![]() If you value this content, please engage in reciprocity by living, sharing and giving.

If you value this content, please engage in reciprocity by living, sharing and giving.

Tag Archives: decolonising

Vlog 1 – Winter Solstice

![]() If you value this content, please engage in reciprocity by living, sharing and giving.

If you value this content, please engage in reciprocity by living, sharing and giving.

Is it worth decolonizing my Filipino spirituality and mentality?

Blog by Ellis Bien Ilas

“The Filipinos of today are the happiest people I know. Why revisit the past and why does it matter now?” She told me with an unsure smile. I only just met her for the first time five minutes ago and somehow, our conversation took an unexpected dip into the stories rarely told territory.

When two strangers realise they’re both Pinoys because curiosity has prompted either of them to ask “Are you Filipino?”, there’s typically a surge of excitement when it’s a match. Usually, I reply by either talking about how long since I’ve been back in the Philippines or how much fun I had in my most recent trip. In this case, I had just returned from a trip to my homeland after a 5 year drought.

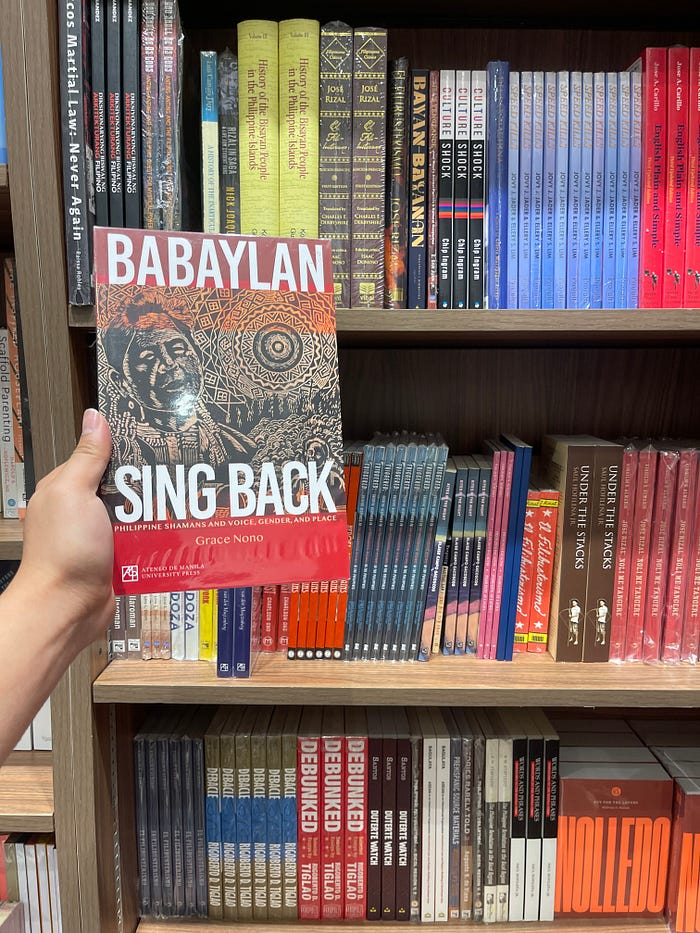

I casually recounted that while my trip was short and sweet, I was also on a mission to discover some local books on Filipino History. A quest that took me at least 9 book stores until a kind soul directed me to a shelf filled of said books on the second last day of my trip. It was a welcome relief after being repeatedly directed to the Filipino cookbooks section in my prior search.

Back to our unplanned discourse, I couldn’t possibly not share a tidbit or two about how aghast I was at what I’ve learned so far. Especially how our distant relatives have been wrecklessly jostled about from the Spanish to the Americans in deeply degrading (and staged) circumstances.

“…why does it matter now?” she recoiled back.

The sound of my name being called broke my reverie as I mulled her question. I was in an animal shelter and fortunately, it was my time in the queue to be attended to.

Being a Filipino-Australian who has been living in Australia since I was eight years old, I have also felt a gnawing inkling that now would be a great time in my life to rediscover my Filipino roots.

How does one start though? Scholarly articles and the very limited Filipino history ebooks on Amazon points to the fact that the colonial legacy of the Philippine’s past has left deep scars in the Filipino psyche, including “internalised oppression, self-hatred and colonial mentality” (David & Okazaki, 2006).

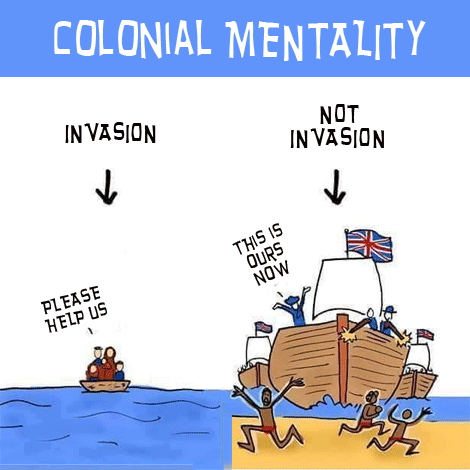

Hang on. Colonial Mentality? What does that actually mean?

Colonial Mentality

According to Nadal et al. (2016), colonial mentality refers to the internalisation of colonial values, beliefs and practices that devalue Filipino culture, language and identity. This can manifest as embarassment or feelings of inferiority over Filipino tradition and practices.

According to Nadal et al. (2016), colonial mentality refers to the internalisation of colonial values, beliefs and practices that devalue Filipino culture, language and identity. This can manifest as embarassment or feelings of inferiority over Filipino tradition and practices.

I recall when I first moved here in Sydney, Australia on several occassions, how several of my Filipino peers more often than not, proclaimed they were Fillipino-Spanish (even if that was 1/32th in bloodline). (Image from here)

“It just makes me sound more interesting you know. I’m not just another flip (Inner West Sydney slang for Filipino back in that time) who’s also a fob (fresh off the boat)”, I vividly recall an acquaintance disclosing.

David and Okazaki (2006, p.335) defines colonial mentality as “the conscious or unconscious acceptance of the belief that traits, values and practices associated with the coloniser are inherently superior to those associated with the colonised”.

To dive a little deeper, the authors developed the Colonial Mentality Scale to measure colonial mentality, which includes the following dimensions:

1. Belief in the superiority of Western physical features (e.g., light skin, straight hair)

2. Belief in the superiority of Western cultural values (e.g., individualism, direct communication)

3. Belief in the superiority of Western education and credentials

4. Belief in the superiority of Western technology and innovation

5. Belief in the superiority of Western religion and morality

The authors found that colonial mentality was significantly associated with lower self-esteem, higher acculturative stress, and lower levels of Filipino cultural values and practices among Filipino Americans.

So basically, colonial mentality has negative consequences for our mental health and well-being.

Decolonizing the Filipino Spirituality

Mention the word spirit or espiritu to a Filipino and you’ll either be discussing about perceived ghost sightings/apparitions (which stems from one of the Philippines’ pre-colonial belief systems referred to as animism — the belief that objects, places or creatures all possess a distinct spiritual essence) or, you’d be discussing the divine power of the Holy Spirit (through the lens of the Romantic Catholic faith).

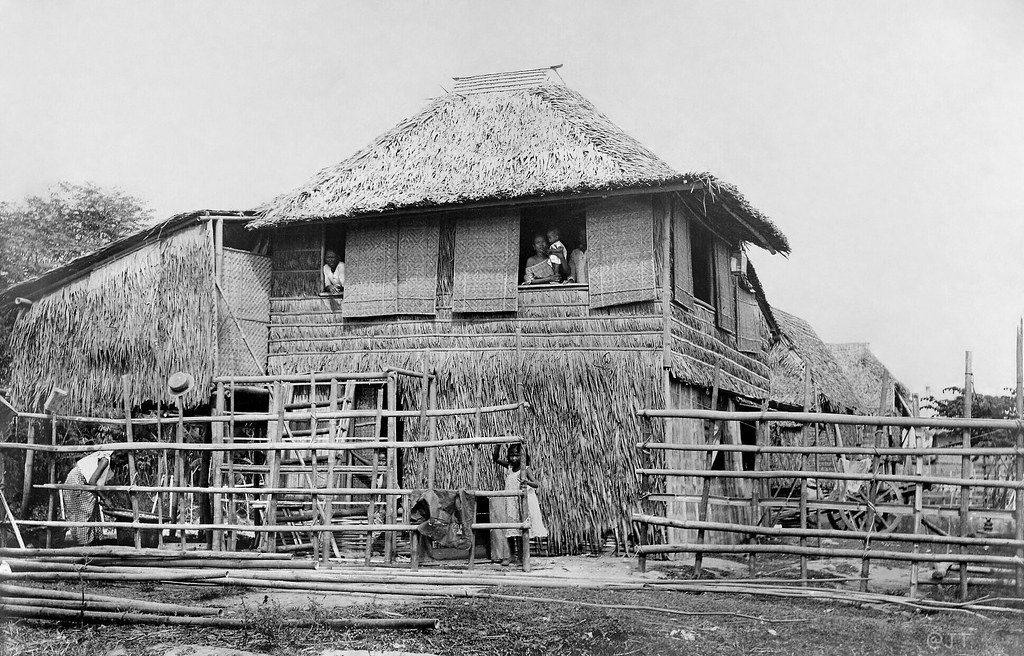

Constantino (1975) argued that Spanish colonialism and Catholicism had a profound impact on the Philippines, including the suppression of indigenous spirituality and cultural practices (which were largely based on animism), leading to the creation of a colonial and clerical elite. It also strongly impacted Filipino values and beliefs, how Filipino society is organised and the perpetuation of patriarchal and authoritarian structures of power, gender inequality and resistance to social and political change. (Image of pre-colonial Philippines house from here)

Constantino (1975) argued that Spanish colonialism and Catholicism had a profound impact on the Philippines, including the suppression of indigenous spirituality and cultural practices (which were largely based on animism), leading to the creation of a colonial and clerical elite. It also strongly impacted Filipino values and beliefs, how Filipino society is organised and the perpetuation of patriarchal and authoritarian structures of power, gender inequality and resistance to social and political change. (Image of pre-colonial Philippines house from here)

Let’s look at the typical Filipino family unit. Respecting and obeying Filipino parents and elders are deeply ingrained value and practice that is often associated with the way Catholicism has spread in the Philippines. These values and practices are based on the belief that Filipino parents and elders have the ultimate authority and control over their children and younger family members, and that their decisions and actions should not be questioned or challenged.

However, this value and practice can also perpetuate toxic and abusive dynamics in the Filipino family unit, particularly in relation to the reinforcement of authoritarian structures of power. For example, Filipino parents and elders may use their authority and control to enforce strict and oppressive rules and expectations, such as the control of their children’s education, career, and relationships; the restriction of their freedom and autonomy and the perpetuation of gender stereotypes and roles.

These dynamics can lead to unknowingly abusing that power, such as the emotional, physical, and sexual abuse of children and younger family members; the neglect and marginalization of their needs and rights, and the undermining of their agency and participation.

In light of the above, I’m not saying that Catholicism was all doom and gloom. I acknowledge that it also helped develop the Philippines through education and healthcare, as well as a sense of community and solidarity (which appears to still hold strongly today). However, it has caused issues still pervasive today. Problems that manifest in everyday life and I would imagine, most Filipino family units. Problems that I’ve seen myself and maybe, you have too. It’s possible that you have also considered, in the grand scheme of things, how did we get here and what can I do about it?

So… is it worth decolonizing my Filipino spirituality and mentality?

Considering the complex, multifaceted and evolving nature of the process of decolonisation, I don’t think I can reach a point and say, yeah, I’ve become decolonized now. Far from it.

But I am interested in improving my mental health and well-being, and this aspect of decolinization is a part of that process.

Despite this being in the making in the past few years, I’ve really only just taken my first few steps. My goal is to share this ever-evolving journey with others who may have had this spark lit within them. I’m curious to hear from you.

References

Constantino, R., & Constantino, L. R. (1975). The Philippines: A past revisited (Vol. 1). Quezon City: Renato Constantino.

David, E. J. R., & Okazaki, S. (2006). Colonial mentality: a review and recommendation for Filipino American psychology. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 12(1), 1.

Nadal, K. L. (2020). Filipino American psychology: A handbook of theory, research, and clinical practice. John Wiley & Sons.

![]() If you value this content, please engage in reciprocity by living, sharing and giving.

If you value this content, please engage in reciprocity by living, sharing and giving.

Warriorship

Blog by Lukas

Are the most prescient ideas and images that come to mind when you think of the word “warrior” all about physical strength, toughness, and violent conflict? I doubt you’re alone. To borrow a trick from Valerie, if you online image search the word “warrior” the first things that come up are virtually all men and related to physical violence, specifically some new television show that evidently involves a lot of arse kicking. The story is similar if you try “female warrior”.

The technical definition of a warrior in the English language supports this narrow view, being rooted in a French word guerroieor meaning “one who wages war”. Most definitions of warrior relate to waging armed conflict, specifically those who have some kind of specialised role in doing so. (Image from here)

The etymology of the word “war”, however, is much more interesting, seemingly originating with broader concepts that include difficulty, dispute, and hostility. According to etymonline.com, if you follow the known Proto-Germanic cognates as far back as they go, you arrive at a word that means “to bring into confusion”.

This is fascinating to me on a number of levels. Not least of all because virtually all first-person accounts of war I have read describe some manner of confusion and chaos to a degree that was unexpected to the writer. My flailing fist fights over the years confirm this; and as “Iron” Mike Tyson said:

So if war is to some degree about confusion and chaos, perhaps the true warrior is someone who uses their power to bring these things back into a calmer balance? This then is about a warrior responding to and resolving conflict rather than instigating it, even if it is they who strike first. Without doubt there is a rightful place for violence in this, but also many other elements. Sticking to the realm of the physical, another version of the warrior could be a woman in labour finding her strength and power and calmly birthing just when things were at their most chaotic and the pain most intense. (Image from here)

But if we are to use this warrior concept to its fullest extent, literally and metaphorically, perhaps the most important thing is to apply it across the medicine wheel. So this gives us emotional, spiritual, and mental warriors; any and all ways in which a being can use their strength and power to bring conflict and disorder back into balance.

Note that this bigger version of warriorship does NOT just mean these other aspects of warriorship being in service of physical violence, such as mental energy being devoted to better weapons technology, or emotional quieting and centring that improves fighting ability. It means recognising their deep value to our being in and of themselves and together in balance.

This topic came to me when thinking about men and masculinity in the context of healing and reconciliation between Anglo-Celtic Australians and Aboriginal Australians. If we restrict our thinking about and valuing of warriorship to literal, physical combat, this makes such healing hard, such was the intense lopsidedness of the physical contest.

I don’t think it is controversial to say that in the world of Aboriginal Australians, weapons and warfare were just one part of what made men and warriors in those cultures whole and powerful. The weapons they had been using for millennia more than did the job they were needed for. Europeans, on the other hand, were by 1788 riding a wave of centuries of escalating prowess in using violence, supercharged by technology and in service of greed. Warriorship caused more conflict and trauma than it resolved.

With this fuller version of warriorship comes some understanding of what I as an Anglo-Celtic colonist lack, and what I need for healing. I don’t yet value my heart and spiritual warriorship enough.

On both the oppressor/colonist side, and the survivor/colonised side of this ledger is ample reason to grow through helping each other to see warriorship more fully. When we do this we’ll need no self-shaming to see the deep value of the balanced warriorship of Aboriginal masculine culture. We colonists can learn what being a whole mature warrior means, and Aboriginal men can learn to value who they are more fully. Then we can do ceremony to bring the conflict and disorder back into balance. (Image from here)

Exercise: Taking a strengths-based stance, think about how your sacred masculine (regardless of your gender) displays warriorship across the Medicine Wheel.

Exercise for Australians: If you are doing an Acknowledgement of Country (especially when there are only men present), try acknowledging the Aboriginal warriors as well as Elders.

![]() If you value this content, please engage in reciprocity by living, sharing and giving.

If you value this content, please engage in reciprocity by living, sharing and giving.