Blog by Valerie

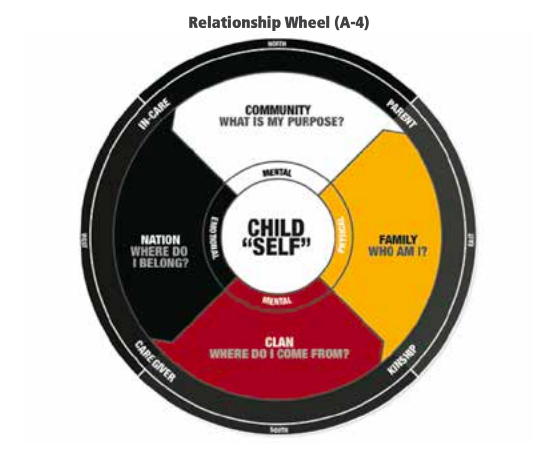

Some studies of newborns suggest that humans’ most fundamental need is to be part of a culture, to engage with their social environment and try to make sense of their surroundings. It can be helpful to conceptualise culture as a “cognitive orientation” instead of dividing people into racial or ethnic groups (Brubaker et. al, 2004), because “the most significant features of any child’s environment are the humans with whom they establish close relationships” who these days are often multi-cultural (Woodhead, 2005). Raising children is a process by which “we try to achieve cultural goals and well-being for ourselves and our children,” through pathways “determined by cultural activities organised into routines of everyday life” (Weisner, 1998). Children learn cultural models of living through relationships with parents, close kin and social institutions, during which time their young minds develop interdependently within their cultural context. This graphic shows elements of Yolgnu (Australia) child-rearing:

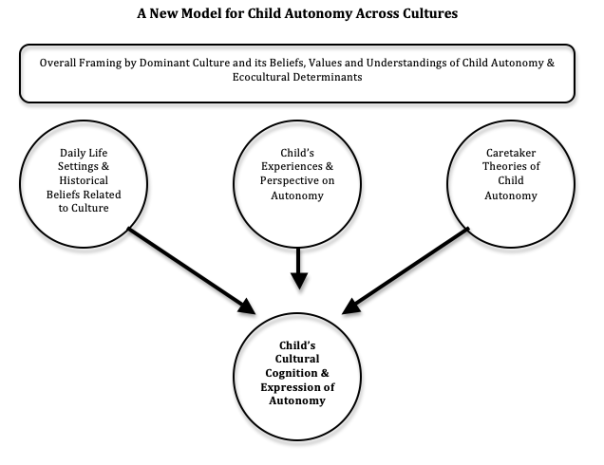

The developmental niche theory provides a framework for connecting culture with childrearing (Super & Harkness, 1994). A child’s physical and social settings, cultural customs of childcare, and psychology of caretakers form a “developmental niche”, and the eco-cultural niche theory identifies five areas of child development: (1) health and mortality; (2) food and shelter; (3) the people likely to be around children and what they are doing; (4) the role of women and mothers as primary caretakers; and (5) available alternatives to cultural norms (Harkness & Super, 1983). Some years ago I worked with social worker Amy Thompson to develop the following model:

In modern Western culture, there’s a lot that is broken, out of balance, and unwell. To intervene in any of the bubbles above will alter a child’s (or inner child’s) cultural identity and autonomy. And there’s a lot of wisdom in Indigenous childrearing.

Unlike the paternalistic culture many of us are familiar with, Earth Ethos parenting respects children’s agency. Autonomy is the freedom “to follow one’s own will” (Oxford English Dictionary). It’s important to note that autonomy is not the same as agency, or a child’s capacity for intentional, self-initiated behaviour. In “central Africa children are trained to be autonomous from infancy. They are taught to throw spears and fend for themselves. By age three they are expected to be able to feed themselves and subsist alone in a forest if need be” (quoted in Rogoff, 2003). Aka Pygmy children in Africa have access to the same resources as adults, whereas in the U.S. there are many adults-only resources that are off-limits to kids, and Among the Martu people of Western Australia, the worst offence is to impose on a child’s will, even if that child is only three years old” (Diamond, 2012). Yet Western children tend lack much autonomy and agency until they turn 18. One scholar suggests that four main ideas have shaped Western civilisation’s parenting practices:

- The young child is naturally wild and unregulated, and development is about socialising children to their place within society (e.g. Thomas Hobbes, 1588-1699);

- The young child is naturally innocent, development is fostered by protecting the innocence and providing freedom to play, learn and mature (e.g. Jacques Rousseau, 1712-1778);

- The young child is a ‘tabula rasa’ or blank slate, development is a critical time for laying the foundations that will enable children to reach their potential (e.g. John Locke, 1632-1704);

- The young child is shaped by nurture and nature, development is an interaction between potential and experience (e.g. Emmanuel Kant, 1724-1804) (Woodhead, 2005).

European American (mostly middle class) mothers have been extensively studied, and their parenting practices dominate popular culture and academic literature, yet a study across twelve countries found their beliefs and behaviours abnormal in an international context (Woodhead, 2005). Common conflicts between Western and other cultures were:

- Emphasis on the individual versus emphasis on the family;

- Autonomy versus interdependence;

- Youth culture versus respect for elders;

- Unisex versus gender differences;

- Individualism versus communal; and

- Competition versus cooperation (Friedman).

In most Indigenous cultures child development is not led by parents but is seen to naturally emerge through a network of kinship care. Children are seen as autonomous and encouraged to learn through experience rather than explicit instruction and rules (Sarche et. al, 2009). Parents avoid coercion and corporeal punishment, instead using storytelling and role modelling to discipline. This teaches natural consequences and allows parents to avoid imposing punishment. For example, this article shares a story of a preventive parenting practice by which an Inuit mother who asks her two-year-old son to throw rocks at her on the beach. He hits her leg, and she says, “Ow! That hurts!” to show him the consequence of hitting someone. And even if he kept throwing rocks after she showed the pain it caused, traditional Inuit still do not yell at children: “yelling at a small child [is seen] as demeaning. It’s as if the adult is having a tantrum; it’s basically stooping to the level of the child.” Child attachment differs from Western culture as well:

It isn’t just about attachment to the mother or the biological parents, but attachment to all of my relations. Practices and ceremonies were meant to build attachments to all parts of the community and the natural world, including the spirit world.–Kim Anderson, Métis (Canada)

An Anishinabe (Canada) woman explains the development of her attachment to Country through bush socialisation:

The absence of fences, neighbors and physical boundaries led way for the natural curiosities of a child to grow and be nurtured…I learnt to search for food, wood, plants, medicines and animals. Trees provided markers; streams, rivers and lakes marked boundaries, plants indicated location, and all this knowledge I developed out of just being in the bush…My bush socialization has taught me to be conscious of my surroundings, to be observant, to listen and discern my actions from what I see and hear. Elements of the earth, air, water and sun have taught me to be aware and move through the bush accordingly. (Image from here)

Ceremony is modelled from a young age. In this video, a Yolgnu (Australia) boy is barely walking and already learning traditional dances to connect with his community and his ancestors, and by the end of the video at age 7 is participating in a funeral dance:

This medicine wheel from a childrearing manual for First Nations Canadians further demonstrates that in an Earth Ethos, children are seen as autonomous and interconnected, and shown how to live in balance with all my relations.

Exercise: What parenting perspective or childrearing practice would you like to improve in your life? Using suggestions from this post, researching on your own, or your own insight and intuition, what step could you take today to move further towards balance?

![]() If you value this content, please engage in reciprocity by living, sharing and giving.

If you value this content, please engage in reciprocity by living, sharing and giving.

I’d be interested to know about the different approaches taken across similar contexts in order to understand the way parenting approaches are affected by and affect the environment (used very broadly).

If there’s one thing that Jared Diamond has really sold me on is the notion that culture, or behavioural norms, don’t exist in the bubble. You have clear ways in which environment affects the way people behave, and then variation within that. So be interesting to look at urban settings in Asia vis-a-vis the same in Europe/America, and similarly the variations across indigenous cultures.

I guess the hypothesis is that changing our parenting styles in a bubble is difficult. We need to collectively address the environment we co-create indirectly. For example, if there is a huge social penalty to be paid for certain behaviour, it’s not actually serving that child to not set hard boundaries, or at least teach them somehow that hard boundaries are out there.

I mean, I guess you could say “in this house/community we see it this way, but out there they look at things this way” and e.g. use an Inuit parenting technique like a story rather than something punitive to make sure the child learns what they need to know…but I must also profess to wanting to raise boatmen too…with some lived experience of what the biggest mob is going through.

LikeLike