Blog by Valerie

Some studies of newborns suggest that humans’ most fundamental need is to be part of a culture, to engage with their social environment and try to make sense of their surroundings. It can be helpful to conceptualise culture as a “cognitive orientation” instead of dividing people into racial or ethnic groups (Brubaker et. al, 2004), because “the most significant features of any child’s environment are the humans with whom they establish close relationships” who these days are often multi-cultural (Woodhead, 2005). Raising children is a process by which “we try to achieve cultural goals and well-being for ourselves and our children,” through pathways “determined by cultural activities organised into routines of everyday life” (Weisner, 1998). Children learn cultural models of living through relationships with parents, close kin and social institutions, during which time their young minds develop interdependently within their cultural context. This graphic shows elements of Yolgnu (Australia) child-rearing:

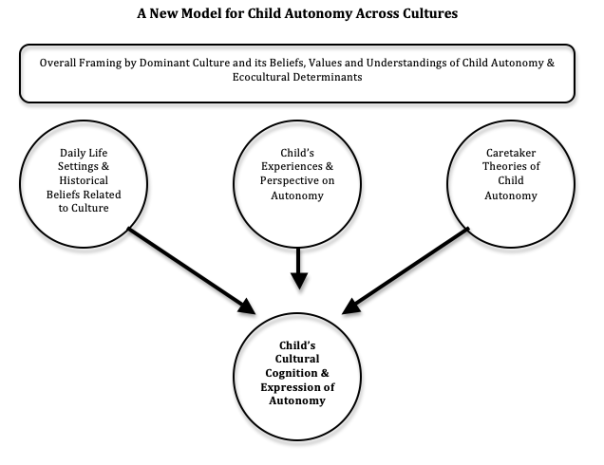

The developmental niche theory provides a framework for connecting culture with childrearing (Super & Harkness, 1994). A child’s physical and social settings, cultural customs of childcare, and psychology of caretakers form a “developmental niche”, and the eco-cultural niche theory identifies five areas of child development: (1) health and mortality; (2) food and shelter; (3) the people likely to be around children and what they are doing; (4) the role of women and mothers as primary caretakers; and (5) available alternatives to cultural norms (Harkness & Super, 1983). Some years ago I worked with social worker Amy Thompson to develop the following model:

In modern Western culture, there’s a lot that is broken, out of balance, and unwell. To intervene in any of the bubbles above will alter a child’s (or inner child’s) cultural identity and autonomy. And there’s a lot of wisdom in Indigenous childrearing.

Unlike the paternalistic culture many of us are familiar with, Earth Ethos parenting respects children’s agency. Autonomy is the freedom “to follow one’s own will” (Oxford English Dictionary). It’s important to note that autonomy is not the same as agency, or a child’s capacity for intentional, self-initiated behaviour. In “central Africa children are trained to be autonomous from infancy. They are taught to throw spears and fend for themselves. By age three they are expected to be able to feed themselves and subsist alone in a forest if need be” (quoted in Rogoff, 2003). Aka Pygmy children in Africa have access to the same resources as adults, whereas in the U.S. there are many adults-only resources that are off-limits to kids, and Among the Martu people of Western Australia, the worst offence is to impose on a child’s will, even if that child is only three years old” (Diamond, 2012). Yet Western children tend lack much autonomy and agency until they turn 18. One scholar suggests that four main ideas have shaped Western civilisation’s parenting practices:

- The young child is naturally wild and unregulated, and development is about socialising children to their place within society (e.g. Thomas Hobbes, 1588-1699);

- The young child is naturally innocent, development is fostered by protecting the innocence and providing freedom to play, learn and mature (e.g. Jacques Rousseau, 1712-1778);

- The young child is a ‘tabula rasa’ or blank slate, development is a critical time for laying the foundations that will enable children to reach their potential (e.g. John Locke, 1632-1704);

- The young child is shaped by nurture and nature, development is an interaction between potential and experience (e.g. Emmanuel Kant, 1724-1804) (Woodhead, 2005).

European American (mostly middle class) mothers have been extensively studied, and their parenting practices dominate popular culture and academic literature, yet a study across twelve countries found their beliefs and behaviours abnormal in an international context (Woodhead, 2005). Common conflicts between Western and other cultures were:

- Emphasis on the individual versus emphasis on the family;

- Autonomy versus interdependence;

- Youth culture versus respect for elders;

- Unisex versus gender differences;

- Individualism versus communal; and

- Competition versus cooperation (Friedman).

In most Indigenous cultures child development is not led by parents but is seen to naturally emerge through a network of kinship care. Children are seen as autonomous and encouraged to learn through experience rather than explicit instruction and rules (Sarche et. al, 2009). Parents avoid coercion and corporeal punishment, instead using storytelling and role modelling to discipline. This teaches natural consequences and allows parents to avoid imposing punishment. For example, this article shares a story of a preventive parenting practice by which an Inuit mother who asks her two-year-old son to throw rocks at her on the beach. He hits her leg, and she says, “Ow! That hurts!” to show him the consequence of hitting someone. And even if he kept throwing rocks after she showed the pain it caused, traditional Inuit still do not yell at children: “yelling at a small child [is seen] as demeaning. It’s as if the adult is having a tantrum; it’s basically stooping to the level of the child.” Child attachment differs from Western culture as well:

It isn’t just about attachment to the mother or the biological parents, but attachment to all of my relations. Practices and ceremonies were meant to build attachments to all parts of the community and the natural world, including the spirit world.–Kim Anderson, Métis (Canada)

An Anishinabe (Canada) woman explains the development of her attachment to Country through bush socialisation:

The absence of fences, neighbors and physical boundaries led way for the natural curiosities of a child to grow and be nurtured…I learnt to search for food, wood, plants, medicines and animals. Trees provided markers; streams, rivers and lakes marked boundaries, plants indicated location, and all this knowledge I developed out of just being in the bush…My bush socialization has taught me to be conscious of my surroundings, to be observant, to listen and discern my actions from what I see and hear. Elements of the earth, air, water and sun have taught me to be aware and move through the bush accordingly. (Image from here)

Ceremony is modelled from a young age. In this video, a Yolgnu (Australia) boy is barely walking and already learning traditional dances to connect with his community and his ancestors, and by the end of the video at age 7 is participating in a funeral dance:

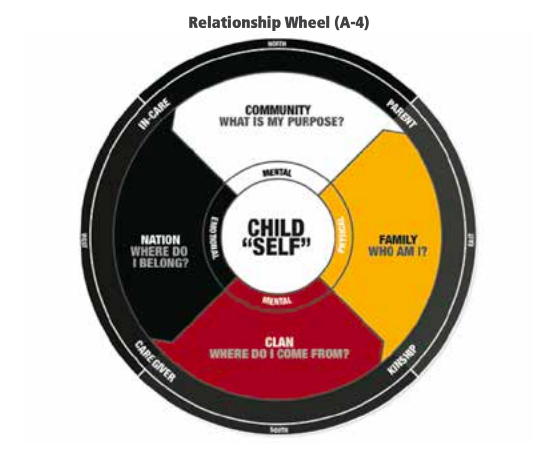

This medicine wheel from a childrearing manual for First Nations Canadians further demonstrates that in an Earth Ethos, children are seen as autonomous and interconnected, and shown how to live in balance with all my relations.

Exercise: What parenting perspective or childrearing practice would you like to improve in your life? Using suggestions from this post, researching on your own, or your own insight and intuition, what step could you take today to move further towards balance?

![]() If you value this content, please engage in reciprocity by living, sharing and giving.

If you value this content, please engage in reciprocity by living, sharing and giving.

I have a lot of compassion for the messiness of embodying Earth Ethos in modern multicultural cities. This is my life! And it is hard, messy work. It’s important to give ourselves and each other grace and trust that we all do our best. For a beautiful story from someone of mixed cultural heritage about honouring all of her complex heritage,

I have a lot of compassion for the messiness of embodying Earth Ethos in modern multicultural cities. This is my life! And it is hard, messy work. It’s important to give ourselves and each other grace and trust that we all do our best. For a beautiful story from someone of mixed cultural heritage about honouring all of her complex heritage,

A Druid

A Druid

Second, “if you don’t have an ancestor altar,

Second, “if you don’t have an ancestor altar,

(Image from

(Image from  Blog by Valerie

Blog by Valerie The depth of relationships, and the experiences, feel quite different to participants. Similarly, instead of peace circles as a tool to help control behaviour or improve the way people speak and listen to each other as is common in westernised restorative justice practices based on a Judeo-Christian worldview, an Earth Ethos peace circle is an opportunity for a communal spiritual experience based on an indigenous cultural cosmology. Because of the intentional use of metaphor, it ought to feel different to participants (and certainly does to me) than simply sitting in a circle (or around a table where we are blocked from connecting with each other physically) and passing around a talking piece. Many indigenous peoples use oral traditions to preserve cultural wisdom. Verbal repetition and physical embodiment of teachings keeps them pure (

The depth of relationships, and the experiences, feel quite different to participants. Similarly, instead of peace circles as a tool to help control behaviour or improve the way people speak and listen to each other as is common in westernised restorative justice practices based on a Judeo-Christian worldview, an Earth Ethos peace circle is an opportunity for a communal spiritual experience based on an indigenous cultural cosmology. Because of the intentional use of metaphor, it ought to feel different to participants (and certainly does to me) than simply sitting in a circle (or around a table where we are blocked from connecting with each other physically) and passing around a talking piece. Many indigenous peoples use oral traditions to preserve cultural wisdom. Verbal repetition and physical embodiment of teachings keeps them pure ( Healing of, and prevention of, dis-ease requires ceremony. Ceremony is an important human practice connecting the visible material/physical world with the invisible, spiritual world. Life feels empty and unsatisfying when we do not do enough ceremony, and ceremonies are most powerful done regularly and intentionally in community (

Healing of, and prevention of, dis-ease requires ceremony. Ceremony is an important human practice connecting the visible material/physical world with the invisible, spiritual world. Life feels empty and unsatisfying when we do not do enough ceremony, and ceremonies are most powerful done regularly and intentionally in community (

karma of humanity out. It’s all over the place: it’s conservative Christian parents confronting their prejudice with an LGBT child; a Southern Baptist who falls in love with a Catholic; a strong patriarch with a young daughter wiser than he is; a mother who worked so hard to break into the corporate world whose daughter wants to stay at home with her kids. Over and over again I see situations in which that which we judge, hate or reject is presented to us in an even more intimate way so that we learn to love and accept it. (Image from

karma of humanity out. It’s all over the place: it’s conservative Christian parents confronting their prejudice with an LGBT child; a Southern Baptist who falls in love with a Catholic; a strong patriarch with a young daughter wiser than he is; a mother who worked so hard to break into the corporate world whose daughter wants to stay at home with her kids. Over and over again I see situations in which that which we judge, hate or reject is presented to us in an even more intimate way so that we learn to love and accept it. (Image from  If you value this content, please engage in reciprocity by

If you value this content, please engage in reciprocity by  Americans often say, “I went for a walk in nature.” This is crazy, because we are always in nature. A house, a church, an office, a car—these are natural, highly cultivated, environments. A forest, a desert, a seashore, a mountaintop—these are natural, wilderness environments. Think about a spectrum of highly cultivated environments such as New York City, to total wilderness environments such as Alaska, and think about how you feel and behave in different environments. In cities, we tend to cultivate our lives: we carefully groom our faces, clothe our bodies, decorate our houses, cook pre-packaged foods, and schedule our time. In wilderness, we tend to let go and flow more. (Image from

Americans often say, “I went for a walk in nature.” This is crazy, because we are always in nature. A house, a church, an office, a car—these are natural, highly cultivated, environments. A forest, a desert, a seashore, a mountaintop—these are natural, wilderness environments. Think about a spectrum of highly cultivated environments such as New York City, to total wilderness environments such as Alaska, and think about how you feel and behave in different environments. In cities, we tend to cultivate our lives: we carefully groom our faces, clothe our bodies, decorate our houses, cook pre-packaged foods, and schedule our time. In wilderness, we tend to let go and flow more. (Image from

When we change our perspectives, we change the world. When we recognise value in plants and animals in our environments, we act accordingly. Ten years ago few of us knew what “free range”, “grass fed” or “organic” food was. As an increasing number of people saw the destructive impacts of pesticides and other high-yield agricultural practices, collective modern culture began to change. Today, most of us are more aware of what we’re eating than we were ten or twenty years ago. That gives me hope that as we keep growing, more Earth Ethos changes will occur in our lifetimes. (Image from

When we change our perspectives, we change the world. When we recognise value in plants and animals in our environments, we act accordingly. Ten years ago few of us knew what “free range”, “grass fed” or “organic” food was. As an increasing number of people saw the destructive impacts of pesticides and other high-yield agricultural practices, collective modern culture began to change. Today, most of us are more aware of what we’re eating than we were ten or twenty years ago. That gives me hope that as we keep growing, more Earth Ethos changes will occur in our lifetimes. (Image from