Blog by Lukas

There are many different ways to reflect upon the tumult of world right now. Indeed, the very sense that things are particularly tumultuous is in some ways a mirage, and like all mirages, is born of perspective.

Reflecting to a fellow millennial about the relative tranquility of the 1990s of my childhood, it didn’t take long to think of some examples that demonstrate the extent to which this was not true for everyone. The Rwandan genocide and the war in the Balkans immediately came to mind, as well as famine in Somalia, the Oklahoma City, Port Arthur, the Japanese death cult that released nerve gas on the subway. The 90s weren’t really that tranquil.

But like all things that feel deeply true, and therefore should not be dismissed outright, I can’t ignore the sense that there is something different about this moment in time. I think this is especially so for those of us who live in the Western world, but if we expand that out to people deeply impacted by the goings on in Western world, it seems pretty clear that everyone is affected to one degree or another.

But like all things that feel deeply true, and therefore should not be dismissed outright, I can’t ignore the sense that there is something different about this moment in time. I think this is especially so for those of us who live in the Western world, but if we expand that out to people deeply impacted by the goings on in Western world, it seems pretty clear that everyone is affected to one degree or another.

The key to making sense of all of this might be to open ourselves to the possibility or multiple truths, dualities and both/ands. This may need intentional nudging given that most of us have been socialised to believe in one overriding and logically derived ‘truth.’

Perhaps we can simply say that things are different, but also the same. In Indigenous science, the practicality of this might hinge on where we are, who we’re talking to or what we’re focusing on. In other words, truth as something fluid, and relational. Or it could just be a duality.

So what IS different about this moment?

Of late, I’ve been struck by the extent to which so many of the problems in the world can be put down to poor or unwise leadership, and by extension (though I’m not sure in which direction this flows), real eldership.

Bad leadership is of course not new. It is so not new that many people speaking from a modern perspective utterly saturated in bad leadership for hundreds of years, argue that it is more or less innate and inevitable. Such a perspective sees greed as omnipresent, force as the strongest power, and power inherently leading to domination and corruption. I cannot stress how wrongheaded and unwise these kinds of maximalist perspectives are in my opinion, but suffice to say, I do see it as useful to see this darkness as an inevitable part of human nature.

The potential to play host to the psycho-spiritual virus of greed (beautiful elucidated as a concept called Wetiko/Windigo in some Native American cultures ) and putting one’s own needs too far above those of fellow humans (and ultimately, the planet), is clearly endemic, and in a sense, a permanent potentiality of the human shadow. But it does not have to be so dominant as it is at present. Many cultures knew and understood this, and created environments to fortify against it by actively nurturing and fostering wiser ways of living (including of course good leadership), and also creating taboos that served to suppress it.

So again, what’s different about now compared with recent history? I feel the need to answer that question with other questions:

To what extent do the performative aspects of good leadership actually mean better leadership and less Wetiko? And is it better to have the symptoms and impact of bad leadership show themselves more subtlety and insidiously, inviting more trickery and deception into our lives, or is it better to have things boil over and fester openly, destructively and chaotically?

Here are two stark examples of these ways of being: the US President sending the Secretary of State to the UN Security Council to make the case for the 2003 Invasion of Iraq (and then doing it anyway when they said no) versus the US President not bothering with anything of the kind before taking the President of Venezuela; Israeli leaders throughout most of its history officially espousing a two state solution to the ongoing violence (even when actions belied this intention) versus the current Israeli Prime Minister declaring his open hostility to the idea, and arguably therefore, any hope of peace or freedom and self determination for Palestinians.

To me, of the many concepts that we can use as an easy synonym for ‘wise leadership’, the simple act of being graceful during hard times, especially with rivals or people who threaten you, is one of the better ones.

Grace is defined in the dictionary in two main ways:

-

- smoothness and elegance of movement, and

- courteous good will.

Its proto Indo European deep root is *gʷerH (don’t ask me to decode that!) and relates to praise and welcome. The possibilities for a rich tapestry of wise leadership and eldership under such a concept are profound. It means responding, not reacting. Welcoming not just people, but events, which means not rejecting things existentially. It means being grateful for hard things, not just easy things.

But back to the question. How much does what I’m going to call ‘performative grace’ indicate real grace, and how much do we need it?

To start with, ‘performative grace’ is on a continuum. Not as good as something more real, substantive and completely embodied, but meaningful, and better than no attempt at grace. And of course, we need to be on the lookout for genuine intentions versus pure trickery. Trying to do better versus merely pretending to care.

When the current US President was elected for the second time, I chided someone I know for saying “he’s no worse” than the other candidate. I had the benefit of a close up perspective of life in the United States as a social worker and knew that many vulnerable people were about to suffer even more.

But reflecting now, I think even beyond the direct impact of destructive actions, there is a clear difference between current leadership and what has come before in terms of the intention, or performance, of grace. And this matters.

To me it is clear that even a pretence of grace results in less short term suffering. The mechanisms for this are too innumerable and complex to be fully explained rationally. We just know it when we experience its impact, including in our own individual lives. Intention is an impactful force in and of itself.

So the more grace embodied in our leadership, even if it’s mostly intentional, the less short term suffering there’ll be in the world. But it’s beneath us — beneath our potential — to be forever stuck at only performative grace. Perhaps we need the most toxic and graceless leadership elements in our midst to dominate for a while in order to expose more vividly those blocks stopping us from having leaders that genuinely embody grace more fully.

We can grieve that we will all be hurt by this, and at the same time we must not only grieve, but allow ourselves the natural instinct of struggle to make things better right now. This might mean settling for genuine performative grace if that’s truly the best we can do. It often feels like the best I can do in my own individual life, with my own self-leadership, as depressing as that may feel.

However difficult, holding the paradox that we can both accept the need for harsh medicine whilst also striving to ease suffering along the journey is an important spiritual skill, for any person, culture or society.

Reflection: How can we be better at accepting where we’re at whilst also aiming for better, all from a place of grace?

![]() If you value this content, please engage in reciprocity by living, sharing and giving.

If you value this content, please engage in reciprocity by living, sharing and giving.

I recently came across the concepts of clean and dirty pain. This is a well written

I recently came across the concepts of clean and dirty pain. This is a well written

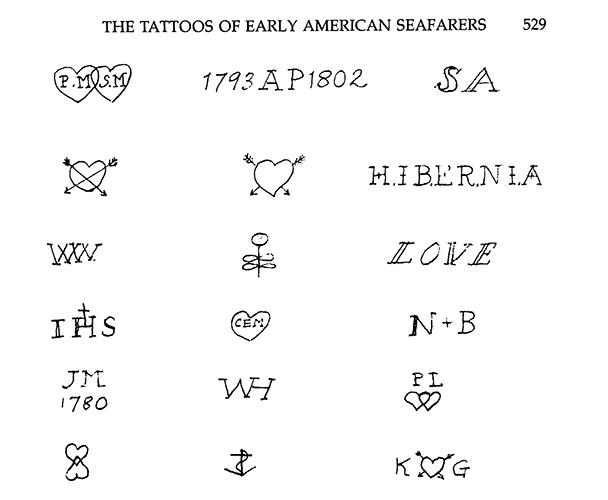

modern day Ukraine and Romania, and a 5000 year old mummy found preserved in ice in the Italian Alps who appears to have therapeutic tattoos in places on his body that look similar to a practice in traditional Asian cultural medicines. Such tattoos tend to be at joints and in the lower back. Tattooed mummies have also been found from Egypt to Siberia to Peru, and tattooed earthenwares of human or spirit figures have been found across the world from ancient Mississippi to Japan to the Philippines.

modern day Ukraine and Romania, and a 5000 year old mummy found preserved in ice in the Italian Alps who appears to have therapeutic tattoos in places on his body that look similar to a practice in traditional Asian cultural medicines. Such tattoos tend to be at joints and in the lower back. Tattooed mummies have also been found from Egypt to Siberia to Peru, and tattooed earthenwares of human or spirit figures have been found across the world from ancient Mississippi to Japan to the Philippines.  The word ‘tattoo’ was brought into English from James Cook’s 1770s journey to New Zealand and Tahiti, and supposedly inspired Western sailors to start a tradition of tattooing themselves to remember where they had traveled and people they missed at home. (Image of a Ta`avaha (headdress) with tattoos, Marquesas Islands, 1800s, via Te Papa from

The word ‘tattoo’ was brought into English from James Cook’s 1770s journey to New Zealand and Tahiti, and supposedly inspired Western sailors to start a tradition of tattooing themselves to remember where they had traveled and people they missed at home. (Image of a Ta`avaha (headdress) with tattoos, Marquesas Islands, 1800s, via Te Papa from  And while I can’t speak for how locals feel about Angelina’s tattoos (she was given

And while I can’t speak for how locals feel about Angelina’s tattoos (she was given  Western culture. I remember a trend some years ago of getting Chinese characters tattooed without many people even knowing or speaking the language. (I used to wonder how people weren’t scared they were lied to about what their tattoo said!) And many modern designs in Western culture have originated from those early sailors’ tattoos in the 1700s and 1800s. However, many have not, and where some celebrities like Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson express Samoan heritage through tattoos, others like Mike Tyson who is not of Maori descent has a ta moko design on his face (See

Western culture. I remember a trend some years ago of getting Chinese characters tattooed without many people even knowing or speaking the language. (I used to wonder how people weren’t scared they were lied to about what their tattoo said!) And many modern designs in Western culture have originated from those early sailors’ tattoos in the 1700s and 1800s. However, many have not, and where some celebrities like Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson express Samoan heritage through tattoos, others like Mike Tyson who is not of Maori descent has a ta moko design on his face (See  In an Indigenous worldview, the mother is seen as a conduit between the spiritual and physical worlds, and birthing

In an Indigenous worldview, the mother is seen as a conduit between the spiritual and physical worlds, and birthing  There are of course many cultural variations on such ceremonies. One example is in parts of India where there is a sort of baby shower called a

There are of course many cultural variations on such ceremonies. One example is in parts of India where there is a sort of baby shower called a  There are also many cultural variations for these ceremonies. For example, in Japan

There are also many cultural variations for these ceremonies. For example, in Japan  A sweet example of such a ceremony comes from the Navajo/Diné people of North America have a ceremony to honour the babies’ first laugh, and the person who gets the baby to laugh throws a party where guests are given salt on the baby’s behalf as a symbol of generosity since it was traditionally valuable and hard to get (Brown, Shane. (2021). Why Navajos Celebrate the First Laugh of a Baby.

A sweet example of such a ceremony comes from the Navajo/Diné people of North America have a ceremony to honour the babies’ first laugh, and the person who gets the baby to laugh throws a party where guests are given salt on the baby’s behalf as a symbol of generosity since it was traditionally valuable and hard to get (Brown, Shane. (2021). Why Navajos Celebrate the First Laugh of a Baby.  Placental ceremonies are based on traditional understandings of the placenta as a spiritual twin, a baby’s guardian angel, a ‘death’ gift offered to the Earth to give thanks for a healthy baby, and a carrier of a holographic imprint for the baby’s life on Earth. Most cultures bury the placenta (a few even give it funeral rites), some burn or eat it, and a few do lotus births (where the placenta stays attached to the baby until it dries out and falls off). The Hmong people in Laos believe a person’s spirit will wander the Earth and not be able to join their ancestors in the spirit world without returning to the place their placenta was buried and collecting it, and the word for placenta in their language translates as ‘jacket’ (

Placental ceremonies are based on traditional understandings of the placenta as a spiritual twin, a baby’s guardian angel, a ‘death’ gift offered to the Earth to give thanks for a healthy baby, and a carrier of a holographic imprint for the baby’s life on Earth. Most cultures bury the placenta (a few even give it funeral rites), some burn or eat it, and a few do lotus births (where the placenta stays attached to the baby until it dries out and falls off). The Hmong people in Laos believe a person’s spirit will wander the Earth and not be able to join their ancestors in the spirit world without returning to the place their placenta was buried and collecting it, and the word for placenta in their language translates as ‘jacket’ ( (Typical image of ‘spirituality’ from

(Typical image of ‘spirituality’ from  How do we know the difference between a spiritual experience and our imagination? I have seen a lot of people struggle with this – with their minds tricking them into thinking they have encountered a Spirit, for example. For me the difference is in embodiment. And when in doubt, see if and how changes occur in your everyday life as a result of the insight or guidance you got. (Image from

How do we know the difference between a spiritual experience and our imagination? I have seen a lot of people struggle with this – with their minds tricking them into thinking they have encountered a Spirit, for example. For me the difference is in embodiment. And when in doubt, see if and how changes occur in your everyday life as a result of the insight or guidance you got. (Image from

Initiations intentionally lead us through Earth’s cycle from life into death then rebirth with a new identity through a purposefully

Initiations intentionally lead us through Earth’s cycle from life into death then rebirth with a new identity through a purposefully  Initiations may be seen as having three distinct phases: separation (from daily reality), ordeal (trauma), and return (rebirth and resolution)

Initiations may be seen as having three distinct phases: separation (from daily reality), ordeal (trauma), and return (rebirth and resolution) One example of an ordeal is the Sateré-Mawé tradition of adolescent boys enduring the pain of repeatedly putting their hand into a glove filled with bullet ants that inject toxins into them

One example of an ordeal is the Sateré-Mawé tradition of adolescent boys enduring the pain of repeatedly putting their hand into a glove filled with bullet ants that inject toxins into them Initiations thus teach cultural myths and values, and ordeals without sacred spiritual stories attached to them are merely meaningless violence, reinforcing nihilism and lacking re-integration and fulfilment of a new identity along with its social responsibilities. In the example above, boys who complete the initiation are allowed to hunt and marry, which complete their rebirth as adult men in the community. Many of us grew up in cultures with rites of passage that included separation and ordeal phases but lacked full return phases to reintegrate us into a healthy new identity. We may feel called to question our

Initiations thus teach cultural myths and values, and ordeals without sacred spiritual stories attached to them are merely meaningless violence, reinforcing nihilism and lacking re-integration and fulfilment of a new identity along with its social responsibilities. In the example above, boys who complete the initiation are allowed to hunt and marry, which complete their rebirth as adult men in the community. Many of us grew up in cultures with rites of passage that included separation and ordeal phases but lacked full return phases to reintegrate us into a healthy new identity. We may feel called to question our  The dialogue of that name was with my friend

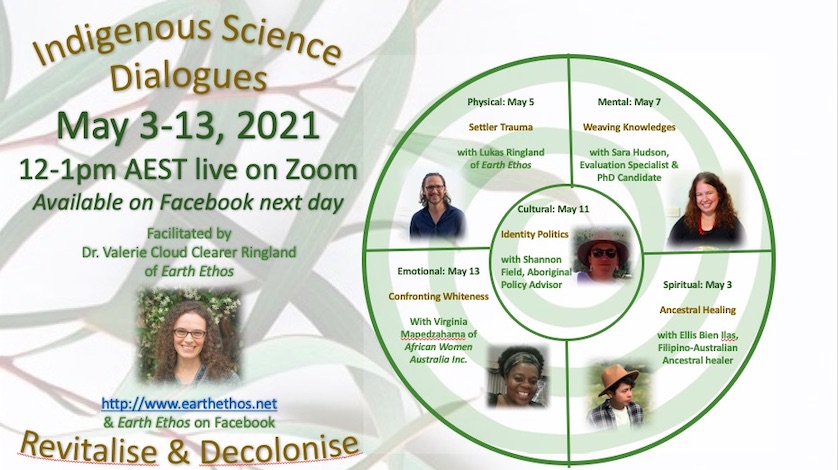

The dialogue of that name was with my friend

Shona (Zimbabwean) Australian woman

Shona (Zimbabwean) Australian woman  This “mere existence” of Aboriginal people as humans worthy of dignity collapses the entire ‘legal’ foundation of the Australian nation. The High Court overturned

This “mere existence” of Aboriginal people as humans worthy of dignity collapses the entire ‘legal’ foundation of the Australian nation. The High Court overturned  When I hear

When I hear