people to their Creation story:

The word ‘tattoo’ was brought into English from James Cook’s 1770s journey to New Zealand and Tahiti, and supposedly inspired Western sailors to start a tradition of tattooing themselves to remember where they had traveled and people they missed at home. (Image of a Ta`avaha (headdress) with tattoos, Marquesas Islands, 1800s, via Te Papa from here) Though modern Polynesian tattoos differ by island and culture, generally tattoos are seen as a form of spiritual protection, cultural status symbols displaying rites of passage, and signifiers of ancestral lineage. Where tattoos are on the body, and what symbols and motifs are used, are also important as they link people to their Creation story:

In Polynesian Mythology, the human body is linked to the two parents of humanity, Rangi (Heaven) and Papa (Earth). It was man’s quest to reunify these forces and one way was through tattooing. The body’s upper portion is often linked to Rangi, while the lower part is attached to Papa.

But tattoos have a long reputation as being lower class in Western culture due to their link with slavery and criminality, which can be traced back at least to ancient Greece and Rome, and likely to ancient Mesopotamia before then. As recently as in the 1800s in parts of Europe tattoos were being outlawed and seen as unChristian. And while the major world religions are not associated with traditional tattooing, there are exceptions, such as a Buddhist monastery in Thailand that “anchors” people into scripture with tattoos. (Image from here of Angelina Jolie). And while I can’t speak for how locals feel about Angelina’s tattoos (she was given Cambodian citizenship and adopted a child there, so she has come cultural connections), I feel uncomfortable about the amount of cultural appropriation that goes along with tattooing in

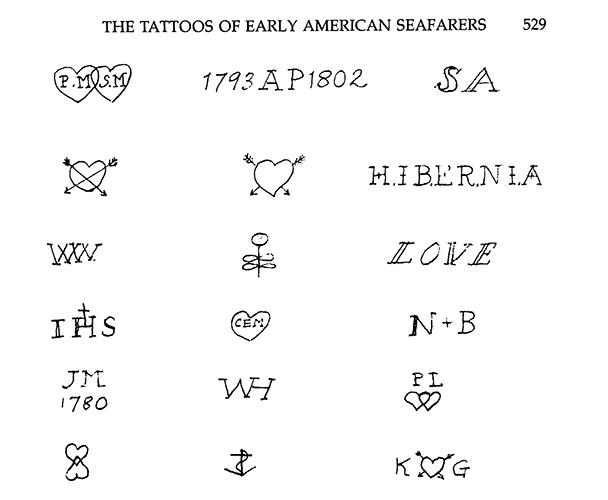

And while I can’t speak for how locals feel about Angelina’s tattoos (she was given Cambodian citizenship and adopted a child there, so she has come cultural connections), I feel uncomfortable about the amount of cultural appropriation that goes along with tattooing in  Western culture. I remember a trend some years ago of getting Chinese characters tattooed without many people even knowing or speaking the language. (I used to wonder how people weren’t scared they were lied to about what their tattoo said!) And many modern designs in Western culture have originated from those early sailors’ tattoos in the 1700s and 1800s. However, many have not, and where some celebrities like Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson express Samoan heritage through tattoos, others like Mike Tyson who is not of Maori descent has a ta moko design on his face (See this article on a history of tattooing in the U.S. by Sara Etherton). (Image from Visual log of tattoos seen on sailors in a survey done in 1809. (Ira Dye, “The Tattoos of Early American Seafarers, 1796-1818,” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 133, no. 4 [1989]: 520-554. accessed here).

Western culture. I remember a trend some years ago of getting Chinese characters tattooed without many people even knowing or speaking the language. (I used to wonder how people weren’t scared they were lied to about what their tattoo said!) And many modern designs in Western culture have originated from those early sailors’ tattoos in the 1700s and 1800s. However, many have not, and where some celebrities like Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson express Samoan heritage through tattoos, others like Mike Tyson who is not of Maori descent has a ta moko design on his face (See this article on a history of tattooing in the U.S. by Sara Etherton). (Image from Visual log of tattoos seen on sailors in a survey done in 1809. (Ira Dye, “The Tattoos of Early American Seafarers, 1796-1818,” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 133, no. 4 [1989]: 520-554. accessed here).

I have two tattoos. The first commemorates a flower I have a cultural connection with as well as a number, a colour, and some simples values; the second commemorates an insect I have a cultural and personal connection with. I got them both with close friends at the time during important moments in my life to mark endings/beginnings. Their placement is interesting – one on my right hip, and one on my left foot. I trust the intuition of those choices. I don’t notice them much anymore, they just feel like part of the fabric of me, and I’m thankful that though I got them when I was young, I still appreciate their presence on my body, and I have no need to be buried in a Jewish cemetery anyway.

Exercise: Reflect on any tattoos you have (or have considered getting). How do you feel about them – their aesthetic, meaning, and history? Is there anywhere you would or would not get a tattoo? Do you resonate with the idea that they connect you with your Creator or that they imprint onto your soul?

![]() If you value this content, please engage in reciprocity by living, sharing and giving.

If you value this content, please engage in reciprocity by living, sharing and giving.