![]() If you value this content, please engage in reciprocity by living, sharing and giving.

If you value this content, please engage in reciprocity by living, sharing and giving.

Tag Archives: ceremony

Birth as Ceremony

Blog by Valerie, following recent presentations with breastfeeding and pregnancy groups

We do ceremonies at important moments in our lives, such as weddings, graduations, and funerals. Ceremonies support us to gain knowledge, purify our spirits, and honour life. They can be as simple as a small act done with sacred intention, or as elaborate as a religious confirmation.

“In traditional practices and rituals, birthing involved more than the physical health of the mother and baby. Giving birth was a process of initiation and belonging to the culture that created spiritual links to the land and the ancestral Dreaming.”—Best, O., & Fredericks, B. (Eds.). (2021). Yatdjuligin: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander nursing and midwifery care. Cambridge University Press.

The birthing journey, from pregnancy to postpartum it is seen in Indigenous science as a time of spiritual initiation for the new mother. Initiations are transitional ceremonies that lead us through Earth’s cycle from life to death and rebirth into a new identity. For first time mothers, this journey is a profound shift from being a maiden into be-coming a mother, and for all mothers it is a journey of be-coming a mother within a new relationship.

Initiation ceremonies have three phases:

- Separation from daily reality;

- Ordeal or trauma; and

- Return or rebirth.

In an Indigenous worldview, the mother is seen as a conduit between the spiritual and physical worlds, and birthing trauma as a meaningful initiation into spiritual adulthood. In fact, many Indigenous cultures have initiation rites only for young men, because childbirth (as a birthing mother, through miscarriage, and/or through supporting birthing women) is considered to be the initiation process naturally built into women’s bodies. (Image: Natural Birth Art Print by Sean Frosali, Society6)

In an Indigenous worldview, the mother is seen as a conduit between the spiritual and physical worlds, and birthing trauma as a meaningful initiation into spiritual adulthood. In fact, many Indigenous cultures have initiation rites only for young men, because childbirth (as a birthing mother, through miscarriage, and/or through supporting birthing women) is considered to be the initiation process naturally built into women’s bodies. (Image: Natural Birth Art Print by Sean Frosali, Society6)

Phase 1: Separation from daily reality – being pregnant

The moment a woman is pregnant, she and everyone she meets is in ceremony…The womb is our first orientation on Earth.–Patricia Gonzalez, Red Medicine: Traditional Indigenous rites of birthing and healing

During pregnancy, traditional ceremonies are based on:

-

- Mothers and elders sharing wisdom about birthing, breastfeeding and childrearing;

- Cleansing the mother’s space, including her body and home (i.e. massage, smudging);

- Community support with certain tasks around the house for the mother;

- Taboos and norms about foods, drinks, and activities a mother ought to do or avoid;

- Honouring the babies’ soul entering the womb and protecting the mother and baby (i.e. with amulets, prayers, and rituals, and avoiding aspects of life such as funerals);

- Helping to welcome and support a new baby (i.e. to ease a first time mother’s anxiety, baby showers).

There are of course many cultural variations on such ceremonies. One example is in parts of India where there is a sort of baby shower called a Valaikaapu in which the mother-to-be is sung to by other women, adorned with bangles, soothed from anxiety with herbal treatment on her hands and feet, and fed traditional nourishing foods. After this ceremony in the third trimester, the mother-to-be traditionally stays at her parents’ house until the baby is born. Another example occurs in parts of Indonesia also begins in the third trimester with the mothers’ parents bringing food to their son-in-law’s family, and the mother ceremonially feeding her pregnant daughter before everyone else eats. The parents-to-be are then given blessings and encouragement by both the whole family, including being wrapped in traditional fabric as a symbol of strength for their union through the birthing journey (Silaban, I., & Sibarani, R. (2021). The tradition of Mambosuri Toba Batak traditional ceremony for a pregnant woman with seven months gestational age for women’s physical and mental health. Gaceta Sanitaria, 35, S558-S560.). (Image from here)

There are of course many cultural variations on such ceremonies. One example is in parts of India where there is a sort of baby shower called a Valaikaapu in which the mother-to-be is sung to by other women, adorned with bangles, soothed from anxiety with herbal treatment on her hands and feet, and fed traditional nourishing foods. After this ceremony in the third trimester, the mother-to-be traditionally stays at her parents’ house until the baby is born. Another example occurs in parts of Indonesia also begins in the third trimester with the mothers’ parents bringing food to their son-in-law’s family, and the mother ceremonially feeding her pregnant daughter before everyone else eats. The parents-to-be are then given blessings and encouragement by both the whole family, including being wrapped in traditional fabric as a symbol of strength for their union through the birthing journey (Silaban, I., & Sibarani, R. (2021). The tradition of Mambosuri Toba Batak traditional ceremony for a pregnant woman with seven months gestational age for women’s physical and mental health. Gaceta Sanitaria, 35, S558-S560.). (Image from here)

Phase 2: Trauma/ordeal – birthing

In the Mohawk language, one word for midwife…describes that “she’s pulling the baby out of the Earth,” out of the water, or a dark wet place. It is full of ecological context. We know from our traditional teachings that the waters of the earth and the waters of our bodies are the same.

—Rachel Olson, Indigenous Birth as Ceremony and a Human Right

During and immediately following birth, traditional ceremonies are based on:

-

- Birthing sites in sacred spaces indoors (e.g. sweat lodges) and outdoors (e.g. natural pools);

- Taboos about labour being quiet or loud, and women’s positions (e.g. squatting);

- Norms about partners being present at birth, or having their own tasks to do for the baby;

- Use of traditional herbal steams and poultices to cleanse the womb, stop bleeding, and help milk start flowing following the birth;

- Protecting the baby and mother;

- Umbilical cord ceremonial clamping and/or saving, or lotus birthing;

- Sensual imprinting for the newborn through wrapping them in traditional clothing, jewellery, fur, and/or blankets; and

- Body wrapping and womb re-warming practices for the mother after birth.

There are also many cultural variations for these ceremonies. For example, in Japan umbilical cords are saved and presented to new mothers in keepsake wooden boxes at hospitals. This tradition is meant to keep a good relationship between the mother and baby, and sometimes the box is given to the adult child when they leave home or marry to symbolise a separation in an adult-to-adult relationship. In Australian Aboriginal cultures, cultural birthing areas utilised natural depressions and sacred spaces such as rock formations, caves and water holes, to spiritually connect the child to their Country and their ancestors. Women followed ‘Grandmother’s Law’ which often included practices such as squatting over the steam of traditional medicinal plants after birth to prevent infection, how to name the child, and when the child would meet their father (Adams, K., Faulkhead, S., Standfield, R., & Atkinson, P. (2018). Challenging the colonisation of birth: Koori women’s birthing knowledge and practice. Women and Birth, 31(2), 81-88). (Image from here)

There are also many cultural variations for these ceremonies. For example, in Japan umbilical cords are saved and presented to new mothers in keepsake wooden boxes at hospitals. This tradition is meant to keep a good relationship between the mother and baby, and sometimes the box is given to the adult child when they leave home or marry to symbolise a separation in an adult-to-adult relationship. In Australian Aboriginal cultures, cultural birthing areas utilised natural depressions and sacred spaces such as rock formations, caves and water holes, to spiritually connect the child to their Country and their ancestors. Women followed ‘Grandmother’s Law’ which often included practices such as squatting over the steam of traditional medicinal plants after birth to prevent infection, how to name the child, and when the child would meet their father (Adams, K., Faulkhead, S., Standfield, R., & Atkinson, P. (2018). Challenging the colonisation of birth: Koori women’s birthing knowledge and practice. Women and Birth, 31(2), 81-88). (Image from here)

Phase 3: Return/rebirth – becoming a mother

We believe in waiting until 30 days after the birth for any celebrations. In our tradition, we believe that the unborn child has a guardian angel, who is the previous mother of the child. If we celebrate the pregnancy publicly, the spirit of the previous parent might come and reclaim her child — so that the new mother loses her baby!—Vietnamese grandmother quoted in Cusk, R. (2014). A Life’s Work. Faber & Faber.

In the postnatal months, traditional ceremonies are based on:

-

- Protecting the baby and mother;

- Naming and welcoming the baby to the land and family;

- Building the newborn’s resilience with elements and weather;

- “Firsts” (i.e. baths, foods, laughs, rolling over, walking, etc.);

- Mother’s rest and recovery from birth (often 40 days); and

- Placenta ceremonies.

A sweet example of such a ceremony comes from the Navajo/Diné people of North America have a ceremony to honour the babies’ first laugh, and the person who gets the baby to laugh throws a party where guests are given salt on the baby’s behalf as a symbol of generosity since it was traditionally valuable and hard to get (Brown, Shane. (2021). Why Navajos Celebrate the First Laugh of a Baby. https://navajotraditionalteachings.com/blogs/news/why-navajos-celebrate-the-first-laugh-of-a-baby). Across the world in Egypt, on the child’s seventh day after birth, a Sebou’ ceremony welcomes the baby with a number of traditions related to the cultural meaning of the number seven, such as placing the baby in a sieve and shaking them to symbolise life becoming more dynamic outside the womb, then stepping over them seven times saying prayers for protection and obedience to their parents; a candlelit procession of smudging the house; and a drink to increase breast milk production (Gamal, A. (2015). The Sebou‘: An Egyptian Baby Shower, https://www.madamasr.com/en/2015/11/02/panorama/u/the-sebou-an-egyptian-baby-shower/). And in Nordic countries, babies are traditionally left to nap outside no matter the weather to build their resilience to the earthly elements. Called friluftsliv it translates to ‘open-air life’ and represents cultural importance of enjoying nature and the outdoors all year round (McGurk, L. (2023). Creating a stronger family culture through ‘friluftsliv’, Children’s Nature Network, https://www.childrenandnature.org/resources/creating-a-stronger-family-culture-through-friluftsliv/). (Image by Joey Nash)

A sweet example of such a ceremony comes from the Navajo/Diné people of North America have a ceremony to honour the babies’ first laugh, and the person who gets the baby to laugh throws a party where guests are given salt on the baby’s behalf as a symbol of generosity since it was traditionally valuable and hard to get (Brown, Shane. (2021). Why Navajos Celebrate the First Laugh of a Baby. https://navajotraditionalteachings.com/blogs/news/why-navajos-celebrate-the-first-laugh-of-a-baby). Across the world in Egypt, on the child’s seventh day after birth, a Sebou’ ceremony welcomes the baby with a number of traditions related to the cultural meaning of the number seven, such as placing the baby in a sieve and shaking them to symbolise life becoming more dynamic outside the womb, then stepping over them seven times saying prayers for protection and obedience to their parents; a candlelit procession of smudging the house; and a drink to increase breast milk production (Gamal, A. (2015). The Sebou‘: An Egyptian Baby Shower, https://www.madamasr.com/en/2015/11/02/panorama/u/the-sebou-an-egyptian-baby-shower/). And in Nordic countries, babies are traditionally left to nap outside no matter the weather to build their resilience to the earthly elements. Called friluftsliv it translates to ‘open-air life’ and represents cultural importance of enjoying nature and the outdoors all year round (McGurk, L. (2023). Creating a stronger family culture through ‘friluftsliv’, Children’s Nature Network, https://www.childrenandnature.org/resources/creating-a-stronger-family-culture-through-friluftsliv/). (Image by Joey Nash)

Placental ceremonies are based on traditional understandings of the placenta as a spiritual twin, a baby’s guardian angel, a ‘death’ gift offered to the Earth to give thanks for a healthy baby, and a carrier of a holographic imprint for the baby’s life on Earth. Most cultures bury the placenta (a few even give it funeral rites), some burn or eat it, and a few do lotus births (where the placenta stays attached to the baby until it dries out and falls off). The Hmong people in Laos believe a person’s spirit will wander the Earth and not be able to join their ancestors in the spirit world without returning to the place their placenta was buried and collecting it, and the word for placenta in their language translates as ‘jacket’ (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hmong_women_and_childbirth_practices). In Maori language in New Zealand, ‘whenua’ is the word for both ‘land’ and ‘placenta’, and after childbirth the placenta is buried on ancestral lands to strengthen a child’s connection to culture, often beneath a tree (Soteria. (2020). Māoritanga: Pregnancy, Labour and Birth. https://soteria.co.nz/birth-preparation/maori-birthing-tikanga/). Placentas are dried and eaten to support the mothers’ or baby’s strength in many places, from China to Jamaica to Argentina (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Human_placentophagy).

Placental ceremonies are based on traditional understandings of the placenta as a spiritual twin, a baby’s guardian angel, a ‘death’ gift offered to the Earth to give thanks for a healthy baby, and a carrier of a holographic imprint for the baby’s life on Earth. Most cultures bury the placenta (a few even give it funeral rites), some burn or eat it, and a few do lotus births (where the placenta stays attached to the baby until it dries out and falls off). The Hmong people in Laos believe a person’s spirit will wander the Earth and not be able to join their ancestors in the spirit world without returning to the place their placenta was buried and collecting it, and the word for placenta in their language translates as ‘jacket’ (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hmong_women_and_childbirth_practices). In Maori language in New Zealand, ‘whenua’ is the word for both ‘land’ and ‘placenta’, and after childbirth the placenta is buried on ancestral lands to strengthen a child’s connection to culture, often beneath a tree (Soteria. (2020). Māoritanga: Pregnancy, Labour and Birth. https://soteria.co.nz/birth-preparation/maori-birthing-tikanga/). Placentas are dried and eaten to support the mothers’ or baby’s strength in many places, from China to Jamaica to Argentina (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Human_placentophagy).

Today, it might be hard to decide what to do if you don’t know your Indigenous roots and their cultural traditions, and when because many of us birth in hospitals. I suggest relying on your intuition, and what resonates with you. Some ceremonies common across cultures that you may wish to do for yourself and your baby may relate to:

-

- Prenatal blessings to keep the mother and baby safe;

- Connecting the baby to the land and elements (earth, air, fire, water);

- Postnatal rituals to keep the mother and baby safe;

- Placenta burial; and/or a

- Naming ritual.

Keep in mind that you can’t do a ceremony wrong if your heart and intention are in it. The way you feel during and after the ceremony will show you how it went. For my child, we did a prenatal baby shower/blessing with friends and family in person and on Zoom, and we printed out the blessings for our home-birthing space, then ultimately buried them with the placenta a few months after the birth. We chose our baby’s first sensual experiences – sight, smell, touch, and hearing, as her first taste was breastmilk! We brought earth inside to touch to her feet to connect her to the land as she was born in winter, and her placenta burial ceremony was on land where her great-great-great grandmother was buried.

I hope this has given you some things to reflect on and ideas for celebrating your journey into be-coming a mother in a way that feels sacred and special to you and your family. (Two other blogs you may find interesting about my birth and early mothering experiences are: about spirit babies, and mothering amidst intergenerational trauma).

![]() If you value this content, please engage in reciprocity by living, sharing and giving.

If you value this content, please engage in reciprocity by living, sharing and giving.

What is Indigenous spirituality?

Blog by Valerie

A friend brought this question to me, and I thought it a good one to take on. For some, being ‘spiritual’ is like the U.S. Supreme Court decision about porn – ‘I know it when I see it’. For some it’s intertwined with religious rites. For me, spirit is an animating energy exhibited through an act or a relational dynamic that connects all of us beings on Earth. For example, the spirit of my relationship with my daughter is characterised by a lot of joy, and the spirit of my relationship with my dog is primarily one of companionship. Spirituality is cultural, and mine is Indigenous, based on an animistic understanding of the world. I see all beings on Earth, including rocks and even manmade plastic toys, as having spirit, some kind of animating energy.

(Typical image of ‘spirituality’ from here)

(Typical image of ‘spirituality’ from here)

Spirit with a capital S to me refers to a big creative and destructive energy that is more than any identity I can hold, of which I am a small part. Some say Great Spirit, some say God. Spirits plural to me refers to beings that I see in dreams or visions, or experience through the four invisible clair-senses (clairvoyance – seeing, clairsentience – feeling, clairaudience – hearing, claircognisance – knowing – described by Diné Elder Wally Brown as the counterparts to our five physical senses represented by our five fingers and the four spaces between them.)

So if this is what spiritual, Spirit, and spirits mean to me, what does it mean to ‘be spiritual’? First, it means acknowledging some energies/forces/beings that are too vast to be encompassed by an individual, or even our collective, human identity. Second, it means openness and awareness of the invisible clair-senses, and to experiences that are not explainable, or sometimes even experienceable, in materialist, physical terms.

My view is that children naturally see the world in an animistic way, and that through teachings begin to close their mind (and obscure their clair-senses) to other inputs. Recently a four year old asked me to read her a story about werewolves, then asked me if they were real. I said, I don’t know, what do you think? Have you seen one before? But her mother quickly jumped in to say that no, they’re not real. Of course she is entitled to teach her daughter that and presumably she believes that to be true. I have not personally encountered a werewolf in my dreams or visions (or the material world) but I tend to think that if such beings loom large in our collective human psyche, and even across cultures, that there is likely something to it.

How do we know the difference between a spiritual experience and our imagination? I have seen a lot of people struggle with this – with their minds tricking them into thinking they have encountered a Spirit, for example. For me the difference is in embodiment. And when in doubt, see if and how changes occur in your everyday life as a result of the insight or guidance you got. (Image from here)

How do we know the difference between a spiritual experience and our imagination? I have seen a lot of people struggle with this – with their minds tricking them into thinking they have encountered a Spirit, for example. For me the difference is in embodiment. And when in doubt, see if and how changes occur in your everyday life as a result of the insight or guidance you got. (Image from here)

That spiritual experiences are grounded in the land and embodied in everyday life is a foundation of Indigenous spirituality. In an Indigenous worldview, an identity is commonly seen as a collection of relational dynamics, including relationships with humans and non-humans. This interdependence is often honoured through totemic relationships and responsibilities to do rituals and ceremonies. If I see my identity and my very existence as tied to the water in a river nearby and the fish in it, then it makes sense to fight for their survival and even put my own life on the line. See this recent example from California regarding the centrality of salmon to Yurok, Karuk, and Hoopa Valley tribes.

This may seem extreme to Westerners, even environmentalists willing to put their lives on the line for Mother Earth, because it’s not just about how humans need water or fish to survive, it’s the particular patch of earth (or sea or sky) and relational responsibilities there that matter to your very existence. If those fish die, you die; there is no supermarket to run to for other food. If you have to leave your land, you may get killed by others when you go onto their lands, or you may die not knowing how to survive there and live in a sustainable healthy way there.

(Art by Cheryl Davison, Yuin woman, of the pregnant mother spirit of Gulaga mountain, protector of the land we are now grateful to call home, from this site)

(A photo of me in front of Gulaga taken a few years ago by Lukas before we knew we would be moving onto her country)

Western counsellors talk a lot about attachment theory. Right now when my baby cries (or is about to cry) I feel such pain inside, and such an urge to help her, I have to respond. Imagine feeling pain like that when a sacred site you’re responsible for is threatened with mining, and the urge to prevent it. Imagine the pain when it’s blown up and doesn’t exist in physical form anymore, just spirit and memory. Maybe you don’t need to imagine that – maybe you have tapped into that well of pain most of us are carrying in our ancestral roots. Maybe on your traditional lands, or like me, on lands you are spiritually adopting and feel are adopting you and your family too.

![]() If you value this content, please engage in reciprocity by living, sharing and giving.

If you value this content, please engage in reciprocity by living, sharing and giving.

Initiation

Blog by Valerie – hope you enjoy another book chapter!

Initiations are rites of passage ceremonies marking existential life transitions. An important one across Indigenous and Western cultures is the transition from spiritual child into spiritual adult. Abagusii scientist Mircea Eliade describes it thus:

To gain the right to be admitted among adults the adolescent has to pass a series of initiatory ordeals; it is by virtue of these rites, and by the revelations that they entail, that he will be recognised as a responsible member of the society. Initiation introduces the candidate into the human community and into the world of spiritual and cultural values. He learns not only the behaviour patterns, the techniques and the institutions of adults but also the sacred myths and traditions of the tribe, the names of the gods and the history of their works; above all he learns the mystical relations between the tribe and the Supernatural Beings as those relations were established at the beginning of Time[1].

Initiations intentionally lead us through Earth’s cycle from life into death then rebirth with a new identity through a purposefully traumatic process. (Image from here) As one Western psychologist explains:

Initiations intentionally lead us through Earth’s cycle from life into death then rebirth with a new identity through a purposefully traumatic process. (Image from here) As one Western psychologist explains:

The initiate, by virtue of encountering ritual trauma, was prepared to meet real-life trauma on terms that were integrative to the tribe’s social system and spiritual beliefs. Rather than encounter trauma as senseless and random, as many tend to do today, the initiate could meet trauma as an opportunity for meaningful participation with the greater spiritual powers[2].

Initiations may be seen as having three distinct phases: separation (from daily reality), ordeal (trauma), and return (rebirth and resolution)[3]. The separation phase tends to include seclusion from family and time in the wilderness to take us out of everyday familiarity into unknown energies and into encounters with the elements, spirits, and our non-human kin. (Image from here)

Initiations may be seen as having three distinct phases: separation (from daily reality), ordeal (trauma), and return (rebirth and resolution)[3]. The separation phase tends to include seclusion from family and time in the wilderness to take us out of everyday familiarity into unknown energies and into encounters with the elements, spirits, and our non-human kin. (Image from here)

In many Indigenous cultural traditions, men are put through painful initiation ordeals and women’s initiation is considered to be biologically built into the sacred ordeals of pregnancy and childbirth[4]. In some cultures, though, women are put through ordeals as well[5]. Spiritual initiations are painful because we tend to value what we earn through hard work, and we learn best through lived experiences.

Interestingly, a South Saami creation story[6] teaches that this entire world is the result of our previously taking the Earth’s bounty for granted and needing strong reminders of the value of her resources. This is similar to what I was told by some Mayan people in 2012 when the Western media was reporting that the Mayan calendar said the world was going to end. ‘No’, they told me, ‘our calendar says that in 2012 we are collectively moving out of spiritual childhood as a human species and into adolescence, and into a different calendar. They said overall we will become consciously aware that Mother Earth requires reciprocity, that we cannot just take from her, that there are consequences for our use of the Earth’s resources.

One example of an ordeal is the Sateré-Mawé tradition of adolescent boys enduring the pain of repeatedly putting their hand into a glove filled with bullet ants that inject toxins into them[7] (Image from here). They are called bullet ants because the intensity of the poison they inject is meant to hurt as much as being shot. The boys are expected to endure this willingly, silently and stoically, which teaches them be hunters who can handle the toughest aspects of their Amazonian jungle home; it also affirms values such as courage and strength. It also represents a loss of innocence by teaching that their environment can be dangerous, and even deadly, for after each session of placing a hand into the ant-ridden glove, boys are given medicine that makes them purge. Keeping the ant toxins in their body can have lifelong effects, such as loss of sanity. The myth is that the ants originate from the vagina of an underworld snake woman – an embodiment of the dark side of the sacred feminine and the Earth herself[8].

One example of an ordeal is the Sateré-Mawé tradition of adolescent boys enduring the pain of repeatedly putting their hand into a glove filled with bullet ants that inject toxins into them[7] (Image from here). They are called bullet ants because the intensity of the poison they inject is meant to hurt as much as being shot. The boys are expected to endure this willingly, silently and stoically, which teaches them be hunters who can handle the toughest aspects of their Amazonian jungle home; it also affirms values such as courage and strength. It also represents a loss of innocence by teaching that their environment can be dangerous, and even deadly, for after each session of placing a hand into the ant-ridden glove, boys are given medicine that makes them purge. Keeping the ant toxins in their body can have lifelong effects, such as loss of sanity. The myth is that the ants originate from the vagina of an underworld snake woman – an embodiment of the dark side of the sacred feminine and the Earth herself[8].

Initiations thus teach cultural myths and values, and ordeals without sacred spiritual stories attached to them are merely meaningless violence, reinforcing nihilism and lacking re-integration and fulfilment of a new identity along with its social responsibilities. In the example above, boys who complete the initiation are allowed to hunt and marry, which complete their rebirth as adult men in the community. Many of us grew up in cultures with rites of passage that included separation and ordeal phases but lacked full return phases to reintegrate us into a healthy new identity. We may feel called to question our cosmology and find a way to re-birth ourselves with limited collective ceremony or recognition of our hard work. (Image from here)

Initiations thus teach cultural myths and values, and ordeals without sacred spiritual stories attached to them are merely meaningless violence, reinforcing nihilism and lacking re-integration and fulfilment of a new identity along with its social responsibilities. In the example above, boys who complete the initiation are allowed to hunt and marry, which complete their rebirth as adult men in the community. Many of us grew up in cultures with rites of passage that included separation and ordeal phases but lacked full return phases to reintegrate us into a healthy new identity. We may feel called to question our cosmology and find a way to re-birth ourselves with limited collective ceremony or recognition of our hard work. (Image from here)

Exercise: What partial or full initiations have you been through? Were they facilitated by other people, or simply lived experience? If it was a full initiation, how do you celebrate your new identity? If it was a partial initiation, work with your ancestors and reflect how you may complete it to feel whole and celebrate your new identity.

![]() If you value this content, please engage in reciprocity by living, sharing and giving.

If you value this content, please engage in reciprocity by living, sharing and giving.

[1] Kenya, S.W. (2002). Rites of Passage, Old and New: The Role of Indigenous Initiation. In Thought and Practice in African Philosophy: Selected Papers from the Sixth Annual Conference of the International Society for African Philosophy and Studies (ISAPS) (Vol. 5, p. 191). Konrad-Adenauer Foundation. citing Mircea, Eliade., (1965) Rites and Symbols of Initiation, translation by W.R. Trask, New York; Harper and Row, pp x.

[2] Morrison, R. A. (2012). Trauma and Transformative Passage. International Journal of Transpersonal Studies, 31(1), p. 40.

[3] Id. citing Eliade, M. (1995). Rites and symbols of initiation: The mysteries of birth and rebirth. Woodstock, CT: Spring. (Original work published 1958)

[4] See e.g. Gonzales, P. (2012). Red medicine: Traditional Indigenous rites of birthing and healing. University of Arizona Press.

[5] See e.g. Dellenborg, L. (2009). From pain to virtue, clitoridectomy and other ordeals in the creation of a female person. Sida Studies, 24, 93-101.

[6] See Nordic Story Time: A South Sami Saami Creation Story, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UTDKeZB7rnM&list=WL&index=16&t=474s

[7] See e.g https://sites.google.com/fsmail.bradley.edu/buanthro/satere-mawe-ceremony

[8] Kapfhammer, W. (2012). Tending the Emperor’s Garden: Modes of Human-Nature Relations in the Cosmology of the Sateré-Mawé Indians of the Lower Amazon. RCC Perspectives, (5), 75-82.

Thanks-Giving at Solstice

Blog by Valerie

A few months ago somewhere in the outback around Broken Hill, I experienced a spiritual lightning strike inside. Something in me died, an old dream (maybe it was always a lie), and its energy has been emerging from my body in incredibly itchy rashes across my chest, back, face, and shoulders, and grief-laden tears. Sometimes I know certain things aren’t working but am reluctant to call them out or make a change, sitting in doubt and denial and dumbly hoping they’ll work out without conflict. I started to feel, for the first time in my life, like I could fully exist somewhere, and a community started to gently invite me in. Though it was not practical to join them, I can still see some smiles and hope and hear someone asking me to invite her to my housewarming when I move out there next year. It is possible. I’m sure I don’t know. All I know is the sand is shifting under my feet again, and some people and aspects of life I’ve been counting on are disappearing. I’ve been through this many times, and I know my role is to stay centred, be patient, accept the gifts I’m given, let go of that which is not working, and freefall into the unknown with as much grace as I can.

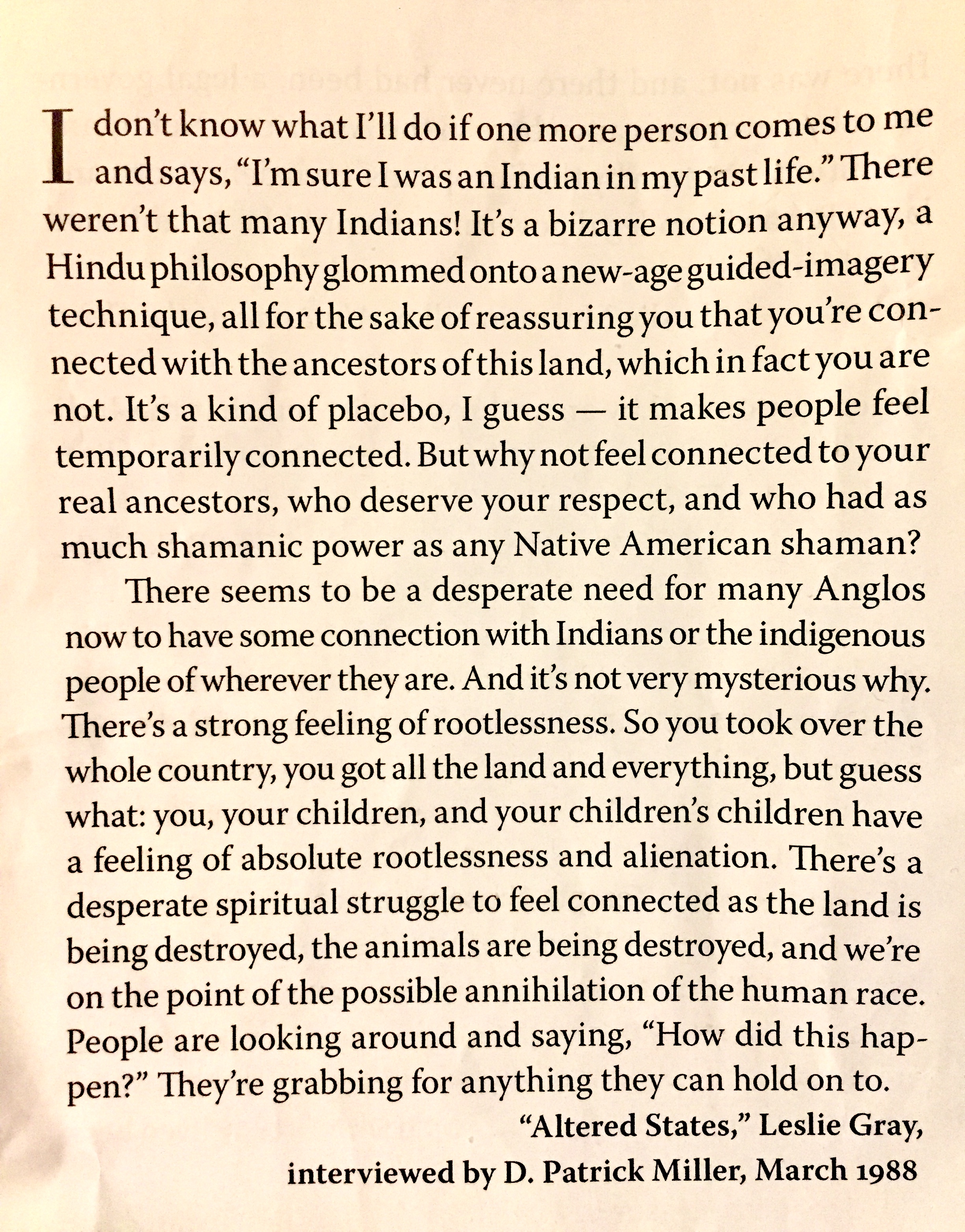

Though much trauma is being acted out in the world right now that is sometimes referred to as ‘white privilege,’ no one is merely ‘white’, and I cringe when I am referred to as such. We all have cultural heritage with gifts to unpack and celebrate. My modern, multi-cultural self includes a body born of Shawnee land carrying earth ethos teachings from my East Frisian roots as well as teachings about existential destruction from my Ashkenazi Jewish lineage, as well as wisdom from Native American, Anglo-Celtic Australian, Anglo-Saxon American, Irish-American, Hispanic-American, African-American, Asian-American, Peruvian, Indian, South African, Buddhist, Christian, Hindi, Aboriginal, and many other beautiful cultures. I saw a quote a few months ago that really resonated and went something like this:

Though much trauma is being acted out in the world right now that is sometimes referred to as ‘white privilege,’ no one is merely ‘white’, and I cringe when I am referred to as such. We all have cultural heritage with gifts to unpack and celebrate. My modern, multi-cultural self includes a body born of Shawnee land carrying earth ethos teachings from my East Frisian roots as well as teachings about existential destruction from my Ashkenazi Jewish lineage, as well as wisdom from Native American, Anglo-Celtic Australian, Anglo-Saxon American, Irish-American, Hispanic-American, African-American, Asian-American, Peruvian, Indian, South African, Buddhist, Christian, Hindi, Aboriginal, and many other beautiful cultures. I saw a quote a few months ago that really resonated and went something like this:

Life was better before colonisation and mass migration, but now it is more beautiful.

I think there is much truth in that, as well as the inset quote a friend sent me. We each have much to celebrate and reconcile within our individual cultural mix. So on December 24, I finished baking some Stollen, sang Godewind songs in German and Platt, told stories and looked at photos to honour my East Frisian paternal ancestors and country.

To honour my earth ethos, I celebrated a fiery summer solstice in ceremony with loved ones. (Literally, there were, and are, many fires burning this country.) Sitting around a fire pit in the four directions, we embodied some of my heart’s favourite forms of expression: music, meditation, poetry, and art. Part of our ceremony was a poetic prayer in words & drumming to the Thanksgiving Address gifted to us all by the Haudenosaunee, which brings our minds together as one in thanks for: The people, The Earth Mother, The Waters, The Fish and Other Water Creatures, the Plants, The Food Plants, The Medicine Herbs, The Animals and Insects, The Trees, The Birds and Other Air Creatures, The Winds, The Thunder Beings, Grandfather Sun, Grandmother Moon, The Stars, The Wise Teachers, The Creator, and All Others Who Have Not Been Named. (Image from here of the People thanking Grandmother Moon)

To honour my earth ethos, I celebrated a fiery summer solstice in ceremony with loved ones. (Literally, there were, and are, many fires burning this country.) Sitting around a fire pit in the four directions, we embodied some of my heart’s favourite forms of expression: music, meditation, poetry, and art. Part of our ceremony was a poetic prayer in words & drumming to the Thanksgiving Address gifted to us all by the Haudenosaunee, which brings our minds together as one in thanks for: The people, The Earth Mother, The Waters, The Fish and Other Water Creatures, the Plants, The Food Plants, The Medicine Herbs, The Animals and Insects, The Trees, The Birds and Other Air Creatures, The Winds, The Thunder Beings, Grandfather Sun, Grandmother Moon, The Stars, The Wise Teachers, The Creator, and All Others Who Have Not Been Named. (Image from here of the People thanking Grandmother Moon)

May you enjoy the blessings of the season from Father Sun and Mother Earth whether you have just been through Summer or Winter Solstice.

![]() If you value this content, please engage in reciprocity by living, sharing and giving.

If you value this content, please engage in reciprocity by living, sharing and giving.