This blog builds on part 1 from a few weeks ago, which started by reminding you that in animism, it’s not only not expected, but against our own nature to play nice with certain beings and energies. Earlier today I heard the following story:

Three cyclists were riding down a neighbourhood road when an older guy in sports car drove by and yelled, “Get off the road, assholes!”. Of course, cyclists are legally allowed to be on the road. The female in the group gave him the middle finger, angering the driver more and he turned his car towards her, then veered onto another street and into a carpark of a private club. She almost fell off her bike, scared and filled with rage. She blasted through the private club gate past the security guard while her fellow cyclists followed and called the police. You might be thinking that she was trying to get the driver’s plates, but she already got a photo of that. When he stepped out of his car she screamed in his face how wrong his actions were and how terrified she felt. He pushed her out of his way, and she raged even more and threatened to press charges for touching her. By this time her companions had gotten through the security gate. The security guard initially threatened to call the police and report the cyclists for trespass, but changed his mind when he saw the scene. Police arrived and explained to the driver that cyclists are allowed on the roads as much as he is, and told the cyclists they can’t charge the driver with anything but simple battery for pushing her because he veered his car away and didn’t hurt anyone. No one was happy with this outcome.

Three cyclists were riding down a neighbourhood road when an older guy in sports car drove by and yelled, “Get off the road, assholes!”. Of course, cyclists are legally allowed to be on the road. The female in the group gave him the middle finger, angering the driver more and he turned his car towards her, then veered onto another street and into a carpark of a private club. She almost fell off her bike, scared and filled with rage. She blasted through the private club gate past the security guard while her fellow cyclists followed and called the police. You might be thinking that she was trying to get the driver’s plates, but she already got a photo of that. When he stepped out of his car she screamed in his face how wrong his actions were and how terrified she felt. He pushed her out of his way, and she raged even more and threatened to press charges for touching her. By this time her companions had gotten through the security gate. The security guard initially threatened to call the police and report the cyclists for trespass, but changed his mind when he saw the scene. Police arrived and explained to the driver that cyclists are allowed on the roads as much as he is, and told the cyclists they can’t charge the driver with anything but simple battery for pushing her because he veered his car away and didn’t hurt anyone. No one was happy with this outcome.

What a mess. Something to keep in mind with animism, and indigenous understandings of justice in general, is that they don’t necessarily align with Judeo-Christian morality. This may be the heart of why so often people feel things that happen are unfair or that ‘nice guys finish last’, because we are mentally programmed to expect rewards when we are ‘good’, whatever that means (often obedience to social norms it seems).

Five basic approaches to conflict resolution are: collaborating, compromising, accomodating, avoiding, and competing. In the story above, the woman and the driver are both competing. I  think about a lion competing to be king of the hill – they’re getting their fight on.

think about a lion competing to be king of the hill – they’re getting their fight on.  The security guard started out competing but then accommodated the cyclists, represented by a chameleon changing its colours to fit the situation. The other two cyclists are collaborating with their friend, like a school of fish sticking together, and the police officer is

The security guard started out competing but then accommodated the cyclists, represented by a chameleon changing its colours to fit the situation. The other two cyclists are collaborating with their friend, like a school of fish sticking together, and the police officer is  compromising by offering to charge the driver with something since the cyclists want him to be punished. Compromise is represented well by a zebra with its dual-coloured stripes.

compromising by offering to charge the driver with something since the cyclists want him to be punished. Compromise is represented well by a zebra with its dual-coloured stripes.

What we don’t have in this scenario is anyone avoiding conflict, which I think would have been the wisest option. There were many missed opportunities for the cyclists to avoid escalating the conflict and potentially endangering themselves further. Let’s represent avoiding with a turtle who can stick its head in its shell.

If the cyclists had been growled at by an actual lion, they likely would not have tried to compete but would have done their best to avoid escalating the conflict. And if one of the cyclists had decided to angrily provoke the lion further, the other cyclists would have been less likely to collaborate and more likely if she got hurt to tell her that she had asked for it. Other than a sense of moral outrage and upholding of social norms, why do we behave so differently with people who exhibit threatening lion energy than with actual lions? One reason is when something is really important to us, we feel called to be warriors and stand up and fight. Some things – like protecting our family – feel worth dying for, and it can be too hard to live with the guilt and shame of knowing we didn’t try to stand up for our values. Another reason is that we are reacting in autopilot and have a tendency to compete when we feel threatened. If the reason is the latter, we can work on creating self-awareness and space to make more intentional decisions about addressing conflicts.

When we do choose to avoid a conflict, it helps to be aware of the Cycle of Indecision: ‘I feel bad. I should do something. Nothing will change. I gotta let it go. But I feel bad…’ I find when I avoid a conflict but over time it keeps coming up inside me, then I do need to do something to address it. That may involve talking to someone, creating art to express my emotions and tell my story, doing something ceremonial to keep the energy flowing without endangering myself, or finding a passion to advocate out in the world. For example, if I have a conflict with someone close to me, I tend to try to collaborate and talk it through when we are both less emotionally charged. But when I have a conflict with someone I don’t trust to collaborate with, I often write them a letter, leave it on my altar, and burn it so that the energy gets sent out in spirit.

When we do choose to avoid a conflict, it helps to be aware of the Cycle of Indecision: ‘I feel bad. I should do something. Nothing will change. I gotta let it go. But I feel bad…’ I find when I avoid a conflict but over time it keeps coming up inside me, then I do need to do something to address it. That may involve talking to someone, creating art to express my emotions and tell my story, doing something ceremonial to keep the energy flowing without endangering myself, or finding a passion to advocate out in the world. For example, if I have a conflict with someone close to me, I tend to try to collaborate and talk it through when we are both less emotionally charged. But when I have a conflict with someone I don’t trust to collaborate with, I often write them a letter, leave it on my altar, and burn it so that the energy gets sent out in spirit.

Notice that no one in the story above was happy with what the police officer offered as a compromise to try to appease everyone and follow the law he’s working with. This is because of a common conflict resolution issue – people conflating positions with interests. The cyclists’ interests are (likely) being safe and respected while on the road, but their position is they want the driver to be punished for yelling at them and veering his car at the woman, but they may also have an interest in revenge.  The driver’s interest is (likely) not being criminally charged and being able to express anger that cyclists are not riding single file (which they don’t have to). Maybe he has an interest in trying to change that law or have cycling lanes built on the road so he doesn’t have to share, or maybe he’s just interested in expressing anger, but his position seems to be ‘get out of my way’. We’d need to talk to everyone to unpack their underlying interests and potentially resolve the conflict in a more mutually beneficial way, but that’s not the job of the police officer. That’s something we could do through an Earth Ethos peace circle if everyone was open to collaborating and had been prepared to come together with open hearts and minds. In peace circle processes we use deep listening, open questions, I-statements, reframing emotionally charged language, and other tools to make it easier for people in competitive positions to feel safe to open up and connect with others. Because lions tend to be lonely, dangerous creatures – with only one male on top of the pride, he’s always scared of being bested by another and losing everything. Sometimes conflicts in our lives are like that, are all or nothing, but usually they needn’t be. We just can’t see another way. (Image from here.)

The driver’s interest is (likely) not being criminally charged and being able to express anger that cyclists are not riding single file (which they don’t have to). Maybe he has an interest in trying to change that law or have cycling lanes built on the road so he doesn’t have to share, or maybe he’s just interested in expressing anger, but his position seems to be ‘get out of my way’. We’d need to talk to everyone to unpack their underlying interests and potentially resolve the conflict in a more mutually beneficial way, but that’s not the job of the police officer. That’s something we could do through an Earth Ethos peace circle if everyone was open to collaborating and had been prepared to come together with open hearts and minds. In peace circle processes we use deep listening, open questions, I-statements, reframing emotionally charged language, and other tools to make it easier for people in competitive positions to feel safe to open up and connect with others. Because lions tend to be lonely, dangerous creatures – with only one male on top of the pride, he’s always scared of being bested by another and losing everything. Sometimes conflicts in our lives are like that, are all or nothing, but usually they needn’t be. We just can’t see another way. (Image from here.)

Exercise: Reflect on how you tend to approach conflicts. Maybe you tend towards different approaches at home or at work or with your kids or partner. Think about a recent conflict you were in with someone. How did you want to approach that conflict? What was your position in the conflict, and your underlying interest(s)? What about the person you were in conflict with?

![]() If you value this content, please engage in reciprocity by living, sharing and giving.

If you value this content, please engage in reciprocity by living, sharing and giving.

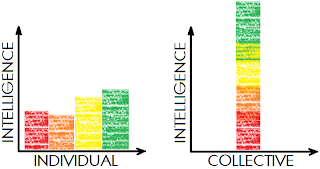

In social environments, it seems to feel proportionally less safe to be oneself the farther we identify from collective norms and ideals. There is a concept in mathematics called ‘regression to the mean’. It is basically the idea that when you put some ice into a glass of water, the ice will tend to melt and take the form of the water; in essence, it is about assimilating into a collective norm. Yet assimilation is a dirty word for many people, because we want to celebrate our uniqueness as well as being part of a peoples. (Image from

In social environments, it seems to feel proportionally less safe to be oneself the farther we identify from collective norms and ideals. There is a concept in mathematics called ‘regression to the mean’. It is basically the idea that when you put some ice into a glass of water, the ice will tend to melt and take the form of the water; in essence, it is about assimilating into a collective norm. Yet assimilation is a dirty word for many people, because we want to celebrate our uniqueness as well as being part of a peoples. (Image from  Feeling safe to celebrate our difference depends on culture and context. These social wounds keep us trapped and unable to trust ourselves, each other, non-humans, and Spirit/God/oneness. Our capacities to heal and seek retribution are also based on cultural values and intergenerational traumas. Cultures that are more welcoming of outsiders seem to encourage healing and embracing collective wounds for transformation, whereas cultures that are more exclusionary seem to ‘other’ people and tend towards separation and seeking retribution. Fear of retribution can keep us trapped and unable to trust. It is as if there is a collective trauma belief that says, ‘if we let them in, they will hurt us.’ In my experience with Judaism, and what I am learning are my deeper Sumerian cultural roots, there seems to be a collective belief that ‘we can’t trust anybody.’ My own grandmother told me that as a child, and I asked her incredulously if I couldn’t even trust her. She didn’t answer, just stared at me in silence. Living in this social environment, I never felt safe. In fact, I felt terrified to even take up space. One wrong move could find me terribly punished, kicked out of the group, or worse, judged irredeemable by God. Despite constantly striving to be ‘a good person’, it never felt like what I did was good enough. I got used to feeling terrified that threats of judgment, punishment and retribution were always imminent. I worked hard to learn the rules I might break and the triggers I might set off that would result in my being punished. But I wasn’t in control. My brother had a habit of breaking rules and refusing to admit it, so we would both be punished. This was scary, too, because I didn’t know when the punishment would happen, or how intense it would. It felt safer at times to intensely control and punish myself so that I maintained a sense of autonomy. It also seemed safest to play the part of

Feeling safe to celebrate our difference depends on culture and context. These social wounds keep us trapped and unable to trust ourselves, each other, non-humans, and Spirit/God/oneness. Our capacities to heal and seek retribution are also based on cultural values and intergenerational traumas. Cultures that are more welcoming of outsiders seem to encourage healing and embracing collective wounds for transformation, whereas cultures that are more exclusionary seem to ‘other’ people and tend towards separation and seeking retribution. Fear of retribution can keep us trapped and unable to trust. It is as if there is a collective trauma belief that says, ‘if we let them in, they will hurt us.’ In my experience with Judaism, and what I am learning are my deeper Sumerian cultural roots, there seems to be a collective belief that ‘we can’t trust anybody.’ My own grandmother told me that as a child, and I asked her incredulously if I couldn’t even trust her. She didn’t answer, just stared at me in silence. Living in this social environment, I never felt safe. In fact, I felt terrified to even take up space. One wrong move could find me terribly punished, kicked out of the group, or worse, judged irredeemable by God. Despite constantly striving to be ‘a good person’, it never felt like what I did was good enough. I got used to feeling terrified that threats of judgment, punishment and retribution were always imminent. I worked hard to learn the rules I might break and the triggers I might set off that would result in my being punished. But I wasn’t in control. My brother had a habit of breaking rules and refusing to admit it, so we would both be punished. This was scary, too, because I didn’t know when the punishment would happen, or how intense it would. It felt safer at times to intensely control and punish myself so that I maintained a sense of autonomy. It also seemed safest to play the part of  For most of my life I felt terrified to take up space. I felt like no space was ‘mine’ existentially or practically. For example, growing up, I wasn’t allowed to lock my bedroom door. I used to get dressed in my walk-in closet so I had some privacy and warning if my mother was coming into my bedroom. It took many years into adulthood – and practically ending many formational familial relationships that were untrustworthy just as my grandmother had told me – for me to become trustworthy to myself, be authentic and celebrate my difference, and surround myself with trustworthy and authentic people. By trustworthy, I mean people who say what they mean and do what they say, and when they can’t follow through on something, own it, apologise, forgive themselves, and make amends if needed. By authentic, I mean people who know their core values and practice embodying them in everyday life.

For most of my life I felt terrified to take up space. I felt like no space was ‘mine’ existentially or practically. For example, growing up, I wasn’t allowed to lock my bedroom door. I used to get dressed in my walk-in closet so I had some privacy and warning if my mother was coming into my bedroom. It took many years into adulthood – and practically ending many formational familial relationships that were untrustworthy just as my grandmother had told me – for me to become trustworthy to myself, be authentic and celebrate my difference, and surround myself with trustworthy and authentic people. By trustworthy, I mean people who say what they mean and do what they say, and when they can’t follow through on something, own it, apologise, forgive themselves, and make amends if needed. By authentic, I mean people who know their core values and practice embodying them in everyday life. It is still unsafe for me in many spaces where my values conflict with the collective. But I don’t feel a need to constantly strive towards some central ideal, nor do I feel like it’s me against the world at war. I feel peace in myself for accepting who I am and doing my best to navigate the collective morass, and for cultivating spaces where I, and others, are free to be. In this way, I can embody the knowing that we are enough. (Or ‘good enough’, whatever that means.) (Image from

It is still unsafe for me in many spaces where my values conflict with the collective. But I don’t feel a need to constantly strive towards some central ideal, nor do I feel like it’s me against the world at war. I feel peace in myself for accepting who I am and doing my best to navigate the collective morass, and for cultivating spaces where I, and others, are free to be. In this way, I can embody the knowing that we are enough. (Or ‘good enough’, whatever that means.) (Image from

In this section of Mary Shutan’s Body Deva book, she has an exercise called

In this section of Mary Shutan’s Body Deva book, she has an exercise called

This is the person with the most social power, both within their group and across groups. The Ringleader commonly lacks classic “excuses” for their behaviour, and usually comes from a relatively “

This is the person with the most social power, both within their group and across groups. The Ringleader commonly lacks classic “excuses” for their behaviour, and usually comes from a relatively “ The Henchmen are the bane of any true bullying victim’s life, dishing out most of the torment at the behest or with the support of the Ringleader. They are often quite dissociated emotionally and act without shame, which is both part of their resilience, and what makes them very dangerous.

The Henchmen are the bane of any true bullying victim’s life, dishing out most of the torment at the behest or with the support of the Ringleader. They are often quite dissociated emotionally and act without shame, which is both part of their resilience, and what makes them very dangerous.

I have heard people of many cultures say the world we’re living in was created by trickster. Some cultural creation stories are explicit about this, such as

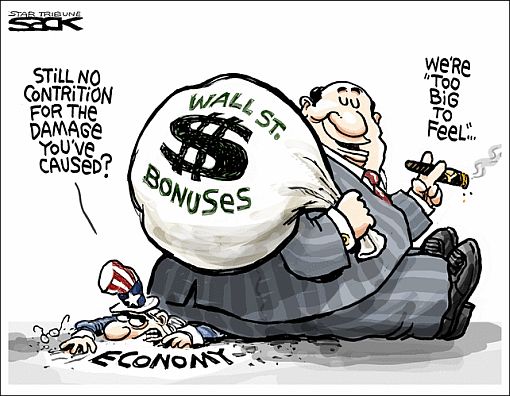

I have heard people of many cultures say the world we’re living in was created by trickster. Some cultural creation stories are explicit about this, such as  My view is that we’re all somewhat tricked into thinking that the collective ways we’re living are working, when deep down we feel pain, grief, conflict, helplessness, etc. about changing. We may be aware that current systems and ways of being and acting are unsustainable, and we may already be taking active steps to change ourselves and to advocate for bigger visions of change. Individual action does matter, miracles do occur, and self discipline and personal perseverance only takes us so far. As Isaac Murdoch, an Anishinaabeg elder (Canada)

My view is that we’re all somewhat tricked into thinking that the collective ways we’re living are working, when deep down we feel pain, grief, conflict, helplessness, etc. about changing. We may be aware that current systems and ways of being and acting are unsustainable, and we may already be taking active steps to change ourselves and to advocate for bigger visions of change. Individual action does matter, miracles do occur, and self discipline and personal perseverance only takes us so far. As Isaac Murdoch, an Anishinaabeg elder (Canada)

Another famous idea is the “

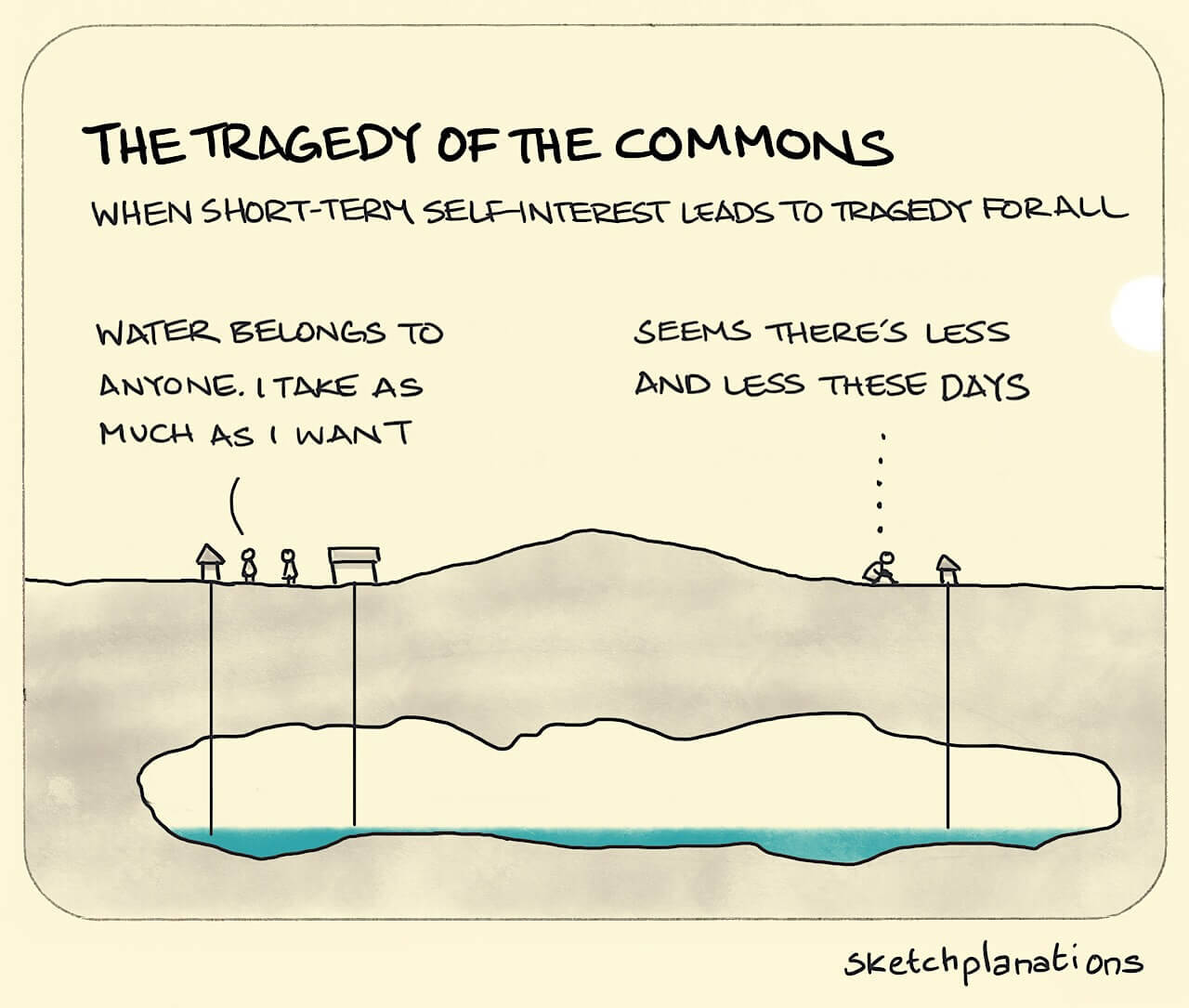

Another famous idea is the “ A third framework of interest, and perhaps most relevant to our toilet paper dilemma, is the idea of

A third framework of interest, and perhaps most relevant to our toilet paper dilemma, is the idea of  Looking at these articles on Wikipedia, it struck me how much that I think ought be deeply ingrained wisdom and self-evident knowledge has been studied intellectually and quantified as ‘evidence’. This is borne out by people acting like they need this kind authoritative guidance and advice before believing something is true. For example, the Tragedy of the Commons article mentions a

Looking at these articles on Wikipedia, it struck me how much that I think ought be deeply ingrained wisdom and self-evident knowledge has been studied intellectually and quantified as ‘evidence’. This is borne out by people acting like they need this kind authoritative guidance and advice before believing something is true. For example, the Tragedy of the Commons article mentions a