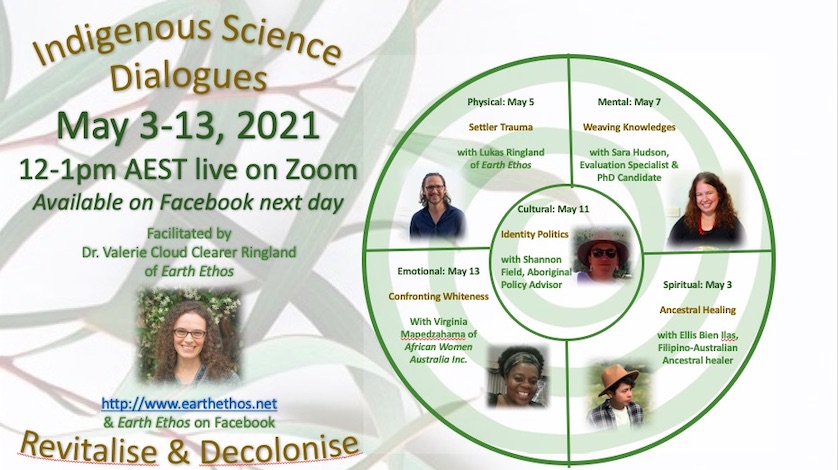

Long Blog by Lukas

I suffered brutal bullying in high school. I also acted as a perpetrator. And a bystander. Sitting on all sides of this equation is perhaps the hardest role of all. There are many anecdotes I could tell but one stands out, because it was an encounter with traumatic evil, and perhaps more than any other moment in my adolescence, marked the loss of my childhood innocence.

***Trigger warning: bullying story. To skip the story, scroll below to the next *** for reflections.

It was school camp 1998. Year 8. I was 13. My bullying experience at the hands of my so-called circle of friends had been slowly gathering pace. But there’s only so much that can be done in the hours of a school day. School camp was going to be a different beast.

Sensitivity and my steely sense of fairness and justice are amongst my greatest gifts, but like many such things, are a source of great vulnerability. I used to liken myself to a ripe peach. Not only did I bruise easily, but it showed so very obviously. Yet I never got squashed entirely. At my core I have a rock hard seed that doesn’t break. This gave my tormenters a sense of sport. Even the most sociopathic of people seem to tire of picking on something completely broken and pathetic.

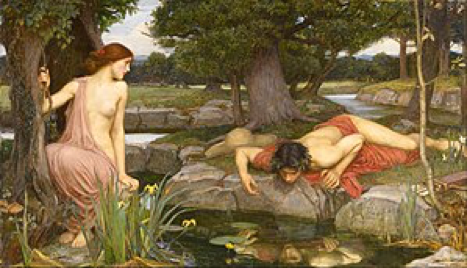

In the days leading up to camp, a number of boys within my ‘friendship’ group had begun to use the word “core” and “non core” to describe members of the group. Core members received privileges, and non-core members were made to feel lesser than and ostracised from certain activities. I was “non core,” and it got to me, and they could tell. By then I had a number of nicknames that I hated too, not because they were particularly harmful, just the condescension of it all. We were meant to be friends. There was also a very dark and (as I experienced it) deeply shameful (though in hindsight, completely innocent) rumour of a sexual nature that had followed me all the way from early primary school that lurked in the background. Such was the power of the shame over me that they only needed to threaten to use it to crush all resistance I might have offered. Call this the nuclear deterrent. (Image from here)

Even at 13 years old, I feel like I had some responsibility for not exiting this group earlier. But even to this day I have a tendency to let things run their course in social dynamics even when it’s clear they’re not healthy. I call this my “crash the plane into the mountain instead of jump out with a parachute” mentality. It’s something to work on. And run its course it did, a crash course with the mountain of school camp.

It didn’t take long. A long bus ride filled with put-downs and taunts was followed by the announcement that only “core” group members could keep their bags inside the tent. There was also the “core” clothes line. I’d had enough. With a barrage of insults fired back in their direction, I announced that I was done with them. I made a deal with another brutally bullied chap who wanted to be in this social group to swap tents. I had no sympathy for him.

It was well and truly on. I had challenged their power publicly. The “nuclear deterrent” was armed and readied for use. Sexually based taunts have a particular sting to them, perhaps because we are so apt to feel shame in that area, such are our deeply socialised taboos. I tried to show my face at the campfire – as one wants to do at a camping trip – but the put downs were unrelenting. I had no defense, no come back. I ran back to my tent, tears streaming down my face. Beaten. Broken.

But worse was to come.

I wrapped myself up tight in my sleeping back and sobbed. It was not performative in the slightest, and was to my knowledge, private. But no.

All of a sudden I felt a deep pain in my back. Someone or multiple someones had followed me back from the campfire and had kicked me, hard, through the tent. I let out a wail and some kind of “f*** you”. Insults given amongst sobs are not that intimidating though. A few seconds went by. I wondered if that indignity would be the end of it. But no. A second kick, even more painful.

This time I let out a guttural howl of rage, and emerged from the tent. I didn’t see my offenders so I ran over to their tent and jumped on it with all my weight. As one of those boys used to just love recounting in the weeks afterwards, it was one of those tents with the springy poles that as soon as I got back to my feet, just popped back into shape as though I was never there. Never there. That was about right.

My chief tormentor – the de facto head of the group – emerged from their tent. I don’t think he was one of my kick attackers, but I didn’t care. I punched him square in the face with all my might – just the thing to fix a bully according to my dad and just about all popular culture. He was briefly startled and began backing away. I shouted at him to fight me. I’ll never forget the way the expression changed on his face: from surprise, to alarm, to a brief flicker of readiness to fight and then..a smirk…and a headshake. He then turned his back on me and walked away. Clever.

With that gesture of profound condescension, he won. Did I proceed to keep beating him, to have my fight whether he was going to show up or not? No I did not. And this haunted me – perhaps I might even say crippled me, though in truth this incident was but one of many – for years. Decades. Perhaps it still does.

I spent the following days feeling and playing dead. There was more to the bullying even on that trip, much more, but I’ll leave it there.

I did not tell an adult, the teachers. But I looked them searchingly in the eye. Perhaps I was asking myself “could, or should, I tell them?”. But no. I got the feeling they didn’t like me. One of them – the Deputy Principal in fact – actually and literally told one of my bullies that he didn’t like me. I don’t remember how I found that out. Perhaps it was because the previous year I’d been in his office for reasons of bullying on the offender side, and thus deserved it? Little did he know how much our thoughts were aligned, and how damaging this was to me.

***

I was never, and could never be, the same person again after this and many other experiences like it around that time. Leaving childhood behind forever is of course a natural and desirable outcome of adolescence. But the vehicle for my passage, my initiation, my ordeal, was evil. This is so far from the intentional, ceremonial, sacred and mediated by responsible elders kind of initiation that is practiced by wise cultures. It was trauma without much meaning beyond developing an intimacy with evil. But it was an evil I could not name, such was my deep belief that it was my deep personal failings that brought it upon myself. (Image from here)

In writing this, my ordeal sounds very alike the relationship between the Church and the people in medieval Europe. Don’t focus on the wrong of having your Indigenous culture genocided, pray for your forgiveness for your innate sinfulness.

Our deep patterns reverberate until something more powerful intervenes. For me, it has been having my adult life and the whole identity I was raised with fall apart. It’s like I’ve had to do my right of passage over again, but scarred, burdened and traumatised by the experience of the first, and, weighted down by the intergenerational trauma of my ancestors that I not only carry personally, but that which is literally built into the social and systemic structure of the society in which I was raised and still live.

Evil is a rather heavy hitting word. So much so that many modern social theorists reject it entirely, instead wanting to focus on pathological or environmental causes of harmful human behaviour. These perspectives are valuable, but to strip evil from our cultural lexicon is to reduce our ability to describe an experience of profound malevolence. (Image from here)

I think the aversion to ‘evil’ has more to do with a modern desire to have a common moral and ethical understanding of the world devoid of the spiritual. This is one of the many bad marriages between Western pluralistic liberalism and logical positivism. This is to say firstly, the belief that single sovereign entities (as opposed to confederations of sovereign entities) can hold and treat equally people with a diversity of spiritual beliefs, and that secondly, the rules and practices that govern such a culture can and should be based in concretely knowable moral and ethical truths that everyone can agree on.

In fairness to this way of thinking, much harm has been done under the guise of eliminating evil. Top down, coercive and dominating control of spiritual knowledge and life from religious institutions deeply abused the idea that there is an existential evil in the universe that should be eliminated at all costs. Attaching ‘existential’ to evil is deeply problematic (more on this later), and obviously even more so when wielded by those deeply beset by Wetiko.

But regardless, in my view, to live fully as humans I believe it essential to experience life at the level of the spiritual. In this I’m talking about that which is experienced outside of rationally expressed conceptual reason; that which gives life a lot of its meaning.

A sense of spiritual awe is never more important than when looking for ways to deal constructively with and making sense of profound suffering, pain and trauma. We need to be able to distinguish between the deeply painful in raw form, the tragic, and evil. I think this is why so many cultures “get out in front of it” so to speak, and intentionally inflict pain and ordeal upon people in the form of initiation. People need discernment in this area of life perhaps as much or more than any other. We need to see and be able to hold and make sense of the light, the dark and everything in between. (Image from here)

So like many, many things that have occurred as societies move on from Judeo-Christianity, the notion of evil is absolutely one of the babies that should not be tossed out with that bathwater.

Most people understand that suffering, pain and trauma are not synonymous with darkness and the shadow (though abusing our almost primal propensity to want to avoid it is a tremendously effective way to enslave people without their knowing it). They have a shadow, and can exist in shadow, but they are not intrinsically so. We experience them, and it is the quality of this experience that gives them their character. So they are definitely not evil, but they certainly can be expressed and experienced as so.

So what is evil?

Controversial Western psychologist Jordan Peterson has written and spoken a lot on the topic, and whatever you may think of his politics, I think what he has to say on this topic is valuable. He draws a very sharp distinction (perhaps overly so) between evil and tragedy.

The truly evil, he says, possesses a “demonically warped aesthetic”. After thinking about this for a while, I came up with my own version: “volitionally malevolent aesthetic”. I had to ruminate on what he means by “aesthetic” here, and I think he’s saying that part of a human action that comes from expression and taste, largely disconnected from practical necessity. When this expression is designed to cause extra suffering, that’s evil. Like a desire to manifest with free will and volition the polar opposite of beauty. It’s like he’s saying evil is almost like a kind of dark artistry.

Some of his examples are very very dark, such as the “work sets you free” sign on the gates of Auschwitz. This was not a work camp, but an expressly designed death camp. It was a deliberate torment. Evil upon evil. Something dark for the tormentors to enjoy.

When I think about my bullies, I think about the choice of things that they could have done to me. They chose things for maximum hurt, yes, a practical wielding of power. But the decision to kick me in the back whilst I lay sobbing in my tent, was an expression of some kind of dark…aesthetic. It was mostly unnecessary in a practical hierarchical sense. I was already beaten. It was about giving the whole affair a certain sadistic panache; an evil cherry on top.

The use of the word “demon” is interesting. Within Christianity it is used existentially. The devil is evil, and will always be thus, as a more or less cosmological fact. And so given his Christian sympathies, I am suspicious of Peterson here. So to me it proved interesting to look up the etymology of demon. (Image of Pazuzu, a Mesopotamian demon Valerie has seen in a number of visions and found to be helpful)

In its earlier usage, Demons were seemingly not originally nor wholly, existentially bad or dark. It was behaviour that was so. In most indigenous cultures, their darker characters or malevolent spirits are more teaching tools that everyone can learn from. Collections of energies that serve to remind all of us of the darker tendencies that we need to watch out for in our own selves. As spirit beings and helpers, there are more shades of gray, and less taboo. Perhaps this is what modern social theorists want to achieve when they focus on the environmental and social factors behind dark acts, rather than the physical or spiritual pathology. But I do believe we need to work with evil as a teaching tool, to help us see what we’re capable of, learn to avoid it, and process its meaning constructively. Because it does exist, like it or not, and if we pretend it doesn’t, I’m with the Christian perspective that “the greatest trick the devil ever pulled was convincing the world he didn’t exist”. I think denying evil’s existence will be to our severe detriment.

For me, deriving constructive meaning from my experience of evil has been largely about breaking my attachment to a culture that fostered and tolerated the behaviour on the one hand, and in other circumstances, punishes those who do evil with more evil. This, I think, was the mentality of the Deputy Principal who thought I “deserved” to be abused. Like jail in most countries, which makes an almost science out of doing evil onto those accused of doing evil (though I suspect jails contain more people whose crimes are better described as more tragic than evil).

With more space from modern Western society, I feel more free to access and develop healthier understandings of myself and the universe that situates evil in a more balanced perspective and context.

Exercise: Reflect when and where you feel you have encountered evil. Have you been able to process it in a way that felt constructive? Consider re-visiting one such encounter using an altered state tool such as meditation with the intention of reframing the meaning of your experience.

![]() If you value this content, please engage in reciprocity by living, sharing and giving.

If you value this content, please engage in reciprocity by living, sharing and giving.

For me it has been vital to live in two worlds: (1) a social reality that is based on a Western worldview, and (2) an earth-based reality based on an Indigenous worldview. When I’m caught up in a survival struggle in the Western world that’s terrifyingly real, and I’m feeling rejected and judged and shamed and angry, I can spiritually connect with the knowing from the Land and my ancestors that I’m not only allowed to exist but that I am wanted. This powerful medicine is all I have found that alleviates my existential wounds. Without it I feel like I would not still be here on this Earth, as my roots would have rotted and not been able to hold up the rest of my inner tree of life. (Image from

For me it has been vital to live in two worlds: (1) a social reality that is based on a Western worldview, and (2) an earth-based reality based on an Indigenous worldview. When I’m caught up in a survival struggle in the Western world that’s terrifyingly real, and I’m feeling rejected and judged and shamed and angry, I can spiritually connect with the knowing from the Land and my ancestors that I’m not only allowed to exist but that I am wanted. This powerful medicine is all I have found that alleviates my existential wounds. Without it I feel like I would not still be here on this Earth, as my roots would have rotted and not been able to hold up the rest of my inner tree of life. (Image from

Altering my consciousness is another survival tool I use daily, primarily through

Altering my consciousness is another survival tool I use daily, primarily through  ‘We are cycles of time’ stuck in my head after reading a

‘We are cycles of time’ stuck in my head after reading a  So it’s fair to say that I have seen plenty of intergenerational trauma playing out in mine and other people’s lives. It’s particularly humbling to see it play out now, as a mother with my baby. But once I realize that’s what’s happening, I know we will have to ride this

So it’s fair to say that I have seen plenty of intergenerational trauma playing out in mine and other people’s lives. It’s particularly humbling to see it play out now, as a mother with my baby. But once I realize that’s what’s happening, I know we will have to ride this  I have felt a lot of grief that so much of my energy in the pregnancy and birth, and even as a young mother now, is about processing trauma and grief instead of just being in the moment enjoying my baby. Though I feel nervous about looking for housing, packing and moving, I realize we’re all a cycle in time. And though it’s tough, my role now is to process as much trauma and ground as much nervous energy as I can so my baby has more opportunity to be present with their child in the next cycle.

I have felt a lot of grief that so much of my energy in the pregnancy and birth, and even as a young mother now, is about processing trauma and grief instead of just being in the moment enjoying my baby. Though I feel nervous about looking for housing, packing and moving, I realize we’re all a cycle in time. And though it’s tough, my role now is to process as much trauma and ground as much nervous energy as I can so my baby has more opportunity to be present with their child in the next cycle.

Trauma’s meaning, causes and methods of healing differ by culture and

Trauma’s meaning, causes and methods of healing differ by culture and  Reconnecting to the Earth

Reconnecting to the Earth Our task as healers is to allow alchemy to occur so that sh*t we are carrying in our hearts, minds, bodies and spirits can instead turn into fertiliser for ourselves and others. By consciously choosing to move into terror and aversion/disgust when we are in a safe space, we can reconnect with lost soul parts. In doing so, we gain knowledge that expands our individual and collective understanding of ourselves and our world. This is seen as the sacred calling underlying a ‘shaman’s illness’. Trauma is seen as a spiritual offering of a huge amount of energy that can redirect us into a new identity like a phoenix rising out of ashes. Indigenous healers are called ‘medicine people’ or ‘shamans’ because through healing trauma we embody medicine by living in a wiser way and offering support to others who are struggling through similar wounds.

Our task as healers is to allow alchemy to occur so that sh*t we are carrying in our hearts, minds, bodies and spirits can instead turn into fertiliser for ourselves and others. By consciously choosing to move into terror and aversion/disgust when we are in a safe space, we can reconnect with lost soul parts. In doing so, we gain knowledge that expands our individual and collective understanding of ourselves and our world. This is seen as the sacred calling underlying a ‘shaman’s illness’. Trauma is seen as a spiritual offering of a huge amount of energy that can redirect us into a new identity like a phoenix rising out of ashes. Indigenous healers are called ‘medicine people’ or ‘shamans’ because through healing trauma we embody medicine by living in a wiser way and offering support to others who are struggling through similar wounds. The dialogue of that name was with my friend

The dialogue of that name was with my friend

Shona (Zimbabwean) Australian woman

Shona (Zimbabwean) Australian woman  This “mere existence” of Aboriginal people as humans worthy of dignity collapses the entire ‘legal’ foundation of the Australian nation. The High Court overturned

This “mere existence” of Aboriginal people as humans worthy of dignity collapses the entire ‘legal’ foundation of the Australian nation. The High Court overturned  When I hear

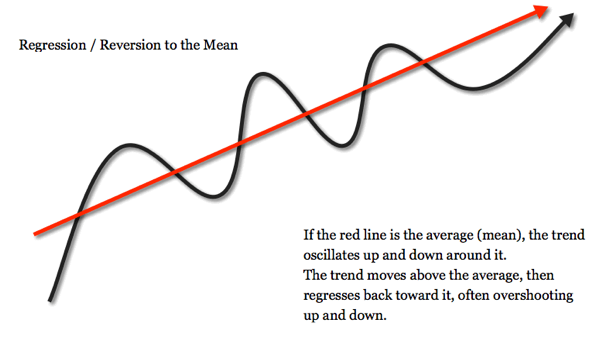

When I hear  In social environments, it seems to feel proportionally less safe to be oneself the farther we identify from collective norms and ideals. There is a concept in mathematics called ‘regression to the mean’. It is basically the idea that when you put some ice into a glass of water, the ice will tend to melt and take the form of the water; in essence, it is about assimilating into a collective norm. Yet assimilation is a dirty word for many people, because we want to celebrate our uniqueness as well as being part of a peoples. (Image from

In social environments, it seems to feel proportionally less safe to be oneself the farther we identify from collective norms and ideals. There is a concept in mathematics called ‘regression to the mean’. It is basically the idea that when you put some ice into a glass of water, the ice will tend to melt and take the form of the water; in essence, it is about assimilating into a collective norm. Yet assimilation is a dirty word for many people, because we want to celebrate our uniqueness as well as being part of a peoples. (Image from  Feeling safe to celebrate our difference depends on culture and context. These social wounds keep us trapped and unable to trust ourselves, each other, non-humans, and Spirit/God/oneness. Our capacities to heal and seek retribution are also based on cultural values and intergenerational traumas. Cultures that are more welcoming of outsiders seem to encourage healing and embracing collective wounds for transformation, whereas cultures that are more exclusionary seem to ‘other’ people and tend towards separation and seeking retribution. Fear of retribution can keep us trapped and unable to trust. It is as if there is a collective trauma belief that says, ‘if we let them in, they will hurt us.’ In my experience with Judaism, and what I am learning are my deeper Sumerian cultural roots, there seems to be a collective belief that ‘we can’t trust anybody.’ My own grandmother told me that as a child, and I asked her incredulously if I couldn’t even trust her. She didn’t answer, just stared at me in silence. Living in this social environment, I never felt safe. In fact, I felt terrified to even take up space. One wrong move could find me terribly punished, kicked out of the group, or worse, judged irredeemable by God. Despite constantly striving to be ‘a good person’, it never felt like what I did was good enough. I got used to feeling terrified that threats of judgment, punishment and retribution were always imminent. I worked hard to learn the rules I might break and the triggers I might set off that would result in my being punished. But I wasn’t in control. My brother had a habit of breaking rules and refusing to admit it, so we would both be punished. This was scary, too, because I didn’t know when the punishment would happen, or how intense it would. It felt safer at times to intensely control and punish myself so that I maintained a sense of autonomy. It also seemed safest to play the part of

Feeling safe to celebrate our difference depends on culture and context. These social wounds keep us trapped and unable to trust ourselves, each other, non-humans, and Spirit/God/oneness. Our capacities to heal and seek retribution are also based on cultural values and intergenerational traumas. Cultures that are more welcoming of outsiders seem to encourage healing and embracing collective wounds for transformation, whereas cultures that are more exclusionary seem to ‘other’ people and tend towards separation and seeking retribution. Fear of retribution can keep us trapped and unable to trust. It is as if there is a collective trauma belief that says, ‘if we let them in, they will hurt us.’ In my experience with Judaism, and what I am learning are my deeper Sumerian cultural roots, there seems to be a collective belief that ‘we can’t trust anybody.’ My own grandmother told me that as a child, and I asked her incredulously if I couldn’t even trust her. She didn’t answer, just stared at me in silence. Living in this social environment, I never felt safe. In fact, I felt terrified to even take up space. One wrong move could find me terribly punished, kicked out of the group, or worse, judged irredeemable by God. Despite constantly striving to be ‘a good person’, it never felt like what I did was good enough. I got used to feeling terrified that threats of judgment, punishment and retribution were always imminent. I worked hard to learn the rules I might break and the triggers I might set off that would result in my being punished. But I wasn’t in control. My brother had a habit of breaking rules and refusing to admit it, so we would both be punished. This was scary, too, because I didn’t know when the punishment would happen, or how intense it would. It felt safer at times to intensely control and punish myself so that I maintained a sense of autonomy. It also seemed safest to play the part of  For most of my life I felt terrified to take up space. I felt like no space was ‘mine’ existentially or practically. For example, growing up, I wasn’t allowed to lock my bedroom door. I used to get dressed in my walk-in closet so I had some privacy and warning if my mother was coming into my bedroom. It took many years into adulthood – and practically ending many formational familial relationships that were untrustworthy just as my grandmother had told me – for me to become trustworthy to myself, be authentic and celebrate my difference, and surround myself with trustworthy and authentic people. By trustworthy, I mean people who say what they mean and do what they say, and when they can’t follow through on something, own it, apologise, forgive themselves, and make amends if needed. By authentic, I mean people who know their core values and practice embodying them in everyday life.

For most of my life I felt terrified to take up space. I felt like no space was ‘mine’ existentially or practically. For example, growing up, I wasn’t allowed to lock my bedroom door. I used to get dressed in my walk-in closet so I had some privacy and warning if my mother was coming into my bedroom. It took many years into adulthood – and practically ending many formational familial relationships that were untrustworthy just as my grandmother had told me – for me to become trustworthy to myself, be authentic and celebrate my difference, and surround myself with trustworthy and authentic people. By trustworthy, I mean people who say what they mean and do what they say, and when they can’t follow through on something, own it, apologise, forgive themselves, and make amends if needed. By authentic, I mean people who know their core values and practice embodying them in everyday life. It is still unsafe for me in many spaces where my values conflict with the collective. But I don’t feel a need to constantly strive towards some central ideal, nor do I feel like it’s me against the world at war. I feel peace in myself for accepting who I am and doing my best to navigate the collective morass, and for cultivating spaces where I, and others, are free to be. In this way, I can embody the knowing that we are enough. (Or ‘good enough’, whatever that means.) (Image from

It is still unsafe for me in many spaces where my values conflict with the collective. But I don’t feel a need to constantly strive towards some central ideal, nor do I feel like it’s me against the world at war. I feel peace in myself for accepting who I am and doing my best to navigate the collective morass, and for cultivating spaces where I, and others, are free to be. In this way, I can embody the knowing that we are enough. (Or ‘good enough’, whatever that means.) (Image from