Blog by Valerie, following recent presentations with breastfeeding and pregnancy groups

We do ceremonies at important moments in our lives, such as weddings, graduations, and funerals. Ceremonies support us to gain knowledge, purify our spirits, and honour life. They can be as simple as a small act done with sacred intention, or as elaborate as a religious confirmation.

“In traditional practices and rituals, birthing involved more than the physical health of the mother and baby. Giving birth was a process of initiation and belonging to the culture that created spiritual links to the land and the ancestral Dreaming.”—Best, O., & Fredericks, B. (Eds.). (2021). Yatdjuligin: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander nursing and midwifery care. Cambridge University Press.

The birthing journey, from pregnancy to postpartum it is seen in Indigenous science as a time of spiritual initiation for the new mother. Initiations are transitional ceremonies that lead us through Earth’s cycle from life to death and rebirth into a new identity. For first time mothers, this journey is a profound shift from being a maiden into be-coming a mother, and for all mothers it is a journey of be-coming a mother within a new relationship.

Initiation ceremonies have three phases:

- Separation from daily reality;

- Ordeal or trauma; and

- Return or rebirth.

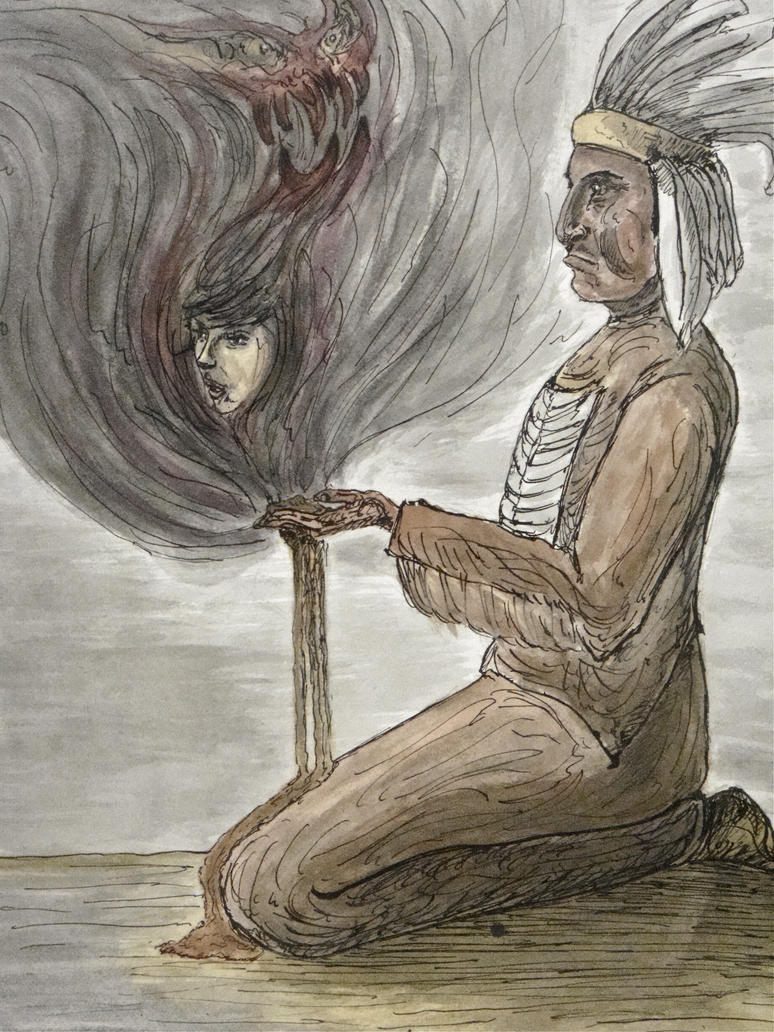

In an Indigenous worldview, the mother is seen as a conduit between the spiritual and physical worlds, and birthing trauma as a meaningful initiation into spiritual adulthood. In fact, many Indigenous cultures have initiation rites only for young men, because childbirth (as a birthing mother, through miscarriage, and/or through supporting birthing women) is considered to be the initiation process naturally built into women’s bodies. (Image: Natural Birth Art Print by Sean Frosali, Society6)

In an Indigenous worldview, the mother is seen as a conduit between the spiritual and physical worlds, and birthing trauma as a meaningful initiation into spiritual adulthood. In fact, many Indigenous cultures have initiation rites only for young men, because childbirth (as a birthing mother, through miscarriage, and/or through supporting birthing women) is considered to be the initiation process naturally built into women’s bodies. (Image: Natural Birth Art Print by Sean Frosali, Society6)

Phase 1: Separation from daily reality – being pregnant

The moment a woman is pregnant, she and everyone she meets is in ceremony…The womb is our first orientation on Earth.–Patricia Gonzalez, Red Medicine: Traditional Indigenous rites of birthing and healing

During pregnancy, traditional ceremonies are based on:

-

- Mothers and elders sharing wisdom about birthing, breastfeeding and childrearing;

- Cleansing the mother’s space, including her body and home (i.e. massage, smudging);

- Community support with certain tasks around the house for the mother;

- Taboos and norms about foods, drinks, and activities a mother ought to do or avoid;

- Honouring the babies’ soul entering the womb and protecting the mother and baby (i.e. with amulets, prayers, and rituals, and avoiding aspects of life such as funerals);

- Helping to welcome and support a new baby (i.e. to ease a first time mother’s anxiety, baby showers).

There are of course many cultural variations on such ceremonies. One example is in parts of India where there is a sort of baby shower called a Valaikaapu in which the mother-to-be is sung to by other women, adorned with bangles, soothed from anxiety with herbal treatment on her hands and feet, and fed traditional nourishing foods. After this ceremony in the third trimester, the mother-to-be traditionally stays at her parents’ house until the baby is born. Another example occurs in parts of Indonesia also begins in the third trimester with the mothers’ parents bringing food to their son-in-law’s family, and the mother ceremonially feeding her pregnant daughter before everyone else eats. The parents-to-be are then given blessings and encouragement by both the whole family, including being wrapped in traditional fabric as a symbol of strength for their union through the birthing journey (Silaban, I., & Sibarani, R. (2021). The tradition of Mambosuri Toba Batak traditional ceremony for a pregnant woman with seven months gestational age for women’s physical and mental health. Gaceta Sanitaria, 35, S558-S560.). (Image from here)

There are of course many cultural variations on such ceremonies. One example is in parts of India where there is a sort of baby shower called a Valaikaapu in which the mother-to-be is sung to by other women, adorned with bangles, soothed from anxiety with herbal treatment on her hands and feet, and fed traditional nourishing foods. After this ceremony in the third trimester, the mother-to-be traditionally stays at her parents’ house until the baby is born. Another example occurs in parts of Indonesia also begins in the third trimester with the mothers’ parents bringing food to their son-in-law’s family, and the mother ceremonially feeding her pregnant daughter before everyone else eats. The parents-to-be are then given blessings and encouragement by both the whole family, including being wrapped in traditional fabric as a symbol of strength for their union through the birthing journey (Silaban, I., & Sibarani, R. (2021). The tradition of Mambosuri Toba Batak traditional ceremony for a pregnant woman with seven months gestational age for women’s physical and mental health. Gaceta Sanitaria, 35, S558-S560.). (Image from here)

Phase 2: Trauma/ordeal – birthing

In the Mohawk language, one word for midwife…describes that “she’s pulling the baby out of the Earth,” out of the water, or a dark wet place. It is full of ecological context. We know from our traditional teachings that the waters of the earth and the waters of our bodies are the same.

—Rachel Olson, Indigenous Birth as Ceremony and a Human Right

During and immediately following birth, traditional ceremonies are based on:

-

- Birthing sites in sacred spaces indoors (e.g. sweat lodges) and outdoors (e.g. natural pools);

- Taboos about labour being quiet or loud, and women’s positions (e.g. squatting);

- Norms about partners being present at birth, or having their own tasks to do for the baby;

- Use of traditional herbal steams and poultices to cleanse the womb, stop bleeding, and help milk start flowing following the birth;

- Protecting the baby and mother;

- Umbilical cord ceremonial clamping and/or saving, or lotus birthing;

- Sensual imprinting for the newborn through wrapping them in traditional clothing, jewellery, fur, and/or blankets; and

- Body wrapping and womb re-warming practices for the mother after birth.

There are also many cultural variations for these ceremonies. For example, in Japan umbilical cords are saved and presented to new mothers in keepsake wooden boxes at hospitals. This tradition is meant to keep a good relationship between the mother and baby, and sometimes the box is given to the adult child when they leave home or marry to symbolise a separation in an adult-to-adult relationship. In Australian Aboriginal cultures, cultural birthing areas utilised natural depressions and sacred spaces such as rock formations, caves and water holes, to spiritually connect the child to their Country and their ancestors. Women followed ‘Grandmother’s Law’ which often included practices such as squatting over the steam of traditional medicinal plants after birth to prevent infection, how to name the child, and when the child would meet their father (Adams, K., Faulkhead, S., Standfield, R., & Atkinson, P. (2018). Challenging the colonisation of birth: Koori women’s birthing knowledge and practice. Women and Birth, 31(2), 81-88). (Image from here)

There are also many cultural variations for these ceremonies. For example, in Japan umbilical cords are saved and presented to new mothers in keepsake wooden boxes at hospitals. This tradition is meant to keep a good relationship between the mother and baby, and sometimes the box is given to the adult child when they leave home or marry to symbolise a separation in an adult-to-adult relationship. In Australian Aboriginal cultures, cultural birthing areas utilised natural depressions and sacred spaces such as rock formations, caves and water holes, to spiritually connect the child to their Country and their ancestors. Women followed ‘Grandmother’s Law’ which often included practices such as squatting over the steam of traditional medicinal plants after birth to prevent infection, how to name the child, and when the child would meet their father (Adams, K., Faulkhead, S., Standfield, R., & Atkinson, P. (2018). Challenging the colonisation of birth: Koori women’s birthing knowledge and practice. Women and Birth, 31(2), 81-88). (Image from here)

Phase 3: Return/rebirth – becoming a mother

We believe in waiting until 30 days after the birth for any celebrations. In our tradition, we believe that the unborn child has a guardian angel, who is the previous mother of the child. If we celebrate the pregnancy publicly, the spirit of the previous parent might come and reclaim her child — so that the new mother loses her baby!—Vietnamese grandmother quoted in Cusk, R. (2014). A Life’s Work. Faber & Faber.

In the postnatal months, traditional ceremonies are based on:

-

- Protecting the baby and mother;

- Naming and welcoming the baby to the land and family;

- Building the newborn’s resilience with elements and weather;

- “Firsts” (i.e. baths, foods, laughs, rolling over, walking, etc.);

- Mother’s rest and recovery from birth (often 40 days); and

- Placenta ceremonies.

A sweet example of such a ceremony comes from the Navajo/Diné people of North America have a ceremony to honour the babies’ first laugh, and the person who gets the baby to laugh throws a party where guests are given salt on the baby’s behalf as a symbol of generosity since it was traditionally valuable and hard to get (Brown, Shane. (2021). Why Navajos Celebrate the First Laugh of a Baby. https://navajotraditionalteachings.com/blogs/news/why-navajos-celebrate-the-first-laugh-of-a-baby). Across the world in Egypt, on the child’s seventh day after birth, a Sebou’ ceremony welcomes the baby with a number of traditions related to the cultural meaning of the number seven, such as placing the baby in a sieve and shaking them to symbolise life becoming more dynamic outside the womb, then stepping over them seven times saying prayers for protection and obedience to their parents; a candlelit procession of smudging the house; and a drink to increase breast milk production (Gamal, A. (2015). The Sebou‘: An Egyptian Baby Shower, https://www.madamasr.com/en/2015/11/02/panorama/u/the-sebou-an-egyptian-baby-shower/). And in Nordic countries, babies are traditionally left to nap outside no matter the weather to build their resilience to the earthly elements. Called friluftsliv it translates to ‘open-air life’ and represents cultural importance of enjoying nature and the outdoors all year round (McGurk, L. (2023). Creating a stronger family culture through ‘friluftsliv’, Children’s Nature Network, https://www.childrenandnature.org/resources/creating-a-stronger-family-culture-through-friluftsliv/). (Image by Joey Nash)

A sweet example of such a ceremony comes from the Navajo/Diné people of North America have a ceremony to honour the babies’ first laugh, and the person who gets the baby to laugh throws a party where guests are given salt on the baby’s behalf as a symbol of generosity since it was traditionally valuable and hard to get (Brown, Shane. (2021). Why Navajos Celebrate the First Laugh of a Baby. https://navajotraditionalteachings.com/blogs/news/why-navajos-celebrate-the-first-laugh-of-a-baby). Across the world in Egypt, on the child’s seventh day after birth, a Sebou’ ceremony welcomes the baby with a number of traditions related to the cultural meaning of the number seven, such as placing the baby in a sieve and shaking them to symbolise life becoming more dynamic outside the womb, then stepping over them seven times saying prayers for protection and obedience to their parents; a candlelit procession of smudging the house; and a drink to increase breast milk production (Gamal, A. (2015). The Sebou‘: An Egyptian Baby Shower, https://www.madamasr.com/en/2015/11/02/panorama/u/the-sebou-an-egyptian-baby-shower/). And in Nordic countries, babies are traditionally left to nap outside no matter the weather to build their resilience to the earthly elements. Called friluftsliv it translates to ‘open-air life’ and represents cultural importance of enjoying nature and the outdoors all year round (McGurk, L. (2023). Creating a stronger family culture through ‘friluftsliv’, Children’s Nature Network, https://www.childrenandnature.org/resources/creating-a-stronger-family-culture-through-friluftsliv/). (Image by Joey Nash)

Placental ceremonies are based on traditional understandings of the placenta as a spiritual twin, a baby’s guardian angel, a ‘death’ gift offered to the Earth to give thanks for a healthy baby, and a carrier of a holographic imprint for the baby’s life on Earth. Most cultures bury the placenta (a few even give it funeral rites), some burn or eat it, and a few do lotus births (where the placenta stays attached to the baby until it dries out and falls off). The Hmong people in Laos believe a person’s spirit will wander the Earth and not be able to join their ancestors in the spirit world without returning to the place their placenta was buried and collecting it, and the word for placenta in their language translates as ‘jacket’ (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hmong_women_and_childbirth_practices). In Maori language in New Zealand, ‘whenua’ is the word for both ‘land’ and ‘placenta’, and after childbirth the placenta is buried on ancestral lands to strengthen a child’s connection to culture, often beneath a tree (Soteria. (2020). Māoritanga: Pregnancy, Labour and Birth. https://soteria.co.nz/birth-preparation/maori-birthing-tikanga/). Placentas are dried and eaten to support the mothers’ or baby’s strength in many places, from China to Jamaica to Argentina (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Human_placentophagy).

Placental ceremonies are based on traditional understandings of the placenta as a spiritual twin, a baby’s guardian angel, a ‘death’ gift offered to the Earth to give thanks for a healthy baby, and a carrier of a holographic imprint for the baby’s life on Earth. Most cultures bury the placenta (a few even give it funeral rites), some burn or eat it, and a few do lotus births (where the placenta stays attached to the baby until it dries out and falls off). The Hmong people in Laos believe a person’s spirit will wander the Earth and not be able to join their ancestors in the spirit world without returning to the place their placenta was buried and collecting it, and the word for placenta in their language translates as ‘jacket’ (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hmong_women_and_childbirth_practices). In Maori language in New Zealand, ‘whenua’ is the word for both ‘land’ and ‘placenta’, and after childbirth the placenta is buried on ancestral lands to strengthen a child’s connection to culture, often beneath a tree (Soteria. (2020). Māoritanga: Pregnancy, Labour and Birth. https://soteria.co.nz/birth-preparation/maori-birthing-tikanga/). Placentas are dried and eaten to support the mothers’ or baby’s strength in many places, from China to Jamaica to Argentina (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Human_placentophagy).

Today, it might be hard to decide what to do if you don’t know your Indigenous roots and their cultural traditions, and when because many of us birth in hospitals. I suggest relying on your intuition, and what resonates with you. Some ceremonies common across cultures that you may wish to do for yourself and your baby may relate to:

-

- Prenatal blessings to keep the mother and baby safe;

- Connecting the baby to the land and elements (earth, air, fire, water);

- Postnatal rituals to keep the mother and baby safe;

- Placenta burial; and/or a

- Naming ritual.

Keep in mind that you can’t do a ceremony wrong if your heart and intention are in it. The way you feel during and after the ceremony will show you how it went. For my child, we did a prenatal baby shower/blessing with friends and family in person and on Zoom, and we printed out the blessings for our home-birthing space, then ultimately buried them with the placenta a few months after the birth. We chose our baby’s first sensual experiences – sight, smell, touch, and hearing, as her first taste was breastmilk! We brought earth inside to touch to her feet to connect her to the land as she was born in winter, and her placenta burial ceremony was on land where her great-great-great grandmother was buried.

I hope this has given you some things to reflect on and ideas for celebrating your journey into be-coming a mother in a way that feels sacred and special to you and your family. (Two other blogs you may find interesting about my birth and early mothering experiences are: about spirit babies, and mothering amidst intergenerational trauma).

If you value this content, please engage in reciprocity by living, sharing and giving.

If you value this content, please engage in reciprocity by living, sharing and giving.

![]() If you value this content, please engage in reciprocity by living, sharing and giving.

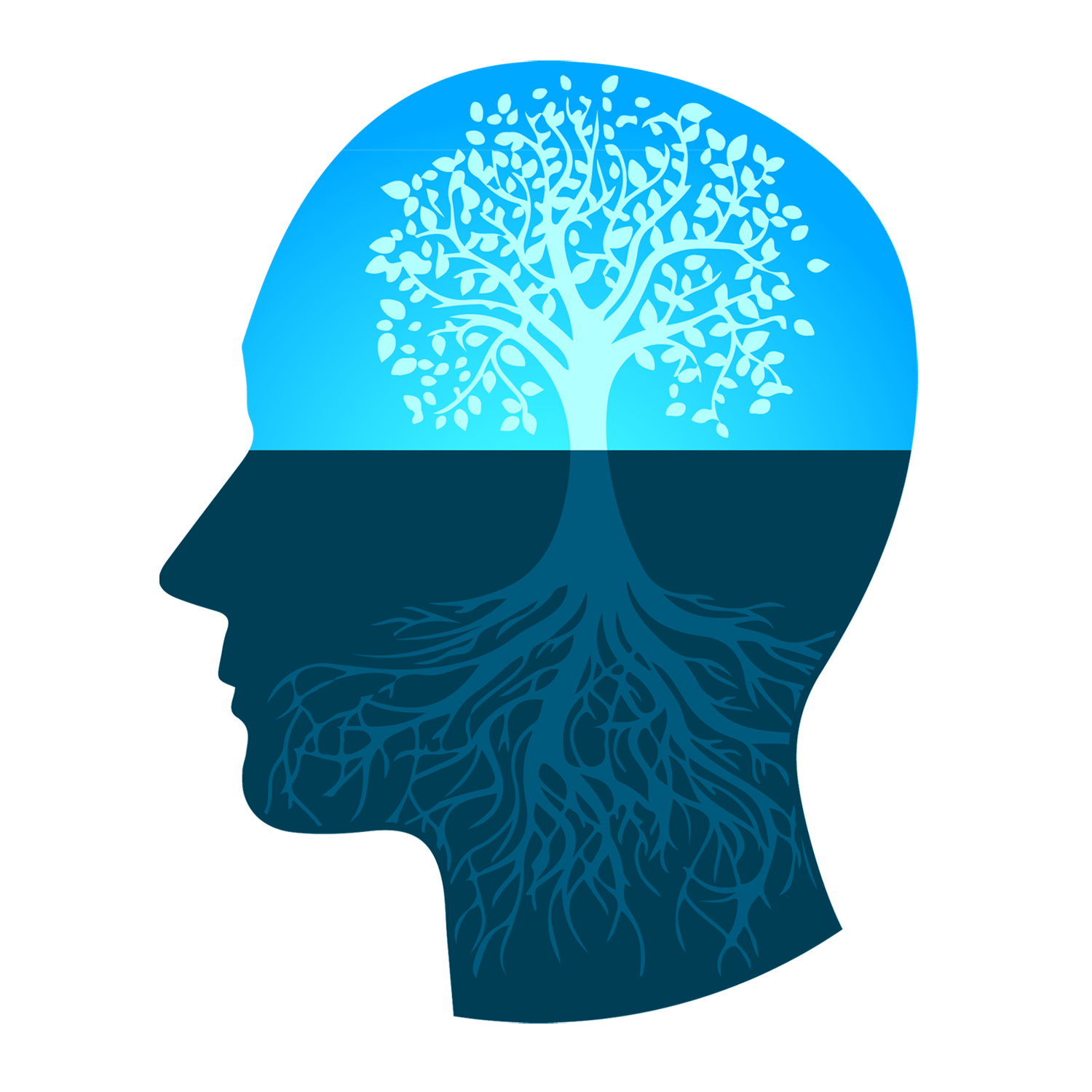

If you value this content, please engage in reciprocity by living, sharing and giving. For me it has been vital to live in two worlds: (1) a social reality that is based on a Western worldview, and (2) an earth-based reality based on an Indigenous worldview. When I’m caught up in a survival struggle in the Western world that’s terrifyingly real, and I’m feeling rejected and judged and shamed and angry, I can spiritually connect with the knowing from the Land and my ancestors that I’m not only allowed to exist but that I am wanted. This powerful medicine is all I have found that alleviates my existential wounds. Without it I feel like I would not still be here on this Earth, as my roots would have rotted and not been able to hold up the rest of my inner tree of life. (Image from

For me it has been vital to live in two worlds: (1) a social reality that is based on a Western worldview, and (2) an earth-based reality based on an Indigenous worldview. When I’m caught up in a survival struggle in the Western world that’s terrifyingly real, and I’m feeling rejected and judged and shamed and angry, I can spiritually connect with the knowing from the Land and my ancestors that I’m not only allowed to exist but that I am wanted. This powerful medicine is all I have found that alleviates my existential wounds. Without it I feel like I would not still be here on this Earth, as my roots would have rotted and not been able to hold up the rest of my inner tree of life. (Image from

Altering my consciousness is another survival tool I use daily, primarily through

Altering my consciousness is another survival tool I use daily, primarily through  In an Indigenous worldview, the mother is seen as a conduit between the spiritual and physical worlds, and birthing

In an Indigenous worldview, the mother is seen as a conduit between the spiritual and physical worlds, and birthing  There are of course many cultural variations on such ceremonies. One example is in parts of India where there is a sort of baby shower called a

There are of course many cultural variations on such ceremonies. One example is in parts of India where there is a sort of baby shower called a  There are also many cultural variations for these ceremonies. For example, in Japan

There are also many cultural variations for these ceremonies. For example, in Japan  A sweet example of such a ceremony comes from the Navajo/Diné people of North America have a ceremony to honour the babies’ first laugh, and the person who gets the baby to laugh throws a party where guests are given salt on the baby’s behalf as a symbol of generosity since it was traditionally valuable and hard to get (Brown, Shane. (2021). Why Navajos Celebrate the First Laugh of a Baby.

A sweet example of such a ceremony comes from the Navajo/Diné people of North America have a ceremony to honour the babies’ first laugh, and the person who gets the baby to laugh throws a party where guests are given salt on the baby’s behalf as a symbol of generosity since it was traditionally valuable and hard to get (Brown, Shane. (2021). Why Navajos Celebrate the First Laugh of a Baby.  Placental ceremonies are based on traditional understandings of the placenta as a spiritual twin, a baby’s guardian angel, a ‘death’ gift offered to the Earth to give thanks for a healthy baby, and a carrier of a holographic imprint for the baby’s life on Earth. Most cultures bury the placenta (a few even give it funeral rites), some burn or eat it, and a few do lotus births (where the placenta stays attached to the baby until it dries out and falls off). The Hmong people in Laos believe a person’s spirit will wander the Earth and not be able to join their ancestors in the spirit world without returning to the place their placenta was buried and collecting it, and the word for placenta in their language translates as ‘jacket’ (

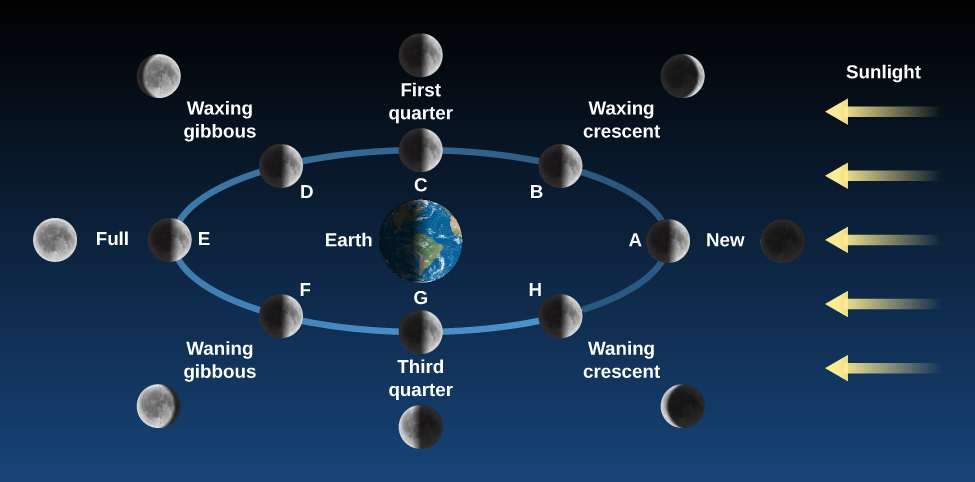

Placental ceremonies are based on traditional understandings of the placenta as a spiritual twin, a baby’s guardian angel, a ‘death’ gift offered to the Earth to give thanks for a healthy baby, and a carrier of a holographic imprint for the baby’s life on Earth. Most cultures bury the placenta (a few even give it funeral rites), some burn or eat it, and a few do lotus births (where the placenta stays attached to the baby until it dries out and falls off). The Hmong people in Laos believe a person’s spirit will wander the Earth and not be able to join their ancestors in the spirit world without returning to the place their placenta was buried and collecting it, and the word for placenta in their language translates as ‘jacket’ ( ‘We are cycles of time’ stuck in my head after reading a

‘We are cycles of time’ stuck in my head after reading a  So it’s fair to say that I have seen plenty of intergenerational trauma playing out in mine and other people’s lives. It’s particularly humbling to see it play out now, as a mother with my baby. But once I realize that’s what’s happening, I know we will have to ride this

So it’s fair to say that I have seen plenty of intergenerational trauma playing out in mine and other people’s lives. It’s particularly humbling to see it play out now, as a mother with my baby. But once I realize that’s what’s happening, I know we will have to ride this  I have felt a lot of grief that so much of my energy in the pregnancy and birth, and even as a young mother now, is about processing trauma and grief instead of just being in the moment enjoying my baby. Though I feel nervous about looking for housing, packing and moving, I realize we’re all a cycle in time. And though it’s tough, my role now is to process as much trauma and ground as much nervous energy as I can so my baby has more opportunity to be present with their child in the next cycle.

I have felt a lot of grief that so much of my energy in the pregnancy and birth, and even as a young mother now, is about processing trauma and grief instead of just being in the moment enjoying my baby. Though I feel nervous about looking for housing, packing and moving, I realize we’re all a cycle in time. And though it’s tough, my role now is to process as much trauma and ground as much nervous energy as I can so my baby has more opportunity to be present with their child in the next cycle. I bring this up because I find unconscious sorcery very common. I recently got to the root of a painful thought loop that’s informed my whole life and was quite surprised to find that it wasn’t intergenerational trauma as I expected, but in fact (I’m assuming unconscious) negative sorcery from a former big shot professor who had it in for my mother. I did hear stories growing up about how he had bullied her, like how when she was pregnant with me and asked for afternoon classes due to morning sickness, he gave her 8am classes instead. The belief he cursed me with was “you don’t belong here”. And I do feel it was directed at me, maybe even more than my mother, because he took great issue with a young mother having an academic career. And I made her into a mother.

I bring this up because I find unconscious sorcery very common. I recently got to the root of a painful thought loop that’s informed my whole life and was quite surprised to find that it wasn’t intergenerational trauma as I expected, but in fact (I’m assuming unconscious) negative sorcery from a former big shot professor who had it in for my mother. I did hear stories growing up about how he had bullied her, like how when she was pregnant with me and asked for afternoon classes due to morning sickness, he gave her 8am classes instead. The belief he cursed me with was “you don’t belong here”. And I do feel it was directed at me, maybe even more than my mother, because he took great issue with a young mother having an academic career. And I made her into a mother. That was his hook. But what about me? As

That was his hook. But what about me? As  So the next time you’re angry at a politician and notice yourself sending them daggered thoughts laced with negative emotion, or find yourself verbally ranting about them, stop and ask yourself how you’re using your power, and if you really intend to be cursing them. Cause what we do to others we invite into our own lives! And if you think you have been cursed, feel free to

So the next time you’re angry at a politician and notice yourself sending them daggered thoughts laced with negative emotion, or find yourself verbally ranting about them, stop and ask yourself how you’re using your power, and if you really intend to be cursing them. Cause what we do to others we invite into our own lives! And if you think you have been cursed, feel free to  There is so much power in

There is so much power in As an Indigenous scientist living far from ancestral lands, from a socio-political perspective, I am a settler

As an Indigenous scientist living far from ancestral lands, from a socio-political perspective, I am a settler Initiations intentionally lead us through Earth’s cycle from life into death then rebirth with a new identity through a purposefully

Initiations intentionally lead us through Earth’s cycle from life into death then rebirth with a new identity through a purposefully  Initiations may be seen as having three distinct phases: separation (from daily reality), ordeal (trauma), and return (rebirth and resolution)

Initiations may be seen as having three distinct phases: separation (from daily reality), ordeal (trauma), and return (rebirth and resolution) One example of an ordeal is the Sateré-Mawé tradition of adolescent boys enduring the pain of repeatedly putting their hand into a glove filled with bullet ants that inject toxins into them

One example of an ordeal is the Sateré-Mawé tradition of adolescent boys enduring the pain of repeatedly putting their hand into a glove filled with bullet ants that inject toxins into them Initiations thus teach cultural myths and values, and ordeals without sacred spiritual stories attached to them are merely meaningless violence, reinforcing nihilism and lacking re-integration and fulfilment of a new identity along with its social responsibilities. In the example above, boys who complete the initiation are allowed to hunt and marry, which complete their rebirth as adult men in the community. Many of us grew up in cultures with rites of passage that included separation and ordeal phases but lacked full return phases to reintegrate us into a healthy new identity. We may feel called to question our

Initiations thus teach cultural myths and values, and ordeals without sacred spiritual stories attached to them are merely meaningless violence, reinforcing nihilism and lacking re-integration and fulfilment of a new identity along with its social responsibilities. In the example above, boys who complete the initiation are allowed to hunt and marry, which complete their rebirth as adult men in the community. Many of us grew up in cultures with rites of passage that included separation and ordeal phases but lacked full return phases to reintegrate us into a healthy new identity. We may feel called to question our  Recently Lukas and I welcomed our daughter into this wild world. We won’t be posting any photos of her to protect her privacy, but here is one of us with her in my womb. More people are becoming familiar with the concept of a spirit baby (often through

Recently Lukas and I welcomed our daughter into this wild world. We won’t be posting any photos of her to protect her privacy, but here is one of us with her in my womb. More people are becoming familiar with the concept of a spirit baby (often through  And I got messages from her throughout the pregnancy; for example, I knew to

And I got messages from her throughout the pregnancy; for example, I knew to  Sometimes it’s tough to accept that the best gift we can give is to prevent the passing on of painful experiences and confused projections – and not by withholding or denying, which just buries the energy – but by expressing,

Sometimes it’s tough to accept that the best gift we can give is to prevent the passing on of painful experiences and confused projections – and not by withholding or denying, which just buries the energy – but by expressing,  Some years ago while working with practicing Jews and Christians, I realised the underlying process many of them were continually going through: judge an act as righteously right or wrong, confront moral failings within oneself and others, then forgive and let go by giving anger to God or Jesus. The depth of potential existential judgment is so intense (e.g. eternal damnation and social ostracisation), that it can be very hard for people to acknowledge ‘wrong’ behaviours. I have experienced numerous instances of trickery of someone intending to forgive and let go (or deciding to avoid an issue), resulting in hurtful and confusing passive-aggressive behaviours. Often the underlying issue emerges years later after so much resentment has built up and trust eroded that the relationship becomes very hard to repair. (Image from

Some years ago while working with practicing Jews and Christians, I realised the underlying process many of them were continually going through: judge an act as righteously right or wrong, confront moral failings within oneself and others, then forgive and let go by giving anger to God or Jesus. The depth of potential existential judgment is so intense (e.g. eternal damnation and social ostracisation), that it can be very hard for people to acknowledge ‘wrong’ behaviours. I have experienced numerous instances of trickery of someone intending to forgive and let go (or deciding to avoid an issue), resulting in hurtful and confusing passive-aggressive behaviours. Often the underlying issue emerges years later after so much resentment has built up and trust eroded that the relationship becomes very hard to repair. (Image from  Though it may at times seem more painful in the moment, I find loving acceptance brings me immeasurably more ease and peace than judging. I then discern what, if anything, I need to say or do when I experience hurt or realise I have caused hurt in another being. I remember Tom saying to me once that even when he doesn’t think he’s done anything wrong, if someone tells him that his actions have hurt them, he chooses to apologise because it is not his intention to hurt anyone. I appreciate the humility in that, and that it also helps hurting hearts to remain open to an ongoing relationship. (Image from

Though it may at times seem more painful in the moment, I find loving acceptance brings me immeasurably more ease and peace than judging. I then discern what, if anything, I need to say or do when I experience hurt or realise I have caused hurt in another being. I remember Tom saying to me once that even when he doesn’t think he’s done anything wrong, if someone tells him that his actions have hurt them, he chooses to apologise because it is not his intention to hurt anyone. I appreciate the humility in that, and that it also helps hurting hearts to remain open to an ongoing relationship. (Image from _-_Bette_and_Joan.png/250px-Feud_(Season_1)_-_Bette_and_Joan.png) Now that the Western justice system has criminalised the payback ceremony, many Aboriginal people in the Northern Territory struggle to reach forgiveness with their Indigenous science of justice. I heard about someone who had been in prison for years as ‘Western justice’ who was released and immediately had to face spearing if he wanted to see his family and community again. I heard about family members of an offender being beaten up until someone agreed to be speared in place of the offender in prison. I heard about decades-long violent feuds involving multiple generations where many people didn’t even know how the feud had started, but no one felt justice had been satisfied. I even heard about someone trying to sue someone else for using sorcery against their family as payback instead of spearing. It’s a mess. (Image from

Now that the Western justice system has criminalised the payback ceremony, many Aboriginal people in the Northern Territory struggle to reach forgiveness with their Indigenous science of justice. I heard about someone who had been in prison for years as ‘Western justice’ who was released and immediately had to face spearing if he wanted to see his family and community again. I heard about family members of an offender being beaten up until someone agreed to be speared in place of the offender in prison. I heard about decades-long violent feuds involving multiple generations where many people didn’t even know how the feud had started, but no one felt justice had been satisfied. I even heard about someone trying to sue someone else for using sorcery against their family as payback instead of spearing. It’s a mess. (Image from  Though we may not be able to ceremonially heal with the people who hurt us or people we have hurt, we can do spiritual ceremonies on our own to change the way we hold people and what we project. Shifting our perspective requires us to hold paradox and avoid binary and judgmental thinking. In traditional Hawaiian culture, people use “Ho’oponopono, the traditional conflict resolution process…[to] create a network between opposing viewpoints…that allows dualistic consciousness to stand while becoming fully embodied by the ecstatic love of Aloha”

Though we may not be able to ceremonially heal with the people who hurt us or people we have hurt, we can do spiritual ceremonies on our own to change the way we hold people and what we project. Shifting our perspective requires us to hold paradox and avoid binary and judgmental thinking. In traditional Hawaiian culture, people use “Ho’oponopono, the traditional conflict resolution process…[to] create a network between opposing viewpoints…that allows dualistic consciousness to stand while becoming fully embodied by the ecstatic love of Aloha”